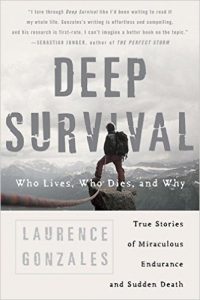

I read Laurence Gonzales’ “Deep Survival: Who Lives, Who Dies, And Why” as a counterpoint to Amanda Ripley’s “The Unthinkable.” Both are survivor books, very different in their approach, but with significant conclusions in common. Gonzales focuses more on accidents: unexpected twists that challenge people in stressful situations they chose to put themselves in, primarily wilderness and sporting recreational activities. Gonzales focuses little on true disasters, where our daily lives are suddenly interrupted by a wholly unexpected catastrophic and immediately life threatening event from which we must escape; Ripley focuses on true disasters. Gonzales focuses a lot on scientific, technical biological explanations; Ripley talks a lot about pseudo-scientific evolutionary biology. Gonzales is a more florid writer on a semi-autobiographical quest following a life of adventure; Ripley is a straightforward young writer trying to analyze what others do.

I read Laurence Gonzales’ “Deep Survival: Who Lives, Who Dies, And Why” as a counterpoint to Amanda Ripley’s “The Unthinkable.” Both are survivor books, very different in their approach, but with significant conclusions in common. Gonzales focuses more on accidents: unexpected twists that challenge people in stressful situations they chose to put themselves in, primarily wilderness and sporting recreational activities. Gonzales focuses little on true disasters, where our daily lives are suddenly interrupted by a wholly unexpected catastrophic and immediately life threatening event from which we must escape; Ripley focuses on true disasters. Gonzales focuses a lot on scientific, technical biological explanations; Ripley talks a lot about pseudo-scientific evolutionary biology. Gonzales is a more florid writer on a semi-autobiographical quest following a life of adventure; Ripley is a straightforward young writer trying to analyze what others do.

But this review is about Gonzales’ book, which aspires to “tell people [not] what to do but rather to be a search for a deeper understanding that will allow them to know what to do when the time comes.” His book tries to provide an overarching philosophy, really, for life survival, not just survival when you’re lost in the woods or hanging off a mountain. In fact, if there is a unifying theme of “Deep Survival,” other than survival itself, it is Stoicism. Quotations from Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius litter the book, and their ideas permeate every page. For example, from Epictetus: “On the occasion of every accident that befalls you, remember to turn to yourself and inquire what power you have for turning it to use.” This is because Gonzales believes, with demonstrated reason, that a Stoic approach to unexpected twists in life will maximize your chances for survival, in whatever situation you find yourself.

Gonzales ties all his stories and thoughts back to himself—back to his own growing appreciation for these principles he discovers during his life, and most of all back to his father’s experiences in World War Two and the rest of his life (he was a bomber pilot alive at the time this book was written, 2004). If you don’t like the personal angle, it may seem a bit navel-gazing. But he does a good job making himself and his family relevant, and after all, it’s his book, not merely a textbook for the wanna-be survivor.

Gonzales spends the first half of the book evaluating “How Accidents Happen.” In other words, most of what he focuses on is preventable survival problems. For him, if you stay home, there will be no survival problem. And, for the most part, if you go out into the wilderness and make the right choices, there will also be no survival problem. What Gonzales wants to know in this section is why people act in ways that create situations in which they must survive. His conclusion, shot through the book, is that it’s down to uncontrollable emotions, mostly for bad, but also for good. Quoting Remarque’s description in “All Quiet On The Western Front” of men who, having been at the front for a while, thrown themselves to the ground on sheer reflex, even before they can hear or sense a shell, Gonzales concludes “Emotion is an instinctive response aimed at self-preservation.” But that same instinctive response can also betray.

There is much talk of dopamine, brain structures, stress hormones, memory, and, in the end, “that quality which is perhaps the only one which may be said with certainty to make for success, self-control.” Our brains conspire to impel us by inciting emotions to do things that are not rational and not a good idea, but seem like a good idea to our brains. We need this type of decision making, since it is fast and effective, but it can kill us, if the emotion leads us to do something objectively stupid. Panic is only one of those emotions; pleasurable emotions are also extremely powerful. Controlling those emotions without losing their benefit is everything. And not just the control of manipulation—also the control of knowing what you don’t know. “A survivor expects the world to keep changing and keeps his senses always tuned to: What’s up? The survivor is continuously adapting.” “[T]he survivor ‘does not impose pre-existing patterns on new information, but rather allows new information to reshape [his mental models].’”

Of course, even choosing activities carefully while engaging in rigid self-control is often not enough. Accident always happen; it is the nature of systems, even simple systems. Small failures are self-correcting or at least not catastrophic, until the day they combine with other happenings to create total failure. As with a sand pile, which slides and collapses in unpredictable ways, you can tell that an accident will happen despite your best efforts, but not how or when. (It helps, of course, not to be stupid or have undesirable characteristics. Gonzales, like Ripley, casually slags fat people as unlikely to survive.) This is a commonality of systems: Gonzales notes that Clausewitz pointed out that military systems seemed simple, and therefore easy to manage, but “terrible friction . . . is everywhere in contact with chance, with consequences that are impossible to calculate.” Again, Clausewitz says a general must not “expect a level of precision in his operation that simply cannot be achieved owing to this very friction.” And trying to impose our own reality on actual reality when that friction starts to bite is disastrous.

Even if you choose carefully and have self-control, and avoid a system failure, you may still end up in a survival situation by simple failure of knowledge. If you don’t bother to inquire how the local waves differ from the waves you are familiar with, you may end up in trouble that you could have easily avoided. Gonzales does not promise that everything will be OK; he merely offers analysis and advice for maximizing the chance of avoiding problems.

Gonzales then turns to “Survival”—what to do when, for whatever reason, you’ve ended up in a survival situation. Many people “bend the map”—they try to, when lost in an unfamiliar area, rationalize how they are really in a familiar area. Don’t do that. Be as Stoic as possible. Accept your fate yet work to change it. Never follow rules given by others just because they are rules or because they are the group. Never give up. Fatigue is mostly psychological and difficult to recover from; rest proactively rather than pushing yourself. Balance risk and reward, then act decisively—be a “man of action.” Pray—even if it doesn’t work, it helps you focus and take action. (Although neither Gonzales nor Ripley emphasize it, both note that religious people are far more likely to survive.) “Plan the flight and fly the plan. But don’t fall in love with the plan.” Give yourself small goals and achieve small successes; follow a routine; create order. Focus on yourself, not on blaming others, or relying on them. And, ultimately, you may still die. “But what can be earned is a certain nobility—not in the sense of aristocratic status but in the sense of striving for quality and dignity of behavior and living.” The last is said by a wilderness firefighter of his daily job, but it can just as well be applied to a survivor in a single desperate situation.

None of what Gonzales says is all that startling. I imagine many of us would list some variations on these if asked the question, “what should one do to survive?” But Gonzales weaves these principles into a coherent whole, and links them to a range of interesting stories about real people. As with Ripley’s book, whose more cut-and-dried lessons Gonzales echoes, the reader can benefit quite a bit from this book, if you read carefully and absorb the lessons.