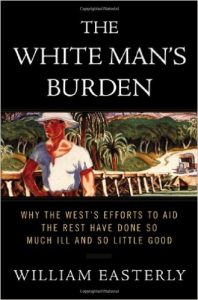

“The White Man’s Burden,” despite its inflammatory title, is a measured analysis of the ability of the West to help alleviate poverty in the rest of the world. The title is actually ironic, for the book concludes, in essence, that most of the burden the West has taken on has led to no improvement and much waste. This book is a companion, in many ways, to Easterly’s later book “The Tyranny of Experts.” It also has much in common with other books focusing on both the Great Divergence and the lifting of the poor out of poverty, in particular Angus Deaton’s recent book, “The Great Escape,” and James C. Scott’s seminal “Seeing Like A State.”

“The White Man’s Burden,” despite its inflammatory title, is a measured analysis of the ability of the West to help alleviate poverty in the rest of the world. The title is actually ironic, for the book concludes, in essence, that most of the burden the West has taken on has led to no improvement and much waste. This book is a companion, in many ways, to Easterly’s later book “The Tyranny of Experts.” It also has much in common with other books focusing on both the Great Divergence and the lifting of the poor out of poverty, in particular Angus Deaton’s recent book, “The Great Escape,” and James C. Scott’s seminal “Seeing Like A State.”

Easterly’s general framework is to contrast “Planners” and “Searchers.” Planners are what we typically think of when we think of development aid. They are external organizations like the United Nations or the Gates Foundation, well-funded, pursuing a range of big, difficult-to-achieve goals. Searchers are smaller, usually locally-based organizations and people, focusing on smaller, quickly achievable goals, where the methods used are adjusted based on immediate evaluation and feedback. The argument of the book is that Planners, totally dominant in the development industry for 60 years, have failed miserably, except at making people in the West feel good about themselves, and it is time for Searchers to dominate.

The mantra of the Planners is that of Bob Geldof: “Something must be done; anything must be done; whether it works or not.” Usually, it is hard to determine if the goals of Planners have really been accomplished, so accountability is minimal, and feedback adjustment loops do not exist. Nobody ever really investigates whether progress, and the right progress, has been made, and adjusts accordingly. Nobody is willing to admit that tradeoffs have to be made in the allocation of resources. Instead, in a few years, another call goes out for another giant, costly, shotgun-type development program.

An example of the difference between Planners and Searchers is anti-malarial mosquito nets. You’ve heard of these—they’re cheap, and extremely effective in reducing disease and mortality, particularly in children and pregnant women. Much money has been spent on distributing them for free as part of big Plans. What you probably haven’t heard is that when free nets are given out to people, they take them and use it for other purposes they value more highly, such as using them for fishing nets or wedding veils. (While Easterly doesn’t mention it, a side effect of this well-intended program is the destruction of African fish populations—see http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/25/world/africa/mosquito-nets-for-malaria-spawn-new-epidemic-overfishing.html?_r=0) Therefore, most of the mosquito nets don’t reach their intended targets. This is a natural consequence of providing a free good—it distorts the incentive mechanisms inherent in the free market, leading to all sorts of unintended consequences. But great success has been achieved by a small, Searcher, organization in Malawi modifying the Plan, by selling the nets, cheaply, directly to pregnant women and mothers, where the selling nurse also gets to keep a small profit to incentivize her. Because the end users paid for them, and thus have a stake in them, their actual use is nearly universal. In other countries, where Planners distribute them free, the vast majority of the nets are not used, or not used for their intended purpose.

But even though central planning has been shown, in every walk of life, to be a defective nightmare, Planners still dominate the development industry. What Easterly calls “The Big Push” is still the universal development model. The prototypical example is the UN’s Millennium Development Goals, which also involves private organizations, notably the Gates Foundation. Easterly goes to considerable length to demonstrate exactly how and why Big Pushes don’t help poor people become not poor. Among other things, he demonstrates that is a fiction that there is a “poverty trap” where countries need external help to jump-start their growth. In fact, most countries that can grow do grow, regardless of external aid, and those that can’t, don’t. (This is the essence of Angus Deaton’s argument as well.) Therefore, Big Pushes are a waste of money.

Rather, Easterly argues that what developing countries need is the rule of law (and democracy, at least to the extent it helps the government respond to actual needs), and free markets. Development aid is frequently anti-democracy, because it props up non-democratic regimes. In fact, development agencies dislike democracy in practice, because grand plans concocted by specialists (what James C. Scott, whom Easterly quotes to this effect, called “high modernism,” and not as a compliment) are easily frustrated in democracies.

Easterly also gives innumerable examples of the heinous bureaucratese that dominates and enervates the development industry. The norm seems to be mealy-mouthed, passive-voice, voluminous reports that say nothing much but insist that more money is needed to achieve the success that is finally just around the corner. His own background is the World Bank, so Easterly certainly has first-hand familiarity. I’m pretty sure, though, that he’s not welcome at World Bank parties anymore.

Of course, Easterly isn’t going to just throw his hands up and declare that aid is stupid. He is not opposed to aid—he wants it implemented in an incremental, accountable, properly incentivized fashion by Searchers, instead of spent poorly by unaccountable, utopian, not-very-bright Planners. While he is careful to note there is no panacea, and probably he would admit there is little reason for optimism, he also offers narrow specific methods for improving aid. He suggests more approaches, even radical approaches, be tried and the results examined, such as development vouchers, where the poor themselves choose how to allocate aid. He endorses the crowdfunding of GlobalGiving.com (he wrote this in 2006, and it still appears to be going strong in 2015). In sum, he wants the poor to be given tools to create their own future.

One highly original and useful idea is to target aid to project maintenance. Most Western aid goes to grandiose projects that make both donors and recipients look good—dams, road networks, school buildings. In reality, though, once the bunting comes down and the politicians leave, such projects decay because the politically dysfunctional aid recipients fail to maintain the dynamos, fix the roads, or provide textbooks. And donors don’t want to fund ongoing maintenance, repair and consumables, because they believe that local people should take some responsibility. But they don’t. Easterly says Western aid organizations should just “bite the bullet and permanently fund” ongoing costs for projects, accepting that recipients are not going to reliably do it themselves.

Easterly does go somewhat off the rails toward the end of the book, in which he criticizes past colonialism and modern (American) “imperialism” for creating problems and approaching development in the same way as modern Planners. I’m not really sure what the point of these two sections is, other than perhaps to prevent the author being perceived as conservative due to his bias towards free markets as necessary for development. No doubt the hasty British departure from, and partition of, India in 1948 created all sort of bad things. But does anyone really think that India would be better off if the British had never ruled, or that the British were the ones who wanted partition? And Nehru-style socialism, rather than colonial after-effects, was responsible for decades of Indian stagnation, only reversed when India shook off that socialism in the 1990s. Doubtless Western national security interests can prop up bad regimes and create ill effects, such as in Pakistan and Sudan, but does anybody really think that either Pakistan or Sudan is ever going to be anything but a crappy country? I don’t.

Easterly also seems to think that American attempts to engage in nation-building, usually combined with serving American security interests, are a disaster from a development perspective. He may be right, but his history is pretty selective, and often distorted. For some reason he spends a lot of time on the Nicaraguan civil war of the 1980s, not an exercise in nation-building, where he continuously slanders the heroic indigenous resistance (the Contras) and swallows the left-wing propaganda of the time disseminated by the Communist Sandinistas and their Western lackeys. He bizarrely refers to the Communist-friendly and violently anti-American pressure group Americas Watch simply as a “human rights organization,” and he blithely states that “the Contras executed on the spot any civilian associated with the Sandinistas.” The Contras are all “homicidal” and so forth; no negative adjective or stigma attaches to the terroristic Sandinistas and their mass graves.

Actually, killing of prominent local civilians as a terror tactic has always been a key and required ideological element of left-wing and Communist revolutionaries, from Lenin on, including the FMLN in El Salvador (notorious for killing scores of village mayors) and Sendero Luminoso in Peru. Such killing has generally not been associated with right-wing organizations (admittedly a much smaller set of data, given that right-wing organizations, revolutionary or government, have been responsible globally for a miniscule fraction of the tens of millions killed by left-wing groups). While there may have been occasional such incidents involving the Contras, they were very few, or they would have been extensively publicized at the time, which they weren’t.

I remember once a group of Contras in the field, in 1985, killed a military prisoner they had, because they were being pursued and could not transport the prisoner silently. A Western photographer happened to be with them. The resulting picture was headline news for days, if not weeks, in the United States, as the media desperately tried to use the “news” to attack the Contras, and by extension, President Reagan. The American media would have had a field day if they ever could have shown the Contras deliberately killed a single civilian.

The Contras were an indigenous and generally popular resistance movement, which ultimately was able to overcome the Sandinistas in a free election (although credit has to be given to the Sandinistas for even having a free election, the only Communist state ever to voluntarily do so). That Easterly shows violent irrational bias against them is strange in someone who generally seems very even-keeled.

Easterly’s other blind spot is the same one found in “The Tyranny Of Experts”—Easterly never seems to consider that some cultures simply aren’t capable of advancement, no matter how much money or other aid is handed to them. He implicitly assumes that every culture wants the same thing and is capable of progress. He believes that Searchers can come to predominate in any culture, as they did in Japan, Botswana and Singapore, once backward and now very or more advanced. But that’s not always true, or maybe even often true. Afghanistan was a pit with a defective culture when Alexander the Great swept through; it was a pit when Winston Churchill fought the Pashtun in the 1890s on the Northwest Frontier; and it is a pit with a defective culture today. All the money in the world, no matter how distributed or applied, will not change that and there is nothing more futile than trying to force change on those who do not want to change. But Easterly is an optimist, so perhaps he does not see this, or perhaps he simply thinks pessimism will not help his cause. And the world can always use more realistic optimists.