When I am dictator, which hopefully will be any day now, I am going to bring back what was once a crucial distinction. Namely, the sharp separation between the deserving and the undeserving poor. Theodore Dalrymple’s book shows both why that distinction is necessary, indeed absolutely essential, and why it has fallen from favor among those who decide society’s rules. Moreover, Life at the Bottom offers a wide range of food for related thoughts, so many that I am afraid, beginning this review, that it is likely to go on for a very long time. But at the end, I will solve all the problems for you. Strap in.

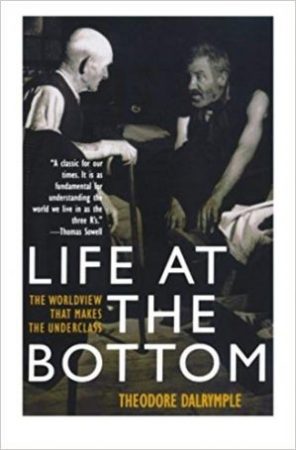

This book is a compilation of short articles written by Dalrymple for the London City Journal between 1994 and 2001. All of them take as their theme the condition of the British underclass, something to which the author was (he recently retired) exposed directly to for decades, working as a physician in a slum hospital and in a nearby prison. From his tens of thousands of patients, the life of each of whom he explored (he was a psychiatrist, not that the vast majority of his patients had any mental illness), he extracted a clear view of their lives, and the lives of all those around them. As a result, this book is not so much a compilation of anecdotes, but the grasping of a pattern, offering heft equal to books that rely more on statistical social science, such as Charles Murray’s Coming Apart, and more heft than books relying on news stories and abstract moralizing.

In fact, Dalrymple offers almost no moralizing at all. An atheist, he sometimes shifts uneasily in his seat when talking about morality, since he has nothing except utilitarian impact and unmoored societal consensus on which to base claims of morality. On balance, though, that perhaps makes his book more accessible, in these post-Christian days, though it is surely true that only with a recovery of morality, and enforced moral judgment, will any of the problems he bemoans actually be addressed. His lack of a moral frame is, perhaps, also why Dalrymple too often offers preemptive apologies, such as approving the laughable idea that today’s forced nonjudgmentalism is largely a reaction to “the cruel or unthinking application of moral codes in the past,” or sagely chanting the required overt falsehood that recent European immigration from inferior cultures is generally a good thing. The reader is best off just ignoring such apologies, which, as always, merely weaken strong arguments and serve no purpose other than corrupting the truth and surrendering to one’s enemies.

While the book’s stories blur into an endless round of squalor, violence, and every type of vice, several major themes run through the whole book, which collectively characterize the “worldview” of the underclass. The chief one is that all of British society, and the underclass most of all, has wholly absorbed to its detriment the philosophy of nonjudgmentalism. Everyone, except benighted reactionary outcasts, recoils from the idea of that one thing or action is or can be better, more worthwhile, or more moral than another. From that flow, directly or indirectly, most of the underclass’s problems—while the classes above them have retained, to some degree, the structures that permit them to avoid the price of nonjudgmentalism (this is, of course, Charles Murray’s point about America). Another is that the underclass has been taught to ignore reality—when Dalrymple points out to a young girl that, being weaker than them, she can always be physically battered by her boyfriends, and she should avoid situations that lead to her being beaten, she denies that she is physically weaker, chanting “That’s sexist!”, and goes back to get beaten some more. And along the same lines, healthy and reality-based views of masculinity and femininity have disappeared entirely.

A third is that the underclass denies any and all personal responsibility. When a man stabs someone, he says “The knife went in.” Jordan Peterson would be appalled (actually, he is appalled—I noticed after reading this book that it is on his list of recommended reading). A fourth is that they give no thought for the future, living in the eternal present; concomitantly, they have no aspirations to do or be something better. A fifth is that the underclass expects government handouts, that is, theft from the productive members of the society for their benefit, as an absolute, irrevocable, and non-discussable birthright. A sixth is their total ignorance—of all the thousands of Dalrymple’s patients, he says, only a few had more than the vaguest idea of when the Second World War took place. This is because teachers have abdicated their responsibility, plus any student who shows drive is torn down by his peers. A seventh is the fear that all the underclass lives in, a fear of crime committed by the most criminal among them, about which the police will do little or nothing. An eighth is that they have wholly absorbed the religion of emancipation, that they have no personal limits, but they instead have unfettered freedom to do exactly as they please, to be funded by others if that freedom needs money. A corollary to this is that no hierarchy of persons or values can be permitted, since everybody is aggressively and always equal (which reinforces lack of aspiration).

I use the term “underclass,” rather than “the poor,” deliberately, and for two reasons. One is that some people with limited income and assets are not part of the underclass, though they usually suffer as a result of their physical proximity to the underclass. The second is that no member of the underclass is actually poor at all. They may be “below the poverty line,” but since that line is set as a percentage of all incomes, we will always have the poor with us in that sense (which is not the sense in which Jesus used it). By any rational standard, every member of the underclass is wealthy, having, even without any source of earned income, free food, healthcare, cash, housing, transportation, and appliances. True, the incentives created by the programs that provide these handouts to the underclass are often perverse, such as encouraging the underclass to stay jobless (not that most of them need any encouragement) or encouraging them to stay unmarried and to have multiple children out of wedlock. But that does not change that, viewed objectively and historically, the British underclass is actually prosperous.

And where does the underclass get these habits of thought? Why, from their rulers, naturally, who have been feeding leftist claptrap to them through news and entertainment, and through the minions of government, for decades. Most of these habits are the liquid in the poisoned chalice of the modern Left, the nasty fruit of the Frankfurt School. Whether it is their teachers, the hundreds of thousands of social workers who live equally parasitically off government handouts, television, newspapers, or slippery politicians like Tony Blair, none of these habits of thought are called out as bad and requiring immediate correction by harsh means. The other classes don’t pay the penalty for these ideologically driven ideas, but they do get to feel smugly superior and righteous, though they keep well away from where the underclass lives. To be sure, there’s just as much, if not more, rot throughout the rest of British society, also requiring immediate correction through harsh measures. It’s just a different type of rot. But when an entire society requires a hugely unpleasant reset, it’s no surprise that Lotos-eating gets the nod as a preferred alternative.

Americans like me can’t really believe it’s this bad in England. Certainly, what the author describes is similar to some areas of America (just read J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, though the underclass there is not quite as degraded as the one Dalrymple portrays). The reader wonders if the author is exaggerating. Not to mention that, if it was this bad in England twenty years ago, how long could this go on? What’s it like today? Dalrymple, though now retired, is still prolifically writing for the City Journal. Few recent writings of his touch directly on the British underclass, though those that do, don’t suggest things have changed for the better. Have things gotten worse? Have things settled down to a permanent state of having X% of English citizens live in crime-ridden blob-like squalor? Is it just that polite society ignores and stays out of the areas where the poor live, such that areas of Britain are like certain suburbs of Paris, out of sight and out of mind except when the rioting begins? It’s essentially impossible to get straight answers to questions like this, unfortunately, at least as an American.

Because this book focuses purely on Britain, and never mentions the United States, it offers other interesting comparisons to matters here. Most of all it shows that, whatever our local racists may say, who is in the underclass has nothing at all to do with race. The majority of the British underclass is white, and its pathologies are a purely cultural phenomenon, since none of these people, or their ancestors, suffered any type of persecution they could claim explains their lot—in fact, they were offered all the benefits of the greatest civilization the world has ever seen, the pre-late modern West. Further proving that culture is all, Dalyrmple points out that some Indian subcontinent groups (notably Sikhs) largely avoid falling into the underclass; others plummet rapidly into it. Immigrants from Jamaica dwell (metaphorically) largely in the cellar; those from Barbados do not. The author narrates with grim amusement how doctors come from Mumbai and Manila, brimming with great sympathy for the poor and hugely impressed with how well the British government provides for the poor, and are quickly disillusioned by the underclass’s total ingratitude and failure to take advantage of what they are offered, ultimately concluding that those living in the slums of the Third World are better off, overall, than the English underclass.

Another point of comparison is crime. It is very hard for a casual observer to get coherent data on crime in the United Kingdom. Not only does the government not present it longitudinally in any form easily available to the public, there are different sets (is Scotland included, for example?), and widespread consensus that a great many crimes are simply not reported because the police don’t care and can’t be bothered (a theme that recurs repeatedly in this book). However, the left-wing Guardian newspaper noted in 2017 that “Police-recorded crime has risen by 10% across England and Wales—the largest annual rise for a decade—according to the Office for National Statistics. The latest crime figures for [March 2016 to March 2017] also show an 18% rise in violent crime, including a 20% surge in gun and knife crime. The official figures also show a 26% rise in the homicide rate. More alarmingly, the statisticians say the rise in crime is accelerating, with a 3% increase recorded in the year to March 2015, followed by an 8% rise in the following year, and now a 10% increase in the 12 months to this March. . . . [T]he country is becoming increasingly violent in nature, with gun crime rising 23% to 6,375 offences, largely driven by an increase in the use of handguns.” From other data, it’s quite clear that all violent and property crimes are much higher in England than America, except for homicide (which is especially relatively under-reported in England for multiple reasons), and that the UK has not experienced the massive drop in crime that America has in the past three decades, at least not to nearly the same degree.

But these statistics don’t capture a related qualitative difference between crime in England and America. It’s hard for people like me to grasp the oppression of the British underclass by crime, something Dalrymple emphasizes. They can do nothing to defend themselves or to preserve their dignity; they must just sit there and take it. If they defend themselves in any way, they go to jail, as numerous recent cases have shown. When, having disarmed the law-abiding populace, the British elite now shriek that knives are evil and that kitchen knives should only be sold with blunted points, it’s hard to imagine the oppressive feeling of powerlessness and fear that must confine the British underclass. In most of free America, where I live, if I am afraid I may be exposed to crime, to prevent it, I simply carry a Glock. I carry it concealed for discretion, or on my side, visible to all, if I think that trouble may be walking the street, and, as a result, there is no trouble. Many others do as well, and as a result street crime and home invasions in free America are practically nonexistent. Aside from its practical benefit, that I and my family are safer, I can tell you from personal experience that the ability to be armed empowers us and adds dignity to our lives, real dignity, not the fake kind of dignity that Anthony Kennedy parades through Supreme Court opinions. That’s something the English underclass is denied.

There are other cultural lessons in this book for those of us outside the underclass, which is probably one hundred percent of the people reading this. Dalrymple often notes the unpleasant habit today of lower-class culture percolating upwards to infect other classes, a reversal of every society prior to the Western late modern. Tattoos are one example of this, but more generally, when rappers and seedy entertainers are taken as fashion and role models by the middle and upper classes, the culture is degraded, not enriched. All the habits of the underclass reinforce this rot, such as the canard that everyone is equal and thus we must believe that doggerel is poetry. But it’s not just body modification and ugly music that’s caught on among the upper classes—it’s loutish, drunken behavior in public, the casual use of obscene language, wife beating, and generally what used to be correctly called “lower class behavior.” (Contrary to feminist myth, wife beating, or to call it by its sanitized term, “domestic violence,” was not at all common outside the lower classes, until quite recently, because of social disapproval. Although, it is true that there are now precious few wives among the lower classes, so maybe the old term is now inaccurate.) Needless to say, voluntary degradation is not the way to build a society that is going anyplace good, though almost nobody dares to say so.

Another cultural lesson, with historical aspects, applicable to the United States, is that the destruction of communities by forcing the poor into planned, Le Corbusier-type Brutalist concrete hellholes was driven exclusively by left-wing ideology. Nobody disputes this in Britain, which is why Dalyrmple just states the fact as obvious and undisputed. The same ideology drove similar destruction and construction in America, which is no surprise. But in recent decades, because of the total failure of such housing in America and the harm it caused the underclass, the Left has taken to lying and saying that it was racist conservatives who pushed building Cabrini-Green, the Robert Taylor homes, and other fantastically pernicious housing projects. No doubt racists (many, or mostly, left-wing) have negatively affected housing patterns for African Americans, but high-rise public housing is not an example of that; in both Britain and America, it was and is solely the responsibility of the reality-unmoored, utopian Left. This book performs the service of exposing the lies of the American Left on this topic, since there was indisputably no racial element in this forced migration in the United Kingdom.

I also found it interesting that the term “Asians” as a general term for those from the Indian subcontinent does not appear once in this book. That suggests the usage is of quite recent vintage. My 1989 copy of the Second Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary does not list that use of the term; nor do the printed Additions through 1997. Like all politically chosen terms, it is also subject to ongoing forced change. In recent years, Sikhs and Hindus, annoyed that Muslim crimes such as terror and rape are characterized as being committed by “Asians,” have petitioned that the term not be used, although it is not clear what they want to substitute. (It’s not like the press is going to start calling Muslim crimes, “Muslim crimes.”) I’m not sure why the new term “Asians” was forced into common use, or what came before. I am told, by the shocked look on my English cousin’s face when I use it, that “Paki” is regarded now as a slur, so presumably “Asian” was brought in as a euphemism, which, like most euphemisms, clouded communication. So maybe the Sikhs now prefer to be called “Pakis” again, a slightly more accurate term, certainly, than “Asian,” and one which does not get them lumped in with child rapists.

Muslims don’t show up much in this book causing the problems they cause in Britain in the twenty-first century. Dalrymple wrote before a toxic brew of Muslim aggression and triumphalism, government fecklessness, and Left ideology, really started to poison Britain. Rumors and echoes of this show up occasionally, though, especially when the author notes that the police deliberately ignore crimes so as to avoid any possible claim of racism, demanding “Zero Intolerance.” (I wonder what Dalrymple thinks of the Yorkshire police’s current campaign to encourage reporting to the police of any non-criminal behavior that constitutes “hate,” while they ignore their actual job of fighting crime.) Part of the poison is terrorism, supported by a significant percentage of British Muslims. In 2017, a large survey showed that 25% of British Muslims were willing to openly support wholly replacing all British law with sharia law, and 33% supported killing anyone who insulted Muhammad. But far worse is the cultural poison of the Muslim underclass not related to terrorism, with the tip of the iceberg revealed by the Rotherham crimes (in Yorkshire), where Muslim men groomed more than a thousand non-Muslim girls for mass rape over many years, ignored by the police who were terrified of being called “racist.” (Such treatment of infidel women is both permitted and celebrated by mainstream, though not by any means exclusive, interpretations of Muslim law.) I suspect that even now Dalrymple doesn’t touch too much on these matters, since it is forbidden in Britain and you will be arrested if you say these things (I would be if I said the preceding paragraph on the street near a policeman). A recent column of Dalrymple’s noted that he keeps his mouth shut on certain topics, not because of fear of arrest (though maybe that too), but because if he talked about them “everyone I know would cut me dead.” The Muslim underclass is, though, at root just a specialized underclass problem, and ultimately all of these problems need a common solution; they cannot be addressed piecemeal.

If there is one overarching political lesson to be learned from this book, it is that democracy should be sharply limited. As long as the underclass has political power, it will be used to reinforce their pathologies (even though the source is not of the underclass). Only a fool or an ideologue would think that it is a good idea that any of the people who appear in this book be allowed to vote, or to have any say whatsoever in the governance of society. (Their interests could be protected by their betters, in the form of an institution such as the Roman plebeian tribunate, an underappreciated alternative to democracy.) The only plausible argument for allowing such a thing is that once you start limiting who can vote, where do you end? Well, I’ll be happy to supply an answer to that question—in brief, anyone who does not both stand on his own two feet and who does not have a defined, strong stake in society should not be allowed to vote. So anyone who receives individualized handouts from the government of any type, beyond purely incidental ones, including all government employees and contractors (with the exception of combat-likely military and combat veterans) should be immediately disenfranchised. And anyone without fixed assets of some type, which could include monetary instruments restricted to not be able to leave the country, should not be able to vote either. This would all be purely voluntary—you can work for the government, or own only fungible liquid assets. But then you just can’t vote. Naturally, those with more children, or grandchildren, who otherwise are eligible to vote would be given substantial additional voting power, as well.

Beyond stripping the franchise from the underclass, we would need to combat all the habits of thought that constitute the worldview of the underclass, whose ultimate source and cause is the dominant cultural Marxists in the classes above them, who alone have caused all this human suffering. Therefore, the necessary first step is crushing the Left and destroying their power, totally erasing the false gods of “emancipation” and of imaginary equality of ability. That won’t be easy or pleasant, but as the recent Brett Kavanaugh circus showed us, the wars to come are emerging from the mist, no longer over the horizon. After that is successfully concluded, and the equivalent of denazification completed with the Left, we should rigorously re-impose moral judgments and enforce resulting standards, starting with the distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor. The former will get necessary support, with guardrails against moral hazard. The latter will be detoxed and made to work at hard manual labor, make-work if necessary. Any and all crime (which will not include “hate crimes” as a special category, and will most definitely not include wrong-thought, as the Yorkshire police would have it) will be punished severely and publicly, up to and including swift capital punishment (this book makes one realize the absolute need for it, whatever that odious little troll Jorge Bergoglio may say, and a little goes a long way). That’ll also take care of reintroducing reality as a guiding principle for the underclass, as well as personal responsibility, since lack of the latter will lead to, depending on its locus, rapid punishment or literal starvation.

So much for negative reinforcement. But there should be plenty of positive reinforcement, too. The goal here is to help members of the underclass flourish to the extent it is within their talents, not to simply make them orderly, secure, and productive. Excellent old-style education will be provided for free to the underclass, with early identification of the most deserving, who will be given all the education they can handle, in social capital-building subjects. (Other students found to be discouraging learning by others will be publicly whipped, solving that barrier to advancement.) Thereby, aspiration will also be brought back, and students will quickly grasp that aspirations can be made real. That’ll take care of people being ignorant and having a short time horizon. Rapid advancement in all areas of life will be possible for the talented, who will be rewarded by earning the best jobs in government (shades of Ottoman government service, or rather of much of high Muslim culture, though since that culture is very long gone, no more Muslims, from anywhere, or any other immigrants from other inferior cultures, except for maybe their rich and educated, will be allowed to enter Britain, at least until Islamic high culture rises again, which is entirely possible). Resources wasted on gender studies and a huge range of similar upper class stupidities and frivolities will be re-allocated to rebuild the infrastructure of the no-longer underclass (and purveyors of and participants in those stupidities and frivolities will find productive labor or starve).

Certainly, when all this is accomplished, along with much more along the same lines, there will still be poor people, because some people just don’t have talents that are worth anything to anyone else, and when you produce nothing, you earn nothing. But they won’t be degraded poor people, and a society run on sane and just principles will make adequate provisions for deserving poor people. Justice, after all, is giving to each his due (whatever creepy John Rawls may have imagined), and this reworked society will have justice in abundance. What it won’t have is an underclass. You’re welcome.