Gun control is one of those few issues where there are zero good arguments on one side. Almost anyone who supports gun control is ignorant. Not a malicious ignorance, necessarily—more of an ignorance born of a love of moral preening. On the other hand, it is true that a few gun control supporters are not ignorant, but rather liars, who understand that gun control arguments make no sense on any level, factual or logical, but use them as a cover to achieve their end of keeping law-abiding citizens from having guns, in order to achieve their greater end of more government control of the citizenry. But mostly it’s ignorance—essentially every supporter of gun control knows nothing about guns, nothing about the insane and criminals, and nothing about history. It’s for that latter lack that this book is an excellent corrective, even though almost certainly no “gun control supporter,” a tautology for “invincibly ignorant person,” will read it. That’s too bad.

Gun control is one of those few issues where there are zero good arguments on one side. Almost anyone who supports gun control is ignorant. Not a malicious ignorance, necessarily—more of an ignorance born of a love of moral preening. On the other hand, it is true that a few gun control supporters are not ignorant, but rather liars, who understand that gun control arguments make no sense on any level, factual or logical, but use them as a cover to achieve their end of keeping law-abiding citizens from having guns, in order to achieve their greater end of more government control of the citizenry. But mostly it’s ignorance—essentially every supporter of gun control knows nothing about guns, nothing about the insane and criminals, and nothing about history. It’s for that latter lack that this book is an excellent corrective, even though almost certainly no “gun control supporter,” a tautology for “invincibly ignorant person,” will read it. That’s too bad.

A reasonable initial reaction to this book is that it’s a prima facie violation of Godwin’s Law: “As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches one.” But that reasonable reaction would reject the possibility of any apt comparison being made on any issue to the actions of the Nazis. In this case, that would be a mistake. Unfortunately, Godwin’s Law probably does limit the usability of this book in some actual discussions—but fortunately not in all.

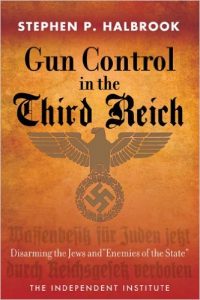

Stephen Halbrook, one of the world’s leading scholars on gun rights, has done a great deal of original research to buttress the conclusions and arguments of this book. Those conclusions are, in essence, that (a) gun control in Germany, beginning shortly after World War One and in part dictated by the Allies, was aggressively phrased but little enforced; (b) as disorder increased and developed a more political component, gun control became more loosely phrased but much more aggressively enforced; (c) such enforcement was in practice done only against already law-abiding citizens and involved careful tracking of any citizen owning a gun; and (d) even though the danger was recognized, such tracking was immediately used by the Nazis upon their accession to power to destroy any chance of an armed German citizenry.

Dr. Halbrook parses many German legal documents and court cases, most presumably never before available in English, to prove his points. He voluminously footnotes his work, and he cites to various scholars opposed to his (earlier) legal articles on this and related topics, encouraging the reader to obtain opposing views (probably because they’re so weak, but you can’t blame him for that). As Dr. Halbrook shows, most of the practical consequences of German gun control, other than greasing the Nazi rise to and consolidation of power, were exactly what you’d expect: only law-abiding citizens lost their guns (which, when criminals continued to use guns, was used as an argument for further restricting law-abiding citizens, just as in the United States, until the recent reversal in fortune for gun rights in the US).

The conclusion is not, of course, that 2015 America is 1930s Germany. Not only are gun rights here continuing their fast rise, and the gun grabber movement on the ropes, if not knocked out, but America’s history, culture and Constitution all are very different. Of course, there is a powerful, vocal, tiny minority in America who have the same ends in mind with respect to guns as the Nazis, even if not the same general ends in mind (although when your mind runs in the same track, you tend to end up in the same place). And vigilance against them is and will be constantly necessary. But on this issue, past is not prologue, in all likelihood.

Various other items pop off the page. For example, Oskar Schindler, of Schindler’s List fame, made sure that his Jewish workers received guns and training, a fact of course omitted in Spielberg’s film. Another fascinating fact found in the book is how few guns there were in Germany in private hands, yet the extreme lengths the Nazis went to confiscate them. Most guns were, of course, low-capacity pistols or bolt- or single-shot rifles on a hunting or World War One military pattern. In 1933, Wilhelm Frick, the Reich minister of the interior, complained to Hermann Goring that in one month, 17,000 pistols were imported, “ten times the average import of the preceding three months.” You can extrapolate from that that around 20,000 pistols were imported a year into Germany (although that of course excludes domestic production). Compare that with the roughly 25 million guns sold in the US in 2014 alone and you can conclude that the societies are very different. What the meaning of that difference is may not be clear (it is not homicide rates, which are quite low for the US relative to most of the world, and which are just as low as even Western Europe when adjusted for the demographics of 90% of the US homicides.) But, doubtless, one conclusion should be that the process and result of any civil unrest or government authoritarianism in the United States would be quite different than it was in Germany, which is as it should be.

Dr. Halbrook is very cautious in his conclusions as applied to the modern world. His only real conclusion in that regard is “But an armed populace with a political culture of hallowed constitutional and natural rights that they are motivated to fight for is less likely to fall under the sway of tyranny, and if they do, they are more likely to offer armed resistance. A disarmed populace that is taught that it has no rights other than what the government decrees as positive law is obviously more susceptible to totalitarian rule and is less able to resist oppression.” No doubt.