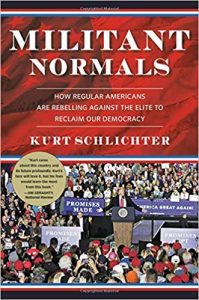

Militant Normals is an enjoyable read, a rollicking journey with the acid tongue of Kurt Schlichter as our tour leader. It is full of facts that are impossible to dispute, because they are facts. It draws difficult-to-argue conclusions, including that our near future is likely grim. That said, I think Schlichter’s elite/normal framework misses important nuances and is a bit too glib. But even so, the well-deserved spanking Schlichter gives the Left is worth the price of admission.

Militant Normals is an enjoyable read, a rollicking journey with the acid tongue of Kurt Schlichter as our tour leader. It is full of facts that are impossible to dispute, because they are facts. It draws difficult-to-argue conclusions, including that our near future is likely grim. That said, I think Schlichter’s elite/normal framework misses important nuances and is a bit too glib. But even so, the well-deserved spanking Schlichter gives the Left is worth the price of admission.

Schlichter, a combat veteran, former Army colonel, and now trial lawyer in Los Angeles (apparently being in enemy territory is in his blood), is a popular media personality. Part of that is his bewitching ability with the funny-yet-edged sound bite, visible on Twitter (on those rare instances I visit that cesspool) and in frequent television appearances. It’s also visible in his earlier books, all near-future histories, one of peaceful conservative dominance of the United States (Conservative Insurgency), and two of civil war between Left and Right (People’s Republic and Indian Country). The overriding theme of all his writing, even if he occasionally tries to gloss it over with optimism, is that the modern Left and Right are locked in an inescapable and existential conflict.

For years I resisted this idea. Sure, the Left in the rest of the world was responsible for the vast majority of unnatural human suffering and death for the past century. But in America, we had American exceptionalism, and part of that was a constitutional structure that permitted us to all get along. It turns out, though, we cannot all get along, and that’s because of the way the Left views the world—as a place that can be perfected, and where those who block that perfection must be made powerless or destroyed. Now it is clear to us all that there can be only one, that either the Left must rule or it must be destroyed, and the Left’s hobgoblin behavior in the Brett Kavanaugh farce this past week is only the most recent and glaring confirmation of this basic truth.

What Schlichter offers here is “a simple and coherent explanation for why American society has become so polarized over the last few decades.” On the surface, this is not necessarily about Left and Right. In short, he tells us America has long been divided into the Elites and the Normals. How did the Elites become the Elites? “The Normals ceded the Elite the authority to do certain work organizing and running society’s institutions with the understanding that the Elite could collect certain benefits (money and prestige) in return for competently executing these tasks for the benefit of Normals.” Thus, the Elites chose to be Elite; the Normals chose to live their lives without paying much attention to who was running the institutions. Now, for me, this is a little bit too pat and smacks of Lockean social contract fantasies. Aristocracies, which is what the Elites really are, are organic, not bargained exchanges. On the other hand, in the American context this comes fairly close to the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century truth. By itself, in any case, this structure actually makes a lot of sense. Everybody wins. But the polarization results because our modern Elites have corrupted it.

The most relevant “institution” here is the government, but there is an entire web of institutions that rule society, consisting of branching aspects of the media, entertainment, and academe. Collectively they have immense direct power, as well as the power to inflict social harm. Instead of accepting that the institutions are a trust, our modern Elites have greatly expanded the power of the institutions, for their own benefit, while at the same time removing any Normal influence over them. As A. J. P. Taylor said of England, “Until August 1914 a sensible, law-abiding Englishman could pass through life and hardly notice the existence of the state, beyond the post office and the policeman.” The same was true in America, but no longer. Moreover, in the past, the Elites shared many of the values of the rest of the country, and if they didn’t, they kept their thoughts to themselves. And they mostly did a reasonably competent job running institutions. Now, the Elites openly hate and despise the Normals, and run the institutions alternately incompetently and in an evil fashion (e.g., handing the bill for the 2008 financial crisis to the little people while bailing out the bigwigs; encouraging illegal immigration; and humiliating the rubes by demanding they let mentally ill “transgender” men use the bathroom with their little girls). That is, it’s not that Schlichter objects to the existence of elites. It’s that he objects to this set of elites. He is the first to admit that every society develops elites, and that, in fact, if the Normals disappeared, the Elites would then divide into the New Elites and those excluded from that group.

Schlichter notes that the Normals have occasionally risen up to express their displeasure and, this being a democracy, to impose their will by pushing back. Ronald Reagan’s election is a classic example; also intermittent tax revolts, and the Tea Party. Those eruptions dissipated, though, in part because Normals do not derive their meaning from political action. But now, Normals are coming to realize the existential nature of the fight forced upon them by the Elites, so they have become Militant Normals, who are not going back to their normal lives, because they realize they can’t. The most visible effect of this fire hardening is Trump, to whom the Normals turn, most of all, because he offers to fight for them and for what they hold dear.

You will note that so far, much of this discussion is not around the politics of the Elites, but their abilities and general relationship with the Normals. We know viscerally that our Elite acts Left, but there is no obvious reason that elites have to be Left. And, in fact, Schlichter says some of today’s Elites are conservative. By that he seems to mean two groups: individuals like me, who are Elite by background and career, but are not interested in being part of herd Elite behavior, and “Conservative, Inc.,” the emasculated traitors for whom Schlichter saves many of his most vicious attacks, exemplified by the unholy trinity of Bill Kristol, David Frum, and Jeb! Bush. (I didn’t know that in 2013, as head some fungible Elite institution called the National Constitutional Center, Jeb! gave Hillary Clinton a “Liberty Medal” for her dedication to the Constitution. Enough said.)

I suppose that’s true, but the reality is that today’s Elite in the sense Schlichter uses it is indistinguishable from the Left, in its Alinskyite/Bill Ayers/Pol Pot manifestation. In practice, Elite and Left are interchangeable. Yes, some Elites may be conservative, but when push comes to shove, they are not allowed any influence at all over what the Elite dictates, regardless of whether they want to exercise influence, which Schlichter would say is almost never. On the other hand, Normals are not conservative, necessarily, except inasmuch as having the freedom to not be crushed by government taxes and commands is inherently conservative. Many are apolitical; most could be most accurately characterized on the spectrum as center-right.

And the elephant in all this is Donald Trump. Schlichter admits that he started out, during the 2016 campaign, as very anti-Trump, often invited on CNN as a #NeverTrumper (until his apostasy, whereupon he was kicked off). This book is in some ways an explanation of how he came around. (I was always pro-Trump, vaguely at first and then emphatically, and predicted his victory, though his performance has far exceeded my actual expectations.) Schlichter makes a lot of good points about Trump, but he makes one of particular interest to me—that, although the Elites can’t see it because they viscerally hate the very idea of such a creature, Trump is, boiled down to his essence, an alpha male—a competitor and winner. “He was manly in a way few men in the public eye had been in a long time.” It is no surprise, given the Left’s demands for the forced feminization of society, that they hate Trump (though that is far from the only reason). Moreover, I think Schlichter is correct, that “He was best understood as a third-party candidate infiltrating the party apparatus and taking it over for his own purposes like some sort of political virus.” I don’t know if Trump is a genius, but I’m more willing to entertain that than I have been in the past, and his masterful handling of the Kavanaugh circus, which has been tremendously destructive for the Left, and more importantly, tremendously illuminating for the Right, suggests that he is.

The book does ramble and repeat. What I outline above is not particularly clearly laid out, but it’s there. Militant Normals is at its best in chapters that describe exemplars of the life and political development of a Normal (let’s call him “John,” though Schlichter says “you”), ending in why he votes for Trump, and of an Elite (nastily named “Kaden”), who begins and ends as a clueless social justice warrior. The characterizations are spot-on and hilarious. What is important to note, though, is that to any Normal, both types are clearly recognizable and, to a point, understandable. If you asked John to neutrally describe Kaden’s arc, he could do it pretty easily. But Kaden could not say anything except negative caricatures about John. This is an example of the bubble that all Elites live in—they can go through life with no exposure to Normal people or Normal ideas at all, while the same is not true for Normals. Irritating for Normals, to be sure, but it gives the Normals power relative to the Elites, since to defeat your enemy it helps to understand him.

OK, so that’s Schlichter’s framework. It is useful, but imperfect in a few ways. First, Schlichter’s definition of Normals is too simple and gives too much agency to Normals. He defines a Normal as “someone who does not choose to identify with the Elite.” The reality is that most of the time, the Normals are not given the choice to identify with the Elite, even aside from that aristocracy is largely an organic process. True, part of being Elite in America today is the aping of certain manners and beliefs. But part of it is passing through filtering mechanisms that are simply not available to most Americans. I, for example, went to a big midwestern university, but never once heard the term “investment bank” until I was in law school. The children of elites, on the other hand, are told throughout college about desirable jobs in investment banking or management consulting, jobs that act as feeders to other Elite activities. Such small examples could be multiplied until it becomes obvious that most Normals are born to their role; the rare exceptions, like J. D. Vance, prove the rule.

Second, Schlichter’s definition and analysis of the Elites is a bit too slick, because almost nobody is actually “elite,” in the traditional use of the term, in today’s American society. Schlichter’s use of the term “Elite” confuses matters; really, a better term would be something like “Dominants.” To the extent they are an aristocracy, they are a rotten aristocracy. A more precise way of looking at elites within a modern, democratic framework is José Ortega y Gasset’s, in his classic The Revolt of the Masses. For Ortega, the elite is those who demand excellence from themselves. (Note that this excellence is not the excellence of the technician, such that, say, top scientists are elites. Rather, it is broad excellence of mind and character, so almost all “experts” are not elite in any way.) In this framework, Schlichter’s Elite are not the Elite; they are “mass men,” mediocre and proud of their mediocrity. But the Normals are mass men too. In fact, nearly everyone is a mass man nowadays, which was the “barbarism” that Ortega predicted and feared. Real elites, those who demand of themselves excellence, are a lot rarer for us than they should be in a well-functioning society, and unlike in a normal, well-constructed society, those elites are not prominent and have no power. Who could be considered elite in this way today? Probably some private citizens of whom you and I have never heard, along with a few conservative academics. This is an underlying problem to what Schlichter describes, which is concealed by the obscuring double meaning of the term “elites.” I suppose, though, in a popular book, and given the contempt that conservatives have come to associate with the word “elites,” Schlichter’s choice makes sense.

How this will end is anyone’s guess. Schlichter clearly thinks, from what he says here and from his novels, that conservatives will win, because when roused, they have the weapons—that is, the weapons that go bang. I tend to agree, but rousing conservatives is a lot harder than it seems, and the Left offers seemingly sweet things, as Satan offered the apple to Eve. Plus, the division between virtue and vice is not only between Left and Right—certainly, all the Left offers is vice and evil, but all of America is shot through with decay, the inevitable fruit of the Enlightenment, and the Right is not at all immune to this rot. If the Left converted en masse to Schlichter’s way of thinking, which I call Agnostic Pragmatic Libertarianism, we would still face enormous problems and political divisions. But removing the Left from all power, permanently, is the place to start; we can argue about the best way to restore virtue and competently run the country thereafter. And, it is important to note, absence of the Left does not mean rule by the Right—it could just mean going back to an America just like the pre-1914 England of A. J. P. Taylor, where everyone gets to live his life as he chooses, within a weak framework that, hopefully, encourages virtue. Everyone but the Left can agree that would be a huge improvement.

Regardless of mechanism, I think the Left in America, and in the modern West, is doomed. It has merely taken longer to reach the breaking point than it took under Communism, but the principle is the same—political systems that deny reality are fatally compromised from inception. And the mechanism of their fall is always the same—their reach exceeds their grasp, and calls forth a reaction from the Normals, led by a real elite. The Normals are slow to come to this point, both by temperament and, where conservative, by principle, but eventually they will reach it. A cornered animal always fights. The best example of this is the beginning of the Spanish Civil War—Communism gained power through the usual mechanism of lying, but then, because they couldn’t help themselves, proceeded to slaughter their ideological enemies, to which Franco’s rebellion was a response. The exact same mechanism, minus the killing and the rebellion, has been on display the past two weeks in the Kavanaugh nomination. One of these days, probably soon, it will no longer be “minus.”