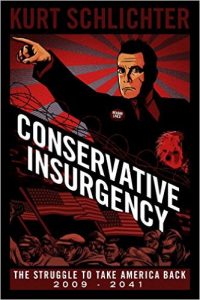

Conservative Insurgency is that rare animal: an optimistic look at the future of America through a conservative lens. Framed as a fictitious oral history (think Studs Terkel) from 2041, when a form of conservatism has come to dominate essentially all areas of American life, the book largely succeeds in its goal of showing how such a consummation, devoutly to be wished, might come about—through a decentralized, self-organizing strategy: an insurgency (hence the title).

Conservative Insurgency is that rare animal: an optimistic look at the future of America through a conservative lens. Framed as a fictitious oral history (think Studs Terkel) from 2041, when a form of conservatism has come to dominate essentially all areas of American life, the book largely succeeds in its goal of showing how such a consummation, devoutly to be wished, might come about—through a decentralized, self-organizing strategy: an insurgency (hence the title).

First, though, it’s important to understand that Schlichter’s triumphant future conservatism is purely that of one strain of modern conservatism—what might be called Agnostic Pragmatic Libertarianism. There is apparently no room in the future public square for traditional religious believers or for social conservatives, though they may of course express their opinions without the hatred and harassment that is already de rigeur for such poor Neanderthals in Anno Domini 2015. Russell Kirk will not be widely honored in this future society. Rod Dreher, do not call your office. In fact, intellectual conservatives in the Burkean tradition are totally missing, replaced by simple calls for less government and avatars of Elon Musk and Peter Thiel. But perhaps that’s reality, not prejudice.

Schlichter does not address alienation, community, or the roots of American order. If you are looking for a considered evaluation of Robert Nisbet or Albert Jay Nock, you will not find it here. But you will find is a pragmatic and programmatic path to conservative victory, through using the vicious tactics invented by the Left to achieve the goals of the Right. And if you want a regeneration of community, first Leviathan must be pruned or slain, which could allow spontaneous community regeneration, if it can happen at this late date.

Naturally, Schlichter has no use either for “establishment” Republicans, who have already proved their worthlessness by getting us to where we are now, so no loss there. Conversely, Schlichter generally approves of Tea Party types (while acknowledging that libels have made that name toxic), but only if they leave their social conservatism and religiosity at home.

What Schlichter predicts is likely the best that American can hope for. An analogy might be made (which Schlichter does not) to the Rome of 44 B.C. As pointed out in Roger Kimball’s review in the New Criterion of Barry Strauss’s book The Death of Caesar, those who create a revolution in the hope the result will be a return to the days of yore are doomed to disappointment. Societies and ages have their own momentum, and the best hope is to channel the rushing stream to clean the Augean stables, and then carve out the valleys that you want, not those your enemies want. But the stream will not return to its source. So in that sense Schlichter’s practical program is ideal, for its recognition of reality.

Schlichter repeatedly notes, and expresses hesitation, at recommending that conservatives use the nasty, anti-democratic tools perfected by liberals over the past four decades (such as personalizing and freezing individual targets, in the Alinskyite manner.) He is keenly aware of the tension between recommending these methods and being conservative. For example, conservatives frequently want more federalism in the US system, and using the power of the federal government is inherently anti-federalist. But Schlichter realizes that conservatives have to use levers of power as they are, not as we would with them to be, to achieve their goals. There is probably no return to the old days of truly limited government.

So, for example, the book specifically recommends “raw exercise of unrestrained power.” Among many other such actions, Supreme Court members who legislate from the bench (i.e., all liberal members) will be impeached and removed, to be replaced with conservative judges. And Schlichter realizes this will be an all-out war, even with some incidents of violence, and liberals will use even more the tools they use now, such as criminal indictments for political actions (think Rick Perry); criminal indictments on bogus grounds to intimidate conservatives (think Dennis Hastert); and straight-out Big Lie tactics (think the simply false accusations of racist behavior by Tea Party demonstrators). Schlichter would punch back twice as hard with the same tactics. As Sean Connery said in The Untouchables: “What are you prepared to do?”

Liberals would howl to have their own tactics used against them. They are always quick to remind conservatives that conservatism traditionally means not using radical tactics, so conservatives should simply sit down and shut up. In the modern liberal construct, almost every political decision is heads-I-win-tails-you-lose. Anything liberals do is permanent; anything conservatives do is transitory and illegitimate.

If liberals control the legislature in a state, their political position prevails over conservatives. But if liberals do not control the state legislature, they get the state judiciary to overrule the legislature. If they cannot do that, they get the federal legislature, Congress, to overrule the conservative state legislative position. If that fails, they get the federal judiciary to do so. Liberals only have to control one of four political levels to win a political issue (even though only two are supposed to legislate, liberals have successfully transformed the courts into hyperactive legislative bodies). On the other hand, conservatives by temperament and philosophy don’t like to pull the same tricks. If they lose at the state level, they tend to accept that. Rarely would they force a federal legislative overrule of state decisions, and if they do liberals harp on the contradictions to their philosophy (using their total dominance of the news-setting media). And conservatives would rarely legislate from the bench—only a tiny fraction of conservatives, for example, want the Supreme Court to declare abortion illegal, even though a powerful argument exists that the Constitution forbids it (as deprivation of life without due process of law)—they just want individual states to decide, and would abide by that decision. But for liberals, the end is the only thing that matters, and controlling any of multiple levers of power gets the result they want. All the time liberals are aided by total domination of the media and popular culture. Conservatives have to have a syzygy to achieve anything. This may be principled on the part of conservatives, but in the modern world, it is suicide.

Unfortunately, even if conservatives were successful in following the Schlichter program, our society would likely end up polarized, like a Greek city-state, endlessly feuding between oligarchs and democrats, with ultimately fatal consequences for the society. But since the alternative is giving in to the liberal program of destruction of America right now, Schlichter’s approach is probably the right one.

My biggest criticism is that Schlichter recognizes that conservatives can never win unless they conquer the news media and the cultural media (movies, US Weekly, etc.) But Schlichter is overly optimistic, to the point of being facile, about the chances of this happening. Unfortunately, the hope that young people will enter these domains while actively concealing their political beliefs, ultimately reforming them from within, is certainly a chimera. (And he ignores that most cultural media is pitched at low-information voters and people with lots of emotion and no brain cells, who are less likely to respond positively to rational conservative messages.) Schlichter has to recommend something, but that’s not realistic, and if it were to start happening, the Right Sort Of People would use every means at their disposal to end the invasion.

Personally, I’m not an optimist. More likely than Schlichter’s vision, or the highly optimistic vision of Michael Lotus and James C. Bennett in America 3.0 (which has more policy suggestions and less bare-knuckle politics), is permanent stagnation or, alternatively, violence that creates a fundamental transformation that is unfortunately unlikely to lead to anything conservative would like. Perhaps if there were an external shock (Asteroid! Pandemic! ISIS!) the resultant disruption would allow conservatives to both seize the levers of power and smash the liberals who maintain an iron grip on the news and cultural media. Short of that, success seems unlikely, and there is no historical example of a society regenerating itself. But each age is new, and maybe it is possible.

In practice even small steps pushing back against liberal dominance would be violent opposed. Let’s say that conservatives today tried to set up a crowdfunding platform to compete with GoFundMe, one that allowed campaigns to support persecuted supporters of traditional marriage and to purchase legal firearms-related materials. Such a platform would be immediately demonized by the media, followed by an organized social media firestorm abetted by all the leading lights of the tech industry, followed closely by federal investigations of alleged money laundering and other financial crimes, using open-ended and vague laws susceptible of any interpretation. The site would quickly be shut down, its founders ruined by legal fees and likely in jail, having taking a three-year plea deal in lieu of facing a life sentence if convicted of violating opaque laws nobody has ever heard of that were not intended to do anything like that what they are used for.

The only possible end results are three: knuckling under; bare knuckle politics; and political violence. Schlichter recommends politics. Something has to be done, and this book is probably precisely right what on what that should be, given the limitations of reality.