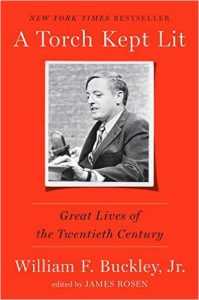

Of late, I have noticed much creeping, or rather galloping, nostalgia among National Review-type conservatives. Such nostalgia is doubtless a reaction to the current Trumpian trials of High Conservatism, whose leading lights must feel much like the characters in Toy Story 3, holding hands as they are fed into a fiery furnace. (The Toy Story characters survive, which probably distinguishes them from today’s leaders of High Conservatism.) “A Torch Kept Lit” offers a triple dose of nostalgia: William F. Buckley; eulogies of dead conservatives (and others); and a deep view of a dead time. And, like a papyrus scroll listing grain shipments on the Nile, it is redolent of ancient history, when High Conservatism mattered.

Of late, I have noticed much creeping, or rather galloping, nostalgia among National Review-type conservatives. Such nostalgia is doubtless a reaction to the current Trumpian trials of High Conservatism, whose leading lights must feel much like the characters in Toy Story 3, holding hands as they are fed into a fiery furnace. (The Toy Story characters survive, which probably distinguishes them from today’s leaders of High Conservatism.) “A Torch Kept Lit” offers a triple dose of nostalgia: William F. Buckley; eulogies of dead conservatives (and others); and a deep view of a dead time. And, like a papyrus scroll listing grain shipments on the Nile, it is redolent of ancient history, when High Conservatism mattered.

The blurb for “A Torch Kept Lit” promises that “William F. Buckley, Jr. is back—just when we need him most.” This fantasy, in a nutshell, is what’s wrong with today’s High Conservatism. Buckley is not back. He will never be back. He has joined the Church Triumphant. But if he were back, he would answer no need we have today. He was a man for his time, and not for our time. His brand of urbane, sophisticated conservatism, predicated on mutual respect among adversaries, on the existence of the rule of law, on shared values, on a belief that denying reality was disqualifying, and on the desirability of reasoned discourse, has no place where none of these things are true. What we DO need now is less clear, for no clear path forward or back exists, and so, to the dismay of Dr. Seuss, we inhabit the Waiting Place, “a most useless place.”

Why Buckley would have no impact today can be encapsulated in one non-political experience. I read much of this book while waiting in line in a federal government office (a customs office, for an interview for the Global Entry traveler program). Let’s leave aside the arrogant, peremptory manner of the federal employees, who (while working with modest efficiency) made very clear who were the Rulers and who were the Ruled. The waiting room was full and the wait was long. CNN Headline News was playing. We, and all of America, were eagerly informed about (a) a child who drove a car, avoiding an accident; (b) a man who took selfies after being attacked by a bear; (c) a fiery truck crash where the cargo, cookies, were baked; and many other such “news” stories, liberally larded with offensively unintelligent advertisements. That such tripe is demanded by consumers of news tells us why Buckley would, like Dostoevsky’s Christ, not be welcomed back today.

Buckley himself early pointed out the trend in this direction. In his thoughts on the death of Eleanor Roosevelt, in 1962, Buckley quoted James Burnham, summarizing Mrs. Roosevelt’s long postwar career. “Over whatever subject, plan, or issue Mrs. Roosevelt touches, she spreads a squidlike ink of directionless feeling. All distinctions are blurred, all analysis fouled, and in the murk clear thought is forever impossible.” Buckley concludes that her epitaph should read, “With all my heart and soul, I fought the syllogism.” That’s about right. Nobody today values the syllogism. Pretty much nobody even knows what a syllogism is. And that’s the problem, for Buckley’s entire life was built around the syllogism, as this book shows.

I don’t mean my negativity to reflect on this excellent book. After all, there is nothing wrong with nostalgia, if we do not allow ourselves to be lost in it. And, not infrequently, we can find in the past facts or reasoning that can help us today. Even if we find nothing directly useful, we can be amused, such as by Buckley’s comment (not in a eulogy, but noted by the book’s editor, James Rosen) about Lyndon Johnson, “It is widely known that whenever Senator Johnson feels the urge to act the statesman at the cost of a little political capital, he lies down until he gets over it.” Buckley’s eulogies are full of such pithy phrases, as well as more sonorous ones.

Echoes, or forebodings, of today’s travails can also be found in Buckley’s eulogies. For example, in his eulogy of Ronald Reagan, Buckley notes “how reassuring it was for us [to listen to] the Leader of the Free World who, to qualify convincingly as such, had after all to feel a total commitment to the Free World.” One can only wonder what Buckley would make of Barack Obama—a man who has only contempt for America, and thinks its only value is to atone for its unique sins by abasing itself. No wonder Obama reassures not at all, and fails to qualify convincingly both as the leader of America and of the Free World—he has no commitment to either.

None of these eulogies are hagiographies. Most political figures in this book, even allies, come in for some criticism, or at least an acknowledgement of their failings. For example, in 1965, Buckley knocked Winston Churchill: “It was Churchill who pledged a restored Europe, indeed a restored world order after the great war. He did not deliver us such a world.” Buckley blamed Churchill, in part, for “a world in which more people are slaves [today] than were slaves in the darkest hours of the Battle of Britain,” resulting, in part, from Churchill’s behavior at the end of the war toward Stalin. And Buckley ends his eulogy, “May he sleep more peacefully than some of those who depended on him.” Tough stuff.

The most poignant eulogies are of Buckley’s friends, such as the liberal Allard Lowenstein, killed by a deranged acquaintance in 1980. “His days, foreshortened, lived out the secular dissonances. ‘Behold, thou hast made my days as it were a span long, and mine age is even as nothing in respect of thee; and verily every man living is altogether vanity.’ . . . Let Nature then fill this vacuum. That is the challenge which, bereft, the friends of Allard Lowenstein hurl up to Nature, and to Nature’s God, prayerfully, demandingly, because today, Lord, our loneliness is great.”

Our loneliness is also great, though for different reasons. High Conservatism, like Buckley, is dead, though presumably Buckley realizes it, and National Review does not, yet. But despair, as Buckley was fond of noting, is a sin, and a great one. We cannot see what is next. Like Theoden King, we say to, and ask, ourselves: “The days have gone down in the West behind the hills into shadow. How did it come to this?” And like Theoden, not knowing what the future holds, our task must be therefore merely to gird ourselves for an uncertain and unknown battle, such that we may be both ready for any challenge, and able to strike in any direction.