In the United States, most of us glimpse Venezuela in flashes. We know that Hugo Chavez is dead, and we know that his socialism has run Venezuela into the ground. As of this writing, in August 2015, it is a crime-ridden hellhole that has reached the stage of military confiscation of foodstuffs from farmers for redistribution, and is declining fast to Zimbabwe levels. But most of us don’t know more. That’s where this relatively short book provides real value.

In the United States, most of us glimpse Venezuela in flashes. We know that Hugo Chavez is dead, and we know that his socialism has run Venezuela into the ground. As of this writing, in August 2015, it is a crime-ridden hellhole that has reached the stage of military confiscation of foodstuffs from farmers for redistribution, and is declining fast to Zimbabwe levels. But most of us don’t know more. That’s where this relatively short book provides real value.

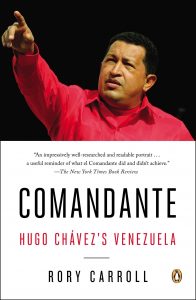

Carroll’s book, written shortly before Chavez’s death, takes us through Chavez’s life, largely through anecdotal flashbacks from the present day. The author lived in Venezuela as a reporter for a UK newspaper for all the relevant time period, and he seems to be very well acquainted with all the complexities involved. He thinks Chavez a pernicious failure who took the gifts given to Venezuela and destroyed the country, and he demonstrates that with verve. Hardly a shocking conclusion, but given that most of us have no real idea of what happened in Venezuela, it is a compelling, as well as very useful, story.

It’s compelling because of the people and their stories. Carroll draws them very well, from all walks of life. And Venezuela is a useful case study because it shows a possible future for the United States both in terms of our social comity and in the rule of law. American conservatives frequently prophesy doom from following our current course, conjuring apocalypses like Communism or the French Revolution. But Venezuela, a purgatory rather than an apocalypse, is a more likely future.

As to comity, we are more polarized in the US than we used to be, thanks mostly to the deliberately divisive Alinskyite tactics of Obama and his sycophants in the ruling class, but we have nothing on Venezuela. Carroll notes how popular Chavez was when first elected, in the manner of many strong men through the ages, elected to “fix the country.” (The original Roman dictators, of course, were appointed for exactly that purpose.) But then Chavez immediately took the country down a divisive path—“Millions underwent a transformation, detaching from the collective exhilaration of Chavez’s inauguration by growing puzzled, then anxious, then enraged. Millions of others, however, stayed loyal. Their ardor for Chavez burned with greater intensity.” Carroll also notes “the moment hatred infected both sides with a recklessness bordering on madness.” True, some of this has happened here, and there are echoes of Obama in 2008. But the viciousness in Venezuela is nothing like the US has in its modern political culture. Twitter mobs are not the same thing.

As to the rule of law, while it was largely destroyed in Venezuela, Chavez ran no gulags or torture chambers, and few political killings have occurred. Not many people were even jailed. On the other hand, opponents of Chavez faced and face real costs and dangers. The careers and livelihoods of anyone who opposed the regime were (and presumably still are) deliberately attacked and destroyed, using centralized lists of opponents, wiretapping, vicious abuse on television, and other devices short of violence. Chavez’s Venezuela shows what happens when erosion of the rule of law is combined with fantasy economic thinking.

We in the US are nowhere near the state that Venezuela is in—but we have arguably started down the road. We see the destruction of political opponents in politically motivated prosecutions for “crimes,” and in how already social conservatives are hounded from the public square and know, if they want to keep their job at Apple or Wal-Mart, to keep their mouths shut. We see the erosion of the rule of law in the Supreme Court’s Obergefell and King decisions this summer, and in the Internal Revenue Service, implicitly or explicitly directed by Obama, feloniously persecuting conservatives. We see Gibson Guitars, whose owner made the mistake of donating to Republicans, shut down by heavily armed federal agents for a fantasy violation of a foreign law, while his Democratic-contributing competitors are never touched. We see Obama continuously unilaterally and illegally decide to change the law, whether in rewriting Obamacare to say the opposite of what it says, or in admitting millions of illegal immigrants by fiat. We’re not Venezuela, though. Yet.

That we’re not Venezuela is not an accident, of course—it’s the result of 150 years of Madisonian government and Madisonian virtue, which even under continuous assault since the New Deal still bears fruit for our nation. But this repository of virtue can’t last forever.

There are some complaints about “Commandante” from Chavez cheerleaders, as there always are in such cases, where someone dares criticize an icon of the Left. Many or most of the “best people” thought the Western press gave Stalin too hard a time, and believed with all their heart that Alger Hiss was innocent. Wishful thinking is very powerful. But those complaints are silly—you can tell that book is objective about Chavez by noticing where Carroll is not objective, because he is clearly a man of the Left. Not only was his purpose in living in Venezuela to work for the left-wing Guardian newspaper, but he fairly spits venom any time any conservative is mentioned, inside or outside Venezuela, and he reserves negative adjectives solely for conservatives. Chavez’s opponents are “tomato-faced aristocrats.” The US shored up “any brute who could squelch socialists in Latin America.” Reagan’s entire Latin America policy was “facilitat[ing] right wing dictators’ war crimes.” And so on. Tiresome, but at least it should insulate Carroll from any charge that his criticisms of Chavez result from support for his opponents.

Aside from the political lessons, “Commandante” is also simply an enjoyable, well-written and interesting book, which I highly recommend.