I think Robert Louis Wilken is fantastic, but this is the weakest book of his that I have read. It is not that it is bad, or wrong, or stupid, in any way. It is that it falls into the genre I call “capsule history,” where many short chapters cover different happenings, and only a loose framework connects the chapters. The result is that a reader can learn something, or can even learn quite a bit, but the experience is too much like reading an encyclopedia. On the other hand, the book does consistently excel in one thing—communicating the loss suffered when Islam dominated or exterminated Christianity in its lands of first flourishing, from northern Africa to Mesopotamia. And if you’re looking for a factual overview of the first thousand years of Christianity, you’ll certainly get it here.

Throughout the book Wilken emphasizes several themes, so there is at least some integration among chapters. One is the centrality of community to Christians since the earliest years of Christianity, with consequent collective memory, often tied to tangible things. This was always an extremely demanding community, for centuries requiring public confession and rigorous penance. (That’s one reason why I always laugh with contempt when dullard American progressives claim that Jesus taught “inclusion and acceptance”—i.e., that Christianity doesn’t demand, and hasn’t always demanded, extremely specific actions and inactions. Although, among those demands is not having contempt for others, unfortunately for me). Moreover, Trinitarian theology also emphasized the communality of God, of which Christian communality was a reflection, creating a type of virtuous circle of community, reaching from Heaven to earth.

This ties to a second theme—the development of theology over time. Not new theology, but the deepening of thought and understanding on many topics. In his earlier The Spirit of Early Christian Thought, Wilken discusses the theology of the Trinity through this lens; here, the focus is on the development of the theology surrounding the simultaneous divine and human natures of Christ. I find this fascinating, just as I find Christian heresies extremely interesting. Yes, I know such things have no direct impact, necessarily, on an individual Christian’s life, and doubtless it is true that today we face problems and threats of immediate and great import, so it is important for comity and tactical advantage to gloss over divisions, and probably we should therefore not emphasize parsing confessional differences over the nature of Christ. Still, we shouldn’t lose sight of the importance of these matters—not only does this process of reasoning and subtle theology distinguish Christianity from all other religions, but that the best minds of the world spent generations struggling to reconcile revelation and reason about these matters should suggest, as a first cut, not that they were wasting their time, but that they were on to something, and we should pay attention.

Related to this second theme is a third, that intra-Christian disputes were the norm, rather than the exception, throughout the first thousand years of Christianity. This was true among theologians, and it was also true among the various centers of ecclesiastical power in the East (with the West, centered on Rome, also being involved during much of the period, with a gap after the decline of the Western Roman Empire). We are used to the idea that ongoing Christian disputes are rare, of minor importance, and either, for Protestants, decided by the individual, or for Catholics, ultimately decided by the Pope (at least until the past few years, when we have been disserved by Pope Francis). But this was most definitely not true of early Christianity, where significant disputes were common and usually settled by church councils. Some of those disputes were with currents of thought wholly outside mainstream Christianity, most notably Gnosticism. Others were within Christianity, but still were very substantial and led to lasting cracks. These included iconoclasm, which tore the Eastern Roman Empire apart more than once, as well as multiple arguments related to the vision of Christ’s nature. The latter led to whole groups regarding themselves as partially separate, including the Nestorian Christians, whose persecution by the Byzantines resulted, in part, in their cooperation with Muslim conquerors, whom they saw as heretics, not a new religion, a blind spot they recognized too late.

Beginning at the beginning, in Jerusalem, Wilken moves outward in time and space, first to the journeys of Paul, and thence to other areas of the Middle East to which Christianity spread, gradually increasing its hold on the population. Almost all of these areas are areas we think of as Muslim today. He also talks about numerous important individuals, some still famous today (Origen; Gregory of Nyssa; Athanasius; Maximus the Confessor) and many less famous, at least in the West (Shenoute, abbot of the giant White Monastery in Egypt; Mashtots, inventor of the Armenian alphabet, created as part of the work of conversion). He talks of persecutions (quoting, for example, from a variety of fascinating primary Roman sources involving interrogations of Christians; if this topic interests you, there is no better place to go than Wilken’s The Christians as the Romans Saw Them). He talks of church dependence on the state, and of its independence. He also discusses the tangled Christian relationship with the Jews—not the later, medieval one of pogroms, but one where Jews, who had large numbers in the Roman Empire, often persecuted Christians, and got the same and more in return.

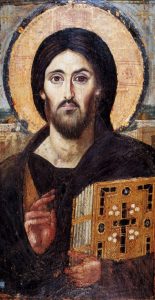

Naturally, Church councils, including Nicaea and Chalcedon, receive a lot of attention, both for the events themselves and for their subsequent ripples through history. Monasticism, a uniquely Christian practice, also gets a lot of ink, among other things for the leading role of women (Christianity is the only major religion that has always theologically treated women as not inferior to men, contrary to the common modern myth propagated by those who don’t actually know anything about Christianity.) Art and architecture, music and literature, are also extensively covered. Wilken includes a picture of the Christ Pantokrator painted in the sixth century and now in Saint Catherine’s Monastery, my favorite religious picture, which I have embedded here. Unfortunately, Saint Catherine’s is now located in Egypt, where Muslim literalists are on the march continuing the millennium-old Muslim cleansing of Christians from these lands, so it is at risk of destruction. But perhaps keeping such hordes at bay is what tungsten rods dropped from orbit are for. That’s just a stopgap–we probably need re-conversion of the Muslim lands, which is not impossible. If there is one thing that comes through clearly in this book, it’s that massive unanticipated changes in history are the norm, not the exception.

More mundane matters also crop up, such as the creation of recognizably modern hospitals by Basil of Caesarea, in the fourth century, far pre-dating Islam (hospitals are one of the many “inventions” often falsely claimed by Muslim apologists). Finally, as Islam crests over the historic Christian heartlands, Wilken turns more to the West being reborn, through the Carolingians, the spread of Christianity to the British Isles, and the groundwork for the Crusades being laid as Islam continued to choke the life out of Christians and their culture in the places conquered by the troops of Muhammad and his successors.

But all of these topics get covered in chapters of ten pages or less, and multiple topics are covered in each chapter. Again, this is inherent in the structure of capsule history, and in trying to cover a thousand years in a day. So, as I say, this is not a bad book, but it does not glitter like some of Wilken’s other works. My original plan was to use this as an audiobook to educate my older children in the car as I drove them to school. It’s not available as an audiobook, so I dropped the plan, and just read the book to myself. As an education device for teenagers, this book may be boring to them, and a little boring to me, but it communicates all the relevant information, so maybe I will make them read it after all! Communicate information is all it does, though, which should be enough, but somehow I was expecting more.