2021 will be the twentieth anniversary of our endless, pointless war in Afghanistan, and 2023 the twentieth anniversary of our endless, pointless war in Iraq. This book, the ideas in which predate both those wars, and in fact date back to shortly after we lost the Vietnam War, says that our military should train to fight a new kind of warfare, fourth-generation warfare, in order to win victory. What struck me most about this book is that it’s not all that new. It’s still a worthwhile short read, but you will get more out of it if you read it along with a far more insightful work—Carl Schmitt’s 1962 Theory of the Partisan.

In Lind’s terminology, fourth-generation warfare, which we will define more precisely in a moment, is basically warfare by a state against non-state opponents. You might think that’s exactly what we do in Afghanistan and Iraq, and as far as I can tell, it is. Lind’s claim, however, is not that we need to be prepared to fight a fourth-generation, guerilla-type war. His claim rather is that our military fights fourth-generation war, including current wars in the Middle East, with second-generation methods, decades after it should have known better. His book’s target, therefore, appears to be higher-ranking military officers who have flexibility to change local approaches to American warfare.

You Should Subscribe. It’s Free!

You can subscribe to writings published in The Worthy House. In these days of massive censorship, this is wise, even if you normally consume The Worthy House on some other platform.

If you subscribe will get a notification of all new writings by email. You will get no spam, of course. And we do not and will not solicit you; we neither need nor accept money.

Whether Lind’s claims are true, I am not qualified to evaluate. I have little knowledge of the nuts and bolts of modern military theory, and less of tactics or operations. I have several close family members in the military, but never served myself (though I may yet fight in the civil wars, and am still young enough to do so). Yes, I know a lot about military history, but that is a different thing. Perhaps as a result, I’m still not quite sure what to think of this book. People keep recommending it to me, and much of it seems to offer useful insights into how the United States should conduct itself in wars in the Third World. I’m just not sure any of those insights are unknown to its target audience.

Lind is not a soldier either. He developed the basic ideas in this book, more extensive treatments of which elsewhere he points the reader to, with a small group of military officers, around 1980. I wasn’t paying attention then, but I do remember that in the late 1980s, and in the run-up to the First Gulf War, American military thought, and the public’s thoughts about America being involved in wars, revolved wholly around the trauma of America losing the Vietnam War. We now remember the First Gulf War, 1991, as a triumph, but that conclusion was far from foregone—many voices at the time argued that the war would be another Vietnam. Nonetheless, it broke the in-retrospect salutary feeling that perhaps America should not over-extend itself, and in the decades since America has, to no benefit for us, now become a fully imperial power, actively fighting in places that serve no purpose for the American people as a whole.

History and politics are not Lind’s concern, however. His concern is tactical success in places where America is fighting. In Lind’s frame, second-generation warfare, characterized by the French after World War I, emphasizes rigid order, heavy use of artillery (and later, air power), and execution of pre-set rules and “school solutions.” Lind says this is how the United States still largely fights today. Third-generation warfare, exemplified by the Germans in World War II, is non-linear, emphasizing speed and tempo rather than firepower, and encouraging flexibility and initiative, deemphasizing centralized decision making. You would think all state militaries would have adopted third-generation warfare by this point, given that it seems to succeed almost all the time, if other factors are equal, but Lind says this is wrong, and because militaries adore a “culture of order,” most remain essentially second generation.

States fighting each other today is some combination of second- and third-generation warfare. Fourth-generation warfare, on the other hand, involves a more disparate hybrid—large armies designed for second-generation warfare attempting to occupy territory where there is no operating state military and the inhabitants are ethnically, religiously, and politically hostile. Lind calls militarized inhabitants in opposition “non-state forces,” but a much better term is the older “partisans.” Contrary to what Lind implies, the task of a state military fighting partisans is not a new problem; Julius Caesar faced it. Even the specific challenge that Lind is trying to address, a large, highly-trained, centralized state army fighting what amounts to a guerilla insurgency, is old—its modern incarnation was probably first seen in the Peninsular War. In any case, Lind thinks we’re too often doing it wrong.

Lind ascribes the hostility of the locals in fourth-generation warfare to a “crisis of the legitimacy of the state.” The state in question is not us, the attackers, but the state that might otherwise claim the loyalty of partisans. He means the partisans have a primary loyalty to something other than the state—most often ethnicity or religion—so that even if the state is defeated by the partisans’ enemies, fourth-generation warfare continues in a way second-generation or third-generation warfare would not. He seems to think this is an odd condition, but the natural condition of most societies is that those things are very important, and often more important to citizens than the state. (America was long an exception, although, as we saw this past summer, our elites are doing their best to encourage racial violence, which will not end well.) It is therefore only natural when any state is destroyed that the new organizing principle is something that precedes the state, so I’m not sure that dressing this basic fact up in fancy language adds anything for the reader, not to mention that if recent history is any guide, mostly this “crisis” is caused by the United States destroying the functioning state that had existed.

Regardless, Lind’s main practical point is that fourth-generation warfare should be light infantry warfare. Not in the sense that term is used in today’s military, meaning mechanized infantry without armored vehicles, but more like Roger’s Rangers or other successful small, fast-moving, lightweight forces that live off the land, such as the Selous Scouts (not an example Lind gives, and there are other gaps, such as nothing about drones and similar technology, and how those might affect both light infantry and partisans). For such units, in essence guerillas in their own right, mental attitude, of flexibility, toughness, and creativity, is even more important than speed of movement, and they emphasize basic skills often lost in second- and third-generation warfare, from land navigation to physical fitness to broad weapons proficiency.

The book alternates specific advice with short fictional vignettes showing how the principles should be applied in a conflict (a nameless Middle Eastern war). About half the discussion concerns light infantry in all its practical aspects. The rest addresses other topics Lind thinks tied to light infantry success. He points out that the less stable a conquered state, the harder the fourth-generation challenge. Thus, keeping a defeated state’s military and bureaucracy largely or wholly in place is essential to keeping the challenge manageable. This only applies where there is a defeated state (and is something America failed to do in Iraq—remember the odious Paul Bremer?). Collapsed societies (Somalia, Afghanistan) or an American civil war are therefore likely to be a much greater fourth-generation challenge than a place like Iraq. Lind recommends wide use of bribes, with zero track being kept of them—but that was not a success in Afghanistan, where the wily locals simply took our money and laughed. He suggests offering green cards to those who help us—but we have a long history of higher-ups lying to and betraying the locals who help us based on the promises of our men on the ground, and this has continued in Iraq and Afghanistan. He recommends building bridges with the press—but ignores that today’s monolithic press corps is just as ideological as any partisan, so only left-wing bridges will have any chance of being successful, and those are rarer than hens’ teeth in wars, at least until the United States invades Poland to run a rainbow flag up the flagpole in front of Parliament. So yes, I’m sure using light infantry makes more sense than driving Abrams tanks through the streets and shooting 120mm shells at every swarthy man in a burnoose who pops off a shot with an AK. But I’m not sure this book adds much to common sense.

Underlying these practical points is a key philosophical point—that just because the American military has the physical ability to do something that appears tactically useful does not mean that doing it will advance us toward victory. Instead, it will frequently erode what Lind calls our “moral” position, which he says is crucially important for victory. This is an unfortunate choice of words, because Lind uses “moral” in two entirely distinct senses. We might call these “spiritual morals” and “practical morals.” Lind never distinguishes between the two, which makes what he is specifically recommending sometimes unclear. In all cases, though, Lind uses “moral” arguments to call for measured, limited approaches to partisan warfare, rather than a war of annihilation.

The first use of “moral” is its traditional use in America, meaning “not sinful under Christian principles.” True, nobody would openly define “moral” that way today—instead, there would be mention of “ethics,” and John Rawls would come up, and there would be meandering talk of justice, unmoored from any first principles. But what Lind means, and what others mean when they talk about the “morality” of war, is what has often constrained Western powers in wars in the Third World—the desire to not get wrong with Jesus Christ. That may be the desire of the country’s leaders, but more often is their desire for public opinion, still largely tied to Christian morality, to not turn against them. Actions that are not “moral” in this sense do not erode our tactical position, however, so strictly speaking they should be ignored by Lind in his analysis, yet they keep creeping in.

The other sense of “moral” that Lind uses is “not offensive to the locals.” For example, in a culture that emphasizes pride and honor, humiliating men, especially by manhandling their women, is a very bad idea, and very counterproductive, in that it stiffens the spine of the locals and provides a spur to retributive violence. His analysis is somewhat superficial; he seems to think that “bullying” is always counterproductive, although this is largely an artefact of Western, specifically English, notions of “fair play,” not something particularly resonant in many other cultures, which did not read Tom Brown’s School Days, and are happy to gravitate to the strong horse. Actually, Lind is perfectly well aware that it is possible to utterly crush partisan movements, especially in cities, by bullying on a mass scale. He calls this the “Hama model,” after Hafez al-Assad’s successful repression of Sunni Muslims in Hama in 1982, killing thousands—and turning the city into a model of stability for decades. You have to go all the way, though (and America can’t, because of the first sense of “moral”), but if you don’t, offending the locals, whipping them up against you, most definitely can have a tactical impact on victory. Ask the British in the First Afghan War.

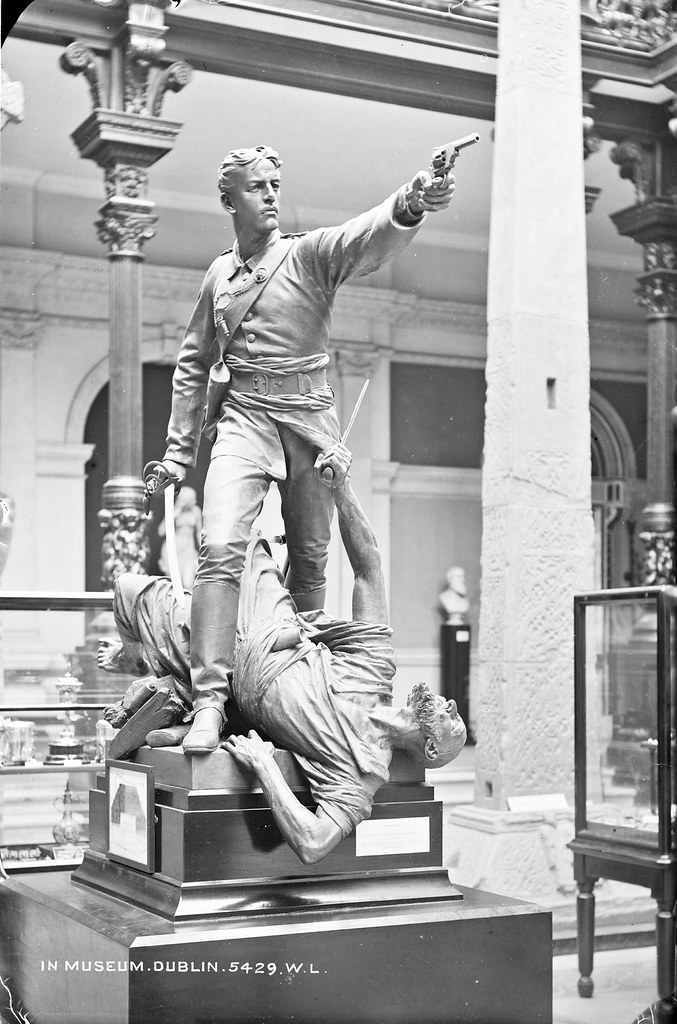

On a side note, speaking of the British and Afghanistan, I happened to see a picture the other day of a statue of the last stand of one Lieutenant Walter Hamilton VC, who died in this type of violence, in 1879, in the Second Afghan War. He had earlier earned the Victoria Cross, and he and several dozen men under his command died to the last man defending the British representative to the Afghans, when attacked in Kabul by mutinous Afghan troops. Whether this was due to what Lind would call a “moral” offense I am not sure. What I am sure of is that our society no longer honors a man such as Hamilton. Can you imagine a statue like this one being presented to today’s young as something to admire? No, you can’t. But you can be sure they see plenty of (talent-free) statues of the fentanyl-addled scumbag George Floyd. A society gets more of what it honors.

Staying for a little in the past, because it’s more pleasant there, viewing Lind through the lens of the classic Carl Schmitt work on partisans can help us with understandings missing in Lind. Schmitt’s view is that partisan warfare, that is, irregular warfare against states, can only exist if there is regular warfare. By this he means not war among states, but warfare with rules, rules designed to implement “morals” in both senses Lind uses. This distinguishes partisan warfare against Rome, where there were no rules, from that against a nineteenth-century European state, where there were—a key distinction lost in Lind. It is this binding by rules that makes fourth-generation warfare so challenging for a modern Western state.

Schmitt does not view partisans as so much a manifestation of a tactical problem, as Lind does, but of total enmity, a crucial focus of Schmitt in many of his writings. Partisan warfare in the modern world is ideological, which means it is not limited in the way that warfare directed to political ends traditionally is, in that when those ends are achieved the fighting stops short of the total destruction of one side. At the same time, the new rules of warfare “bracket” the partisan, making him someone not entitled to the protection of the rules, a mere bandit. Both these mean that the partisan fights more viciously, and the reaction is equally vicious, in an upward, or downward, spiral. For Schmitt, enmity is natural and unavoidable, but partisan conflict removes limits that can otherwise be placed on enmity, creating “absolute enmity,” leading to wars of annihilation. This suggests why the measured and limited fourth-generation tactics Lind lays out as common sense are difficult to implement in practice—it is not just stupidity and sclerosis, as Lind implies.

Schmitt gives as example the French experience in Algeria, where the French general Raoul Salan was unable to break the Algerian insurgency, leading Salan himself to engage in terrorism and assassination on French soil (or rather in France proper, since Algeria was just as much French soil). I doubt that Lind’s advice would have made defeating the Algerian partisans possible. Schmitt was not optimistic about fourth-generation war—he saw that with modern technology, the erosion of strong social structures, and the cross-border nature of partisans, they could be much stronger than in the nineteenth century. Lind offers no solutions for these problems.

I cannot tell if the ideas in this book have been implemented to any relevant degree by the American military. If they have, perhaps they have helped the United States on a tactical and operational level. However, if we are incompetent in the larger strategic realm, better tactics and operations will not save us. And we are nothing if not incompetent in the strategic realm.

Lind doesn’t think that our goal should be “to remake other societies and cultures.” But that, not benefiting the United States and its people, has been the entire United States strategic project for the past thirty years, on a military and every other level. When we went to war in Iraq, not for oil but to serve George W. Bush’s insane idea that he could turn Iraq into a peaceful democracy, few conservatives thought what we were doing was giving leave to our rotten elites to, a few decades later, try to destroy countries like Poland and Hungary. The raison d’être of all outward-facing United States actions abroad is now to spread globohomo, the project of the Left, by any means necessary across the world to any country that is not on board with it and does not have the ability to resist. The American elite sponsors under our flag, and funds, weevils who travel the world, flying rainbow flags and dispensing pallets of cash, the latter dished out to small minorities eager to corrupt and destroy the societies in which they live—and to create astroturf NGOs who manipulate English-language media. (A very small example of this received rare publicity last week when “stimulus” checks were tied to ten million dollars going to force Pakistan to progress toward “gender equality.”) If this doesn’t work to destroy the culture of countries that won’t get on board with globohomo, America stands ready to implement regime change through “color revolutions,” and, no doubt, with sub rosa military force. This, not fourth-generation warfare against Islamists, and not pushing back against Chinese hegemony, is the real strategic focus of America. It’s not pretty.

Of course, our military is by no means exempt from this corruption. It is, as far as I can tell, completely rotten at the head, and several levels below, although many enlisted men, and many (but far from all) lower-ranking officers are opposed to the Left’s project. The bad news is that if we ever have to fight anybody but partisans, such as the Chinese, it’s going to go poorly—although perhaps leading to desirable regime change here, if our ruling classes are discredited as a result. The good news is that if our illegitimate soon-to-be President, Joe Biden, ever tries to use the military to impose the Left’s will on our own soil, that will also go poorly. I guess it’s a race to see which comes first. Happy Inauguration Day!

You Should Subscribe. It’s Free!

You can subscribe to writings published in The Worthy House. In these days of massive censorship, this is wise, even if you normally consume The Worthy House on some other platform.

If you subscribe will get a notification of all new writings by email. You will get no spam, of course. And we do not and will not solicit you; we neither need nor accept money.