This may be the best “how to” book I have ever read, at least for manual work. Yes, I haven’t even started raising chickens (yet), so my base of knowledge for that praise is small. And yes, the book I read before this was the not-good “Keeping Chickens With Ashley English,” so after that, anything would seem good. But for a combination of clarity, useful information, complete coverage, and a coherent but rational philosophy, I don’t think you can beat this book.

This may be the best “how to” book I have ever read, at least for manual work. Yes, I haven’t even started raising chickens (yet), so my base of knowledge for that praise is small. And yes, the book I read before this was the not-good “Keeping Chickens With Ashley English,” so after that, anything would seem good. But for a combination of clarity, useful information, complete coverage, and a coherent but rational philosophy, I don’t think you can beat this book.

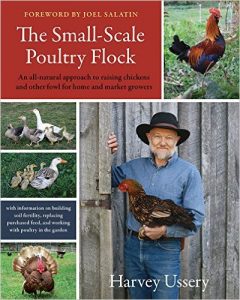

Ussery covers every aspect of making chicken raising productive to the owner, whether that person is a suburb dweller raising a few chickens or someone looking to make a profit from raising scores or hundreds of chickens. His focus is, as his title says, on an “all-natural” approach to doing so. In essence, his approach is a permaculture approach, though he doesn’t use that term, in which chickens are part of a complete cycle of life, from microbial life in the soil through humans. To that end, he advocates minimizing inputs from outside the farm (or yard), and rejects any technique that smacks of modern factory farming of chickens (which he rightly regards as an abomination). He covers the advantages and disadvantages of any given practice, and he makes clear recommendations in each instance.

From every page, Ussery’s practical experience shines through. And the book is extremely well written: no gaps, no infelicitous phrasing, no wasted words. Every minute spent reading this book is a minute well spent. I won’t go over the topics that Ussery covers, because other reviews do that and it’s easy enough to see on Amazon, but I don’t think he missed anything. You may not need everything Ussery covers—for example, you may not want to pursue some of the more “farm oriented” suggestions, like suspending beaver corpses in a container above chickens so they can eat the dropping maggots, but you don’t have to in order to be able to use this book. Whatever you do or plan to do, I am certain this book would be valuable to you.