I am a criminal. More precisely, I am the kind of criminal that Charles Murray likes. Now, as is well-known, everyone is a criminal nowadays, because of the enormous expansion of deliberately vague and open-ended criminal laws. The average American commits multiple federal felonies every day. But Charles Murray specifically wants every American to commit a precise type of relatively limited crime, and I realize with joy that I have been happy to oblige his request for several years.

I am a criminal. More precisely, I am the kind of criminal that Charles Murray likes. Now, as is well-known, everyone is a criminal nowadays, because of the enormous expansion of deliberately vague and open-ended criminal laws. The average American commits multiple federal felonies every day. But Charles Murray specifically wants every American to commit a precise type of relatively limited crime, and I realize with joy that I have been happy to oblige his request for several years.

My crime (doubtless among others I am unaware of) is that I own and run a business (itself suspicious in these days of “you didn’t build that”), and for years the United States Department of Commerce has sent me questionnaires, prominently stamped “Response Required By Law.” These questionnaires arrive every month or so, and they are voluminous and intrusive. They demand I answer questions about my customers, my sales, my profit, my employees, and so forth. I throw them in the trash, unopened, and laugh bitterly at the toxic nature of the federal government.

Charles Murray says we should all break the law this way, and we should all similarly violate a wide range of similarly disgusting, undemocratic and anti-freedom regulations imposed on us by our federal masters. From this, aided by entities that will support such lawbreakers, a revitalized America may arise.

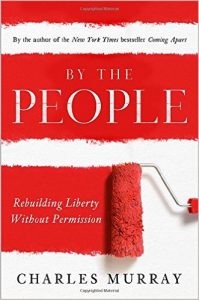

Murray is a libertarian writer on numerous topics, and he is an excellent and compelling author. He first takes the reader on a tour through where America started, how we got the administrative governance system we have today, why that system is defective, and why our existing political process will never fix it. Much of this is familiar territory, but very well drawn.

Murray’s particular focus is the administrative state, the false premises on which its creation was based, and its current illegitimacy. He traces its development down through nearly the present day (although he writes before the 2015 Obamacare decision, King v. Burwell, which intimated the possibility that the Supreme Court might be willing to cut back on Chevron deference), and shows compellingly that no normal process will reverse the evils that it has visited upon America.

Summarizing our problems and how we got here naturally leads to profound pessimism, especially given that Murray, who is an optimist, concludes that no normal mechanism will fix things. This is usually the point at which people start muttering about the need for a Caesar, a revolution, or the aptly named Sweet Meteor Of Doom. But Murray wants us to head in a different direction.

He wants civil disobedience, coupled with a program of defense of those committing civil disobedience, to erode the foundations of the modern oppressive regulatory state. Actually, Murray’s plan would better be described not as civil disobedience as traditionally understood, but as conservative lawfare generated by civil disobedience. The Left, of course, has been very successful at using the courts as mechanisms to attack, dismay and bankrupt their opponents. When your goal is not justice but winning, and you are extremely well-funded and can coordinate legal attacks with sympathetic government agencies and a media wholly rooting for you, that is a very successful tactic. Murray wants rich conservatives to fund a similar program for the right, from the springboard of individual civil disobedience.

The problem with this is, of course, there’s a long way from here to there. Rich conservatives are rare—they are a surprisingly small group. Most of the ultra-rich are closely aligned with the Left, and most who aren’t are politically uninvolved. None seem to give significantly to existing similar conservative organizations, such as the Pacific Legal Foundation. But more importantly, the courts, the government, and the media would not be neutral—they would retaliate viciously against any of these tactics being used by conservatives as they have been by liberals, not only trying to blunt them but ruining any person who led, both financially and likely with multi-decade jail sentences using the same vague and open-ended laws of which Murray complains. The fundamental problem with Murray’s approach is that it assumes, without discussion, that the Left will subject themselves to the rules. In the modern era of Alinskyite domination, rules are only for the little people, and power is all that matters.

But Murray soldiers on with optimism. He concedes that the administrative state at inception had some value and some sound reasoning behind it (though its modern grotesque nature has shown the falsity of the premises and released the evil genie within), but then he gives reasons why he thinks the administrative state is not at all necessary today, if elements of it were necessary in the past. In essence this is because technology enables public, decentralized oversight—the Nirvana of the libertarian. This is an original approach to the problem, certainly.

And, ultimately, Murray believes that no matter what, 200 years from now America will be much richer, because we’ve always grown in the past, and “it is unimaginable that Americans will still think the best way to live is to be governed by armies of bureaucrats enforcing thousands of minutely prescriptive rules.” This is a bit Pollyana-ish—as the law makes sellers of securities say, past performance is no indication of future results. Maybe we’ll just stagnate for 200 years. Certainly that’s where we’re heading now.

The most original part of the book is not the call for civil disobedience or lawfare. It’s that Murray tries to demonstrate that America is ready for a more libertarian, more individual way of life, because modern America is diverse in a way that pre-1950s America was diverse. He discusses “Albion’s Seed” at length, on the huge cultural divergences among Britons who populated America, together with many other groups and peoples in years after that. That is, he maintains that the perceived past homogeneity of America is a myth, and as in the past we should be able to recognize and honor our differences by getting the government off our backs. Everyone should be able to “live his life as he sees fit,” and our return to historical diversity, Murray thinks, will make this more attractive. (Here, “diversity” means actual differences among people, not “diversity” in the more common modern and academic sense of handing over free goods to unqualified minorities. Murray’s diversity does not erode excellence, like modern “diversity”—it enhances excellence.) Murray believes that the diverse elements of modern America can get together behind his program. Given that Murray is both a sociologist and a libertarian, this analysis is clearly close to his heart.

Of course, that past diversity contained within it certain universally held concepts, among them individual responsibility and the melting pot, that have largely passed into memory. Mere past and present diversity does not necessarily imply similarity in vision of the common good, and large segments of the Left exalt the centrifugal aspects of cultural diversity, an entirely new phenomenon on our country. So here as well, Murray is probably too cheerful about the prospects for the future.

Ultimately, the success of Murray’s program relies on a groundswell from a majority of Americans, tired of the costs of government and become eager to free themselves of its yoke. But it’s not true that most Americans feel like government is the problem. As with taxes, the costs of government appear to be borne by a small percentage of people. Yes, they’re really borne by a majority of people, but that’s hidden and lost in the shuffle. Most people don’t care. They’re happy they’re getting theirs. Therefore, somewhat ironically, Murray’s program is probably better suited for imposition by an oligarchical elite, not a renewed spirit of American populism.