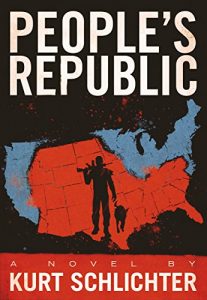

“People’s Republic” is part satire, part warning and part what I would call “conservative military revenge fantasy.” It’s a well-written, gripping read (like everything Schlichter writes). And the combination is successful, if the goal is to hold the reader’s interest and offer a frisson of conservative thrills.

“People’s Republic” is part satire, part warning and part what I would call “conservative military revenge fantasy.” It’s a well-written, gripping read (like everything Schlichter writes). And the combination is successful, if the goal is to hold the reader’s interest and offer a frisson of conservative thrills.

But is it realistic? Does it accurately predict the possibility and depict the likely result of a negotiated split of the United States, and the subsequent trajectories of the two successor countries? (That’s two countries in three parts, since Schlichter has the West and part of the East Coast forming one country—not dissimilar to East and West Pakistan, which is not a promising precedent.)

My conclusion is that “People’s Republic” is fairly realistic, with caveats I outline below. If the book has an overriding flaw, it is that it posits a completely Manichean view of the United States, where virtue and vice is clear in each citizen. Reality is more complicated, and even to the extent virtue and vice are binary within a person, each state has many of each type of citizen. But Schlichter is surely correct that in the main, among our political, ruling class, divisions between virtue and vice ARE clear today. Projected forward, this ruling class virtue/vice split could easily lead to a world of the type Schlichter envisions.

Of course, “realistic” is all relative, since, as Yogi Berra supposedly said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” But implicit in “People’s Republic” are certain premises which it’s worth examining. That said, much of the book is really satire—not so much in its description of the economic policies of the successor countries, which is pretty much historically derived, but in its scathing description of the further development of the cultural Marxism of identity politics which is largely unfettered today, but if truly unfettered, would be (and at the rate we’re going, will be) an evil of the first order. Nonetheless, you have to ignore the satire to examine the realism, as amusing as the satire is at times.

On to examining realism. One very basic premise of the book, about which few would disagree, is that America is today very politically divided. Schlichter posits that these divisions lead to a negotiated split of Red and Blue states, during the Hillary Clinton administration, pursuant to the Treaty of St. Louis. The Red states call themselves the United States, with their capital in Dallas, and thrive. The Blue states call themselves the “People’s Republic,” and proceed for the next fifteen years to run themselves economically and socially into the ground in the manner of every leftist state ever, from the Soviet Union to Venezuela. Low-level violence results and the two countries are basically at violent odds, though not in open warfare.

Is it realistic to suppose our current divisions could lead to such a negotiated split of states? At first glance, it seems to anybody with knowledge of history that our current divisions are not historically abnormal—rather, the era of internal comity everyone looks to, from roughly 1950 through 1970, was the abnormal era. Leaving aside the obvious example of the run-up to the Civil War, the actual default mode among American political participants since colonial times has been vitriol without violence, so perhaps today is nothing new and there is no reason to believe it will lead to anything new.

Three things make today’s division unique, though. First, the enormous size, and even more importantly reach and power, of today’s government effectively require that everyone be involved in politics. Prior to the modern era, a citizen who simply wanted to live his life, not be involved in politics and not interact with the government would find that quite easy. Not today. Whether you are interested in the government or not, the government is interested in you. It is interested in aggressively taxing you, regulating you, surveilling you, and making sure you jump to it, or be ruined and branded a thought criminal, when members of Approved Grievance Groups demand you bake them a wedding cake. This dominance of the government of everyday personal life is totally unprecedented in American history, and it multiplies the impact of any political division.

Second, extreme ignorance and irrationality characterize the vast majority of political discourse today. In any prior American era, an uneducated person who offered neither reasoning nor evidence would not have dared to offer his opinion in the public square, for he would have been laughed at and humiliated by all other participants. “Delete your account,” or its nineteenth-century equivalent, was not considered a suitable riposte in the days when thousands came to see, follow, and discuss the hours-long Lincoln-Douglas debates. Nobody thought the opinions of ignorant and unintelligent entertainers were of any importance or consequence. Nobody would have thought, much less put forward, the idea that traits such as the right skin color or activity in the bedroom were substitutes for accomplishment, qualifications for societal acclaim and reward, while actual accomplishments by those with the wrong skin color or wrong social views were the mere happenstance of their supposed “privilege.” (That racism existed and even dominated in some areas is not to the contrary; racism does not pretend that the right skin color shows accomplishment, but claims inherent superiority.) If you did voice such ideas, you would have been punched in the face to general applause, or sent for psychiatric evaluation (by a doctor who recognized gender dysphoria not as a sign of virtue, but rather as a severe mental illness). Failure to follow basic logic was a one-way ticket to ignominy and obscurity in any national political actor—or it would have been, had any such mental defectives aspired to national office. Today, all these gross defects are the norm, further reducing any common ground.

Third, America’s political participants (those that can reason, that is) no longer share in any way a common vision of the human good and of human nature. In past generations, the idea that human nature was infinitely malleable, and that remaking humanity was desirable in the pursuit both of extreme individualism and of allowing the State to mold correct thought and action, would have been regarded by all as the pernicious fruit of unclean nihilist philosophers. Not today. And in past generations, that human good could be accomplished by everybody being wholly dominated by the State was regarded by all as antithetical to the bedrock of America. Not today. That so few core beliefs are held in common further exacerbates division.

So, it’s plausible that today’s divisions are extreme by historical standards—perhaps as extreme as, say, those of 1855, though for different reasons. Today we have less violence (so far), and more irrationality, but the degree of the divisions may be comparable, and may be insurmountable and irresolvable. And it’s plausible that to the extent this reality is recognized by those in power, probably as the result of key flashpoints (Schlichter mentions in “People’s Republic” Clinton’s attempt to seize guns in Red states, an entirely plausible scenario), a negotiated settlement might be attractive to those not interested in Civil War Two. Whether any of this is likely, I don’t know. But it’s realistic enough, unfortunately.

Somewhat less realistic is Schlichter’s vision of a relatively clean division among Red and Blue states. The common idea of monolithic blue and red states is pretty clearly incorrect. Within any state are many people, and at least some geographic concentrations, of both Red and Blue. And no geographic unit, even small ones, is homogenous. You can find Trump supporters in San Francisco, no doubt (although given the casual low-level violence that characterizes today’s “progressives,” doubtless they mostly keep their support to themselves.) You can find Clinton supporters all over Red states. And so forth. This reality would immeasurably complicate any split.

Schlichter nods to this mixture of Red and Blue by mentioning how, after the split, many people moved from one area to another. He also nods to it by positing separation not strictly along state borders. He views movement as mostly voluntary—essentially, parasites leaving the red states since their parasitism is no longer tolerated, and producers leaving the blue states, since those states are now totally free to engage in classic leftist/fascist appropriation of property and suppression of opinion.

While such movement might occur, it has never occurred in modern history without the incentive provided by violence. People simply don’t want to pick up and leave their homes and lives; they will only leave en masse if they are threatened with violence, and that begets actual violence, which begets more actual violence, usually ending in mass death. See, e.g., East Prussia in 1945; India in 1947; Yugoslavia in 1991; Syria now. It’s very, very optimistic to posit, as Schlichter does, a negotiated separation, followed by peaceful migration, only then followed by deteriorating relations. This is particularly true since parasites rarely see themselves as parasites and producers are not prone to abandon fixed means of production—in both cases, they are optimistic things will work out OK for them, though of course they rarely do. Yes, Schlichter does posit violence—for example, Southern Indiana as the site of extensive guerrilla warfare as the sides contend over whether it will be Red or Blue. But his posited orderly separation seems very unrealistic.

Finally, the most unrealistic part of the book is that Schlichter thinks that Red states are generally virtuous and Blue states not virtuous. That’s certainly true of the political class in clearly Red and Blue states. California, if left to govern itself, would quickly collapse under the weight of leftism, no different than Venezuela, and would immediately begin a totalitarian campaign of suppressing illegal thought, such as orthodox Christianity. (That California today continues to do as well as it does economically is not to the contrary—that’s purely a result of eating the seed corn stored up by generations of Red state policies that made California what it is today, and that the leftists who govern California are still somewhat constrained by the US Constitution.)

However, the actual people in clearly Red and Blue states are not as clearly virtuous or not virtuous. Sure, the virtue quotient is high in Amish country, or in the rural areas of the Upper Midwest, and the virtue quotient is low in large areas of the wealthy urban East Coast. But the same sharp divisions don’t hold across the board: urban areas of any Red state are not virtuous, in the main, and more importantly, most rural areas of most Red states are very much not virtuous. They’re not philosophically leftist, either, but you only have to read J.D. Vance’s recent “Hillbilly Elegy” to realize that the moral fiber and cultural beliefs of very many Red state Americans are not only not virtuous, but indistinguishable in practice from the parasitism that Schlichter ascribes only to Blue state residents. The world is not clearly divided into parasites and producers, and vice and virtue exist in many other contexts than those two groups.

So perhaps “People’s Republic” isn’t wholly realistic. But it’s not wholly unrealistic, either. And, it is important to remember, that massive political changes always seem impossible. Until they don’t.