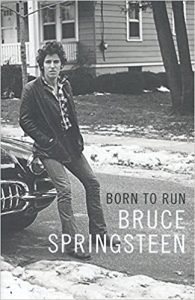

I’ve always liked Bruce Springsteen, but never knew much about him beyond what could be read in the news. His autobiography, Born to Run, tells everything a reasonable reader could want. It’s not a tell-all, certainly—while Springsteen honestly relates his life, including quite a bit of self-criticism, he says explicitly he has not told the reader everything. Still, the reader learns a lot, and for someone like me not sentient in the 1970s, in particular, the book draws a vivid picture of a particular unique time.

I’ve always liked Bruce Springsteen, but never knew much about him beyond what could be read in the news. His autobiography, Born to Run, tells everything a reasonable reader could want. It’s not a tell-all, certainly—while Springsteen honestly relates his life, including quite a bit of self-criticism, he says explicitly he has not told the reader everything. Still, the reader learns a lot, and for someone like me not sentient in the 1970s, in particular, the book draws a vivid picture of a particular unique time.

The only surprise, really, is why, given his views repeatedly expressed in this book, Springsteen is not a populist conservative rather than a tool of the Left, used to advance interests on every front inimical to what Springsteen believes. We are never given the answer, though I have thoughts of my own below. But this is primarily a book about family and personal vision, even more than about rock music, and much more than about politics, so we should not over-analyze or turn the focus too far from what the author himself focuses on. Not everything in life has to be about politics.

Springsteen wrote this book completely by himself, and reads the audiobook as well (which is how I absorbed the book). Lack of a ghostwriter shows, not in a negative way, but in the short, conversational, stream-of-consciousness chapters; the many asides to the reader; the numerous full-hearted exclamations in ALL CAPS; and in his obvious boundless joy with his life, with all its challenges and heartache.

Certainly rock music plays big role and frames much of the book. But as I say, the book itself is mostly about family. Primarily, this means blood family, but it also means Springsteen’s friends, of whom the most important are the late Clarence Clemons, saxophonist, and Steven Van Zandt, guitarist. But Springsteen, never explicitly but most definitely in practice, draws a sharp line between his family and his companions. Family bookends the story, from Springsteen’s earliest memories of his childhood home to the last scene in the book, coming home at night on his motorcycle, thinking “how lucky I’ve been, how lucky I am.” And the dominant theme of his story, though not to the exclusion of other themes, is Springsteen’s troubled relationship with his father—never truly broken, but never truly good. His father was a difficult, distant man, whom Springsteen loved but who, in the old way, was emotionally detached, a defect exacerbated by various character flaws and heavy drinking.

Beyond his family stories, though, the book is filled with innumerable evocative and poignant short stories about the people and times that have filled the author’s life. In Springsteen’s first band, the Castiles, the drummer, Bart Haynes, could play well, but could not play the simple beat to “Wipe Out.” In just a few sentences, Springsteen humorously draws a picture of how, every show, competing drummers in the crowd would goad Haynes to try to play the song, until, giving in, he would try, and “fail, time and time again.” In the next paragraph: “Bart would shortly give up the sticks for good and join the Marines. . . . In the days before his ship-out, he’d sit one last time at the drums, in his full dress blues, taking one final swing at ‘Wipe Out.’ He was killed in action by mortar fire in Quang Tri Province.”

Above family and politics, Springsteen’s detailed discussion of his own depression is, I think, particularly valuable to the reader, and to society. For many of us, the natural impulse is to think that a man as successful and rich as Springsteen, with a loving family, a secure and admired position in society, and the gift of doing what he loved best and was best at his whole life, couldn’t suffer from depression. The mostly forgotten turn-of-the-20th Century poet, Edwin Arlington Robinson, even wrote one of my favorite poems about this implicit belief most of us have about the rich and successful, which I read as a small child and have always remembered, I think to my benefit. In Richard Cory, the eponymous hero is a wealthy, popular man, perhaps not dissimilar to Springsteen. The short poem ends: “So on we worked, and waited for the light, / And went without the meat, and cursed the bread; / And Richard Cory, one calm summer night, / Went home and put a bullet through his head.” Springsteen’s invaluable service in this book is to show that depression can happen to anyone, and that there is real help available, which has made all the difference to him.

I suppose every person’s presentation of himself to others can never be truly trusted, but the reader feels like he gets the measure of Springsteen from his words. He is a man of discipline, of self-control, of self-help. He is also a man of community, keenly interested in helping others—but only if and to the extent they help themselves, if they are able. Thus, as to discipline and self-control, he stayed totally clear of any drugs or alcohol until his twenties, and then only in moderation when he discovered he was, unlike his father, a “happy drunk.” “The dumb and destructive [stuff] that I saw done in the name of people trying to ‘let it all hang out,’ to be ‘free,’ was legion. . . . I was never gonna get a first-class ticket to see God the easy way on the Tim Leary clown train.” “I was always proud but also embarrassed by being so in control. Somewhere I intuited that if I crossed that line it would bring more pain than relief. This was just the shape of my soul. I never cared for any kind of out-of-control ‘stonedness’ around me.” As to self-help, Springsteen for decades has maintained a constant focus, never resting on his laurels. This boils down to a phrase he uses variants of repeatedly: “You can’t tell people anything; you’ve got to show ‘em.” A lot of people with his level of success would have coasted on reputation and aura; not him. Self-help doesn’t just apply to him, either—he describes his band, in every incarnation, as a “benevolent dictatorship,” where there is no democracy. Rather, he sets boundaries to both help his bandmates and to allow him, himself, to achieve the goals he has set for his life.

As to helping others, Springsteen is very much working class, deep in his bones. His background and feelings are not lower class, an important distinction. His family worked, and worked hard. As Joan Williams diagnoses (with flaws) in White Working Class, the working class doesn’t tend to want handouts (something they ascribe to the poor and resent them for it)—they want a fair deal, and they haven’t gotten it for decades. Thus, Springsteen says, “I wanted to understand. What were the social forces that held my parents’ lives in check? Why was it so hard? In my search I would blur the lines between the personal and psychological factors that made my father’s life so difficult and the political issues that kept a tight clamp on working-class lives across the United States. . . . A dignified, decent living is not too much to ask. Where you take it from there is up to you but that much should be a birthright.” He doesn’t look at this through the lens of modern social science, or politics, but with a visceral feeling bred of family and upbringing. And he’s right.

Springsteen is, of course, rich. He knows everyone knows it, too—he jokes about taking his private plane to dental appointments. Still, he’s viewed, to the extent he’s viewed politically, as a man of the Left. He was a prominent supporter of Hillary Clinton, very much not a believable champion of the working class. This seems like a contradiction, and maybe it is. But Springsteen is a smart man. I think, reading between the lines somewhat, that much of Springsteen hewing to the Democratic Party is that he perceives it to be more interested in equal racial treatment, an important and visceral concern to him. From his New Jersey background of frequent social contact with working class black people similar to his family, with casual racism still common and unremarked, to later racism directed at his black bandmates, opposition to racism is clearly important to Springsteen, and he (with some justice) believes that the Democratic Party is part of the solution. I think that’s simplistic and more true of the old Democratic Party, not the modern Left, but this book is about Springsteen, not me. (A book about me, unfortunately, would sell fewer copies.)

Still, he fits poorly in the modern American Left, with its focus on emancipation and unalloyed liberty unaccountable to any other person. “By 1977, in true American fashion, I’d escaped the shackles of birth, personal history, and, finally, place, but something wasn’t right. Rather than exhilaration, I felt unease. I sensed there was a great difference between unfettered personal license and real freedom.” Similarly, he in many ways exemplifies Edmund Burke’s view of society as “a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.” Springsteen summarizes his life, “I work to be an ancestor. I hope my summation will be written by my sons and daughter, with our family’s help, and their sons and daughters with their guidance. . . . [T]his kind of story has no end. It is simply told in your own blood until it passed along to be told in the blood of those you love, who inherit it.” All these are conservative sentiments—they fit no better with the neoliberal Hillary Clinton than with the corporate wing of the Republican Party, but they fit very well with Steve Bannon.

And I doubt Springsteen has much truck with “racial justice,” a phrase made meaningless by its lack of content and universal applicability to anything a speaker doesn’t like that is tangentially related to race. So he doesn’t mention, where others would, the current buzzword in the music world, “cultural appropriation,” and I’d guess he has nothing but contempt for it. To Springsteen, music is close to a powerful and near-sacred thing, but it originates from many places and many people, whose work is made new by the work of others. Just as he would reject the idea that rock music is not largely based on black music and black musicians, he would reject the idea that there is anything wrong with white people participating in, building on, and enjoying that music, as mere entertainment or as more, without focusing on its origins or development. The idea that he, a white man, should somehow apologize for his musical roots, I would guess, strikes him as both strange and offensive.

Conservatives too often ignore or denigrate rock music, which is often culturally nothing else than the popular music that exists in every age, really no different in its Springsteen incarnation from, say, medieval folk music. And its higher practitioners can be more—not just Springsteen, but, for example, Bob Dylan. In his recent Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Dylan showed much of the same arc of musical development as Springsteen, beginning with an epiphany (seeing Elvis for Springsteen; Buddy Holly for Dylan). And like Dylan, Springsteen has a religious sensibility (which frequently crops up in this book, including the reciting of the Lord’s Prayer near the end). Both derive their art from the human experience—Dylan, as he said in his Nobel acceptance speech, largely from the classics of literature; Springsteen from his own life. As with great literature, great music, popular or not, speaks to and expands the soul. You may not find Springsteen’s music to your liking, but we should all be grateful that he has enriched the American experience.