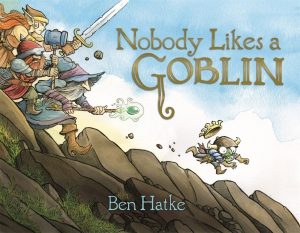

This is an outstanding children’s book. We got it for our children for Christmas and it became an instant favorite. It’s a clever instantiation of classic themes. On the surface, it’s a reversal of a typical Dungeons & Dragons story, casting the dungeon dwellers as the misunderstood heroes who triumph in the end, through pluck and determination. But I want to analyze it (though I am entirely sure that the author, Ben Hatke, does not intend this meaning at all) as a metaphor for the plight of social conservatives in today’s world, and the solutions for that plight. You may ask, what do goblins and dungeons have to do with social conservatives? You are about to find out!

This is an outstanding children’s book. We got it for our children for Christmas and it became an instant favorite. It’s a clever instantiation of classic themes. On the surface, it’s a reversal of a typical Dungeons & Dragons story, casting the dungeon dwellers as the misunderstood heroes who triumph in the end, through pluck and determination. But I want to analyze it (though I am entirely sure that the author, Ben Hatke, does not intend this meaning at all) as a metaphor for the plight of social conservatives in today’s world, and the solutions for that plight. You may ask, what do goblins and dungeons have to do with social conservatives? You are about to find out!

The story begins with the hero, the eponymous Goblin, living peacefully in a dungeon. He tends to the permanent things of his world—he lights the torches, he feeds the rats, he visits and converses with his best friend, Skeleton. He does not seek social change, much less some imagined abstract social justice; he does not make grand plans for remaking the world at the expense of its current inhabitants, for the alleged benefit of its future inhabitants; he does not attempt to rule over others for their putative benefit. He is content.

But this peaceful world is abruptly invaded and disturbed by a band of adventurers, who uproot the social order of the dungeon as out-of-date and therefore no longer allowable. They proceed to despoil the dungeon, destroying the society with no care for its function, how it got to be like it is, whether it serves the needs of its inhabitants, or any other organic concern. Doubtless they perceive the dungeon dwellers as bigots living in the past, on the wrong side of history.

Really, the adventurers are just social justice warriors in armor. They are even politically correct—their biggest warrior is a muscular “woman,” perhaps a “transgender” man (i.e., a mentally ill man delusionally believing he is a woman). If she is a real woman (the story does not make it clear), the adventurers include her in their group not for her abilities, since the reality is that no woman has ever fought successfully with plate armor and sword, but to smash gender “stereotypes” that result from admitting reality is real.

And, like social justice warriors and liberals in general, the adventurers steal from the producers in society and line their own pockets, no doubt telling everyone that they are improving the world, while they actually produce nothing of value themselves. Moreover, they confiscate all the weapons, presumably congratulating themselves on controlling weapons and keeping them out of the hands of the deplorables. And, finally, they cart off Skeleton. This is their gravest mistake—to greatly disturb the social conservative, Goblin, by attacking the core of his social existence. From this final injury arises Nemesis to bring low the hubris of the social justice warriors.

Goblin, like most social conservatives in America circa, say, to pick a random date, October 2016, is left feeling alienated after his life, his livelihood, and all he holds dear have been attacked and destroyed by rootless social justice warriors. Just like the owners of Memories Pizza, his life has been viciously assaulted by the bigoted, mighty and powerful. So he ventures out of the empty dungeon, to find the only other creature he knows, a local hill troll (from whom the social justice adventurers have confiscated his goose, presumably as a form of taxation). Troll advises Goblin not to seek his friend Skeleton in the wider world, for, after all, “nobody likes a goblin.”

Goblin, however, ignores this (“I’ll be okay”) and bravely forges out, over the mountains, and into the realms beyond. His position is like that of any social conservative, who has learned over the years it is best to keep his mouth shut and not venture forth, for he will be punished if his views become known by those who rule our culture. Nobody likes a social conservative, either, or at least none of those who have (or had) the power in our culture. But Goblin will prove that does not matter, for he realizes that to acknowledge reality as real itself gives strength.

Goblin crosses the mountains. The first person he finds is a farmer, who, it appears, has been taught by the liberal media to revile socially conservative goblins. Goblin asks if the farmer knows where Skeleton is. “Ack, a filthy goblin!”, the farmer shrieks, and chases Goblin. Goblin runs through a tavern filled with elves who are lazing around drinking during the day, presumably enjoying the fruits of getting jobs as diversity hires and therefore being entirely insulated from being fired for lack of job performance. They, seeing the social conservative as a threat to their unearned comfort and ease, join the chase (along with the human innkeeper, who sees that whatever he thinks about goblins, his economic interests lie in joining the mob, for otherwise he also will be persecuted and ruined).

By chance, in his flight, Goblin runs into the adventuring social justice warriors, who are carting off all the treasure, along with Skeleton and a random tied-up human woman. This latter is a metaphor for the way liberals claim to liberate women, but in reality often pursue policies antithetical to women, and moreover are happy to overlook actual ill treatment of women, such as Bill Clinton’s serial rape, to obtain their own, more important, personal benefits. Goblin grabs Skeleton and flees into the Haunted Swamp, hiding in a cave.

Skeleton, unable to fight (not having any muscles, though he was once a mighty warrior and king, something naturally not respected by the social justice warriors, since it is retrograde and patriarchal), comforts his friend as the liberal mob closes in. Loyalty, one of the key conservative virtues, is shown by both characters. Goblin despairs, saying “Troll was right. Nobody likes a goblin.” But Skeleton replies, “’Well, I like a Goblin.’ And the two friends sat together and waited for their doom.” They think they are alone; they have been told they are alone, and that they represent a doomed world, fit only to die and be cast onto the ash heap of progressive history.

But in a flash the world fractures and recrystallizes, new in form and substance. From the back of the cave, many eyes appear, and a voice asks “Do you know who else likes a goblin?” The answer: “MORE GOBLINS!” The cave is filled with previously voiceless goblins, suppressed by the elite and forced to hide themselves, even though, collectively, they have the real power. And they follow Goblin not just because he’s a goblin, since they reject identity politics as such, but mostly because he happens to be wearing Skeleton’s crown. They thereby acknowledge the critical role that excellence should play in the selection of leaders and the distribution of rewards, along with the importance of mixed government and hierarchy, rather than pure democracy with its anarchistic and atomistic ways.

All the goblins, together with the now-freed woman, the Troll’s goose, and a ghost from the Swamp, attack their enemies as they close in for the final kill. All the goblins are, of course, heavily armed, doubtless because they did not believe it when the elves and humans told them that sword registration was not a precursor to confiscation. As a result, they rout their enemies. The elves and the innkeeper flee. The freed woman, who fights as necessity dictates (for it is not that women cannot fight—it is that it is best for all if they not generally do so, but with the right weapons and motivation, they are more effective than men) routs the gender-bending adventurer, who, being only there for her social justice role, can’t actually fight. There is no flinching from the necessary—all the adventurer social justice warriors are killed, by implication, thus recognizing that some persecutions can only be ended by the permanent incapacitation of the persecutors. At no point do the goblins attempt persuasion or come to an phantasm middle ground; showing the traditional conservative virtues of determination, honor and courage, when they find it necessary, they attack, and they overcome.

At this point, the conservative victors have a choice to make. (Notably, like all conservative groupings, the collection of victors shows the true diversity produced by talent and circumstance, not the false diversity that exalts those lacking talent merely because they have a preferred skin color or other irrelevant characteristic.). They could extend their victory into the larger world, enforcing an ideology on others or simply ruling over them to prevent the recurrence of left-liberalism with its logical end of persecution of others, but they prefer to lead their lives in simplicity, harmony and order, having cleared the ground of its uncleanness. So they return beyond the Haunted Swamp, over the hills, and back to the dungeon (returning Troll’s property to him), and once again enjoy the simple pleasures of family and friends in the dungeon.

Perhaps this form of Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option is a mistake; perhaps their enemies will regroup and strike again. But maybe Goblin and his friends have chosen the better path, and, keeping their swords sharp, will do their best to carve out a world for their children and their children’s children, free of, and separate from, the evils of left-liberalism.