I suspect that very few people under forty know who Robert Gould Shaw was. Those older may remember the 1989 film Glory, which told his story. That movie could never be made today (and will probably soon be disappeared, as has been 1964’s Zulu). After all, Shaw’s is an out-and-out “white savior” story, and now that everyone has been educated that the African reality is actually Wakanda, we realize that black people don’t need, and have never needed, a man such as Shaw. Yet even though the Left has racialized all of American life and shrieks ever louder for a race war (something I failed to predict, silly me), I will only touch lightly on race in this review, and will focus on heroism, the traditional center of Shaw’s story. To race, we will return another day.

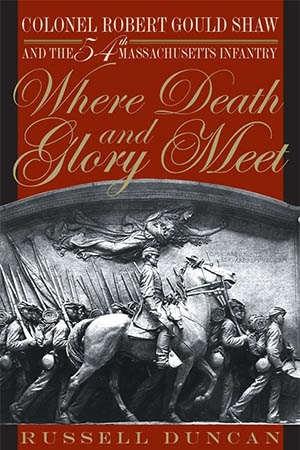

Where Death and Glory Meet is a short book, written in 1999, which is really just a very modest expansion of the long biographical preface written by the author, Russell Duncan, for his 1992 book compiling Shaw’s Civil War letters, Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune. If you’re interested in Shaw, just buy the latter book. Reading letters, from back when people wrote letters, is always an excellent way (especially if there are good editor’s notes, as there are in Blue-Eyed Child) to understand a person and a time. Shaw’s biography is short because his life was short—he died, cast into a mass grave with his men, at twenty-six, and his body lies there still, now beneath the waves off Charleston. But once he was among the most famous heroes in American history, whose name was known to every child, and whose deeds were taught as exemplars of virtue. This was entirely appropriate, as we will see, but is now sadly lost.

You Should Subscribe. It’s Free!

You can subscribe to writings published in The Worthy House. In these days of massive censorship, this is wise, even if you normally consume The Worthy House on some other platform.

If you subscribe will get a notification of all new writings by email. You will get no spam, of course. And we do not and will not solicit you; we neither need nor accept money.

Who is a hero? The word has been stripped of nearly all meaning, through promiscuous use to describe those unworthy of the term. It is now often attached to those whose actions have at best a modest heroic tinge, and even more often used to elevate, usually for ideological reasons, those who are not heroes at all. Such cheapening was no doubt inevitable; the nature of heroism, which by definition means that one person is lifted above the average, the mass, is that some receive recognition, honors, and prestige, based on their accomplishments, while others do not. This cannot be tolerated by the levelers who have wholly taken over American culture, and most importantly for these purposes, American education, for the past fifty years.

Why do the levelers see the old view of heroes as unjust? Part of it is no doubt envy—the types of people who push levelling are the types of people who lack the virtues and talents that tend to result in being heroic and receiving honors. Most levelers, after all, are parasites and malingerers. Part of it, closely related, is temporarily-ascendant Left ideology—forced egalitarianism is one of the two core doctrines of the Left (the other being total emancipation), and allowing one person to rise above others, and worse, to be perceived by all as doing so, cuts against this fundamental Left ideology. Rather than have no heroes at all, though, levelling is accomplished by pulling down, obscuring, and denying real heroes, and substituting people chosen from Left-preferred groups, even though they never accomplished any heroic action, and in fact usually deserve scorn.

But that still doesn’t answer who is a hero. A hero is someone who accomplishes notable deeds that benefit others, at significant risk or cost to himself, while exemplifying some key virtue or virtues. Thus, obviously, someone who wins a lottery is not a hero. He has accomplished nothing, taken no risk, shown no virtue. Less obviously, someone who, through hard work and talent, makes a major scientific advance is not necessarily a hero—it depends on the risk and the cost. Mere hard work is not enough. And as far as the benefit to others that is necessarily a part of heroism, it may be incidental, and not the intended main effect—the hero is often not a nice person. Achilles, for example, mostly sought personal glory, rather than the resulting benefit to his countrymen, yet his deeds were great, the risk and cost high, and his courage exemplary. Yet someone who imposes excessive costs on others even in the achievement of a noble goal is not a hero; the direct and foreseeable risks and costs must primarily be borne by the hero. (This is why terrorists, to the extent their actions harm innocents, can never be heroes, whatever their bravery and the justice of their cause).

You don’t have to fight to be a hero, or even struggle. Maximilian Kolbe was a hero, and he never lifted a finger against man or beast. But if you’re just doing your job, even if it’s risky, you’re not a hero. Not every soldier is a hero. Closer to home for most of us, and contrary to a claim often heard today, neither are most doctors. If, say, the Wuhan Plague had actually been notably dangerous to anybody other than a narrow group of easy-to-define people (the old; those with infirm lungs; the fat; male homosexuals), a doctor or nurse who attended plague patients would not have been a hero. If he failed to attend patients, he’d certainly be a coward, but bearing the risks attendant in your chosen line of work is merely what a society should expect, and what every person should expect of himself. It is not heroism. (Along similar lines, as with teachers, those who work in healthcare aren’t sacrificing at all by choosing that profession to begin with, and deserve no admiration for the mere fact of their choice.) To take the most prominent recent example, and leaving aside that Britain’s National Health Service is a disgrace on every level, the creepy recent requirement in Britain not only that people mouth praise for NHS workers as supposed heroes, but actually step out of their houses and show their literal obeisance to this crazy belief, as if they lived in North Korea, made a complete mockery of real heroism.

Sure, there can be a large gray area. A hero to one person or to one society is not always to another, and it’s often hard to recognize heroism in one’s enemies (the British, before they hit the skids, did it far better than the Americans do; witness Rudyard Kipling’s “The Ballad of East and West” compared to the Bush-ites who annoyingly and stupidly call jihadis “cowards”). Who is a hero is therefore in practice determined by an informal vote of the members of any given culture, if that culture is sound, and naturally someone acclaimed a hero in the moment may lose that status as emotions subside. Thus, to truly qualify for hero status, you probably have to keep it until most or all of those who originally acclaimed you a hero are dead.

All this matters because heroes, real heroes, are crucial to a society; they bind it together by providing object lessons and teaching everyone, in particular the young, for what to strive. They create true myth, and it is myths that make a society. Thus the erosion and cheapening of heroes in the modern West is yet another harm to our societies that must be reversed to move forward; studying Shaw is a reasonable place to start. We’ll get back to him, I promise.

What I discuss above are what might be called “public heroes.” But the same definition of hero can just as well fit “private heroes,” those without any spectacular achievement, or whose achievements may be completely overlooked, or even held in contempt until some later date (usually because of a change in perceived benefit to others, or in what is held to be virtue), when they may ultimately become public heroes. No surprise, public heroes are, in every society, always very heavily weighted toward men; it is in the nature of men to seek glory and resultant public honors, and that search frequently leads to heroic, often spectacular, action. Women simply lack that drive (and given the hyper-feminization of our society, this is another reason why real public heroes are denigrated, often replaced with risible female substitutes). But the woman who gives up all her free time to daily tend an aged relative in a nursing home is a hero in the strict definition, not only sacrificing but pushing back against the Zeitgeist, which holds that personal self-actualization and autonomy is the only rational way to live. She’s just a private hero; her actions will never have the impact of a public hero, but she should be honored nonetheless. Private heroes are no doubt more common, and although their deeds may only influence a family, or a small group, they still also serve a crucial role in binding a society together and in transmitting important lessons.

So where does Shaw fit into this? He didn’t start off as a hero, or seem to be a hero in waiting. That’s true for most heroes; who is a hero is usually partly the product of circumstance. Born in 1837, he was the scion of an extremely important and extremely rich Boston family, back when America had a decent ruling class. He had eighty-five first cousins, a sign of a confident, expanding society. His family was very antislavery—his parents, and their circle, were close friends, for example, with the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who was too radical for many in the North. We should remember that abolitionism was regarded as distasteful fanaticism by the majority in the North, especially by most of the ruling classes and nearly all of the moneyed interests, in the same way as, say, being pro-life is today viewed (and, after all, the evil of abortion is an exact philosophical analog for that of slavery, except that far more people have been killed by abortion). It was not the case, as sometimes put about later, that most in the North were abolitionists; far from it.

Despite his upbringing, Shaw himself was never an abolitionist, quite. He was an ardent American patriot (even though much of his schooling was conducted in Europe), and that tendency was what drove most of his thinking on slavery, which took second place to thoughts of girls and vague thoughts of doing something worthwhile with his life. Before the war, when he talked about slavery, his thoughts were that slavery was distasteful, disruptive, and reflected poorly on America on the international stage. But he didn’t agonize about whether the South left or stayed, as long as the annoying national tension subsided. During the war, he just wanted the conflict to come to an acceptable, honorable conclusion; ending slavery never became his main focus, although as with most Northerners, it assumed more importance in his thinking as the war ground on.

I say Shaw came from a decent ruling class, but the seeds of today’s ruling class perniciousness are evident in hindsight. His parents had substituted the social gospel for the real gospel, and though the objects of their attention were far more worthy than the objects of progressives today, emotivism as a driving characteristic of elite political focus was clearly aborning. His father was a dilettante, abandoning the mercantile pursuits of his forbears to read and scribble simplistic thoughts about capital and labor. He was a Unitarian, naturally (who, as it is said, believe in one God at most), and associated with men like Ralph Waldo Emerson, pushing the silliness of Transcendentalism, and women like Margaret Fuller, pushing the feminism that has ended in disaster for us today. In short, he was a tool. His mother was a strong but maudlin woman convinced of the total justice of her every goal, and she tried to maintain a tight grip on her son, hampered by his often being in Europe and liking to party.

As soon as the war began, Shaw volunteered. He had joined a unit of the New York National Guard beforehand, while national tensions mounted, back when the National Guard was actually a militia controlled by the states, rather than a mere extension of the federal government, as it sadly is now. But, again, ending slavery wasn’t his goal. Mostly, he wanted to prove his manhood by showing his courage, the usual reason men volunteer for the military, or did before economic benefits loomed larger and death loomed smaller.

He was, given his class and connections, quickly commissioned an officer, in the Second Massachusetts Infantry. Nobody ever said he was more than an adequately competent officer—he was brave, but somewhat inconsistent in his leadership, as often with introspective men, sometimes a martinet, sometimes a softie. He fought at Antietam, in late 1862. He was promoted to captain, but did not seek more promotions, content to remain with the Second. Thus he could have spent the whole war, had not circumstance intervened.

Black men were not initially enrolled in the Union army. Southerners nearly all thought the idea of black men fighting was both stupid and beneath contempt, but such sentiments were common enough in the North as well. Some prominent voices in the North, such as Frederick Douglass, who had Lincoln’s ear, nonetheless pushed to enlist blacks. Therefore, shortly after the Emancipation Proclamation, in January 1863, with the war going poorly and seeing a need for creative solutions to advance the Union cause, especially given the violent opposition to conscription, the Army began to enlist blacks, both free Northern blacks and freed Southern blacks.

The governor of Massachusetts, abolitionist John Andrew, had long been interested in raising black regiments. This goal had some unlikely supporters—the self-interested business class, whose heirs today can be found in the odious Chamber of Commerce. They were very rarely abolitionist, but they were keen to have as few of their factory workers, nearly all white, drafted as possible. (For this same reason, the business classes supported the Emancipation Proclamation.) As a result of this confluence of interests, Andrew decided, when authorized in early 1863 by the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, to raise regiments which “may include persons of African descent,” to form the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Infantry, an all-black regiment, of about a thousand men, commanded by white officers.

Among others, Shaw’s name was suggested as a possible commander. Andrew’s focus was not merely on creating additional fighting forces; he, and those around him, were keenly aware that the success or failure, real or perceived, of the Fifty-Fourth would have enormous impact on public views of the fitness and worth of black Americans to be full citizens of postwar America. Andrew approached Shaw through his father, knowing that Shaw was far from certain to jump at the chance, and that his father’s (and mother’s) opinions carried great weight with him. Even so, Shaw at first turned down the offer, to be promoted to colonel and lead the regiment. He was loyal to his existing regiment and his friends in it, living and (many) dead, and since he was never a particularly ambitious man, perhaps he was afraid of the responsibility inherent in the position and that some would think less of him for leading black men (he explicitly referred to not wanting to be the “Nigger Colonel”). Very soon he thought better of his refusal, and telegrammed an acceptance.

Black men flocked to the new regiment. Douglass recruited; his son Lewis signed up. Some of this was due to an aggressive advertising campaign by Andrew, and some black men, including some prominent ones, rejected the very idea of black men fighting before they had first been granted political equality (a logical position, but not a practical one). Still, the regiment was able to be very selective, choosing only healthy men deemed eager to fight. Training was rigorous; morale was high. Shaw, whose caring for blacks was abstract until this daily contact with his new black men, mostly ended his previous not-infrequent ridicule and disdain for blacks and stopped laughing at stereotypical black traits. He no longer called those of African descent “niggers.” And while running the new regiment, he got married, in May 1863, to Anna Haggerty, a social peer in the Boston elite, with whom he had continued to mingle while training his new men.

After three months of drill, however, it was time to, as the metaphor went back then, “see the elephant.” The vast majority of black men who volunteered for the 54th served with exemplary courage and competence. They knew the stakes, and they fought not only for the end of slavery, but to earn a maximized place for black people as American citizens in the postwar world. Men in that day, black and white, took the actions they took in open pursuit of virtues that today are denigrated, or taken as covers for “real motivations.” For the men of the Fifty-Fourth, those were duty, honor, and country (with women encouraging and coercing these motivations, in the usual partnership between men and women in well-run societies). All of this was acknowledged by the soldiers and the populace; as Duncan notes, when the Fifty-Fourth was sent off to war, the symbology was of “nation, state, manhood, home, Christianity, and higher law.”

A great deal rode on the Fifty-Fourth’s success—not just the political career of men such as Andrew, but the weight of the entire abolitionist argument, made by both black and white. Opposing abolition, and black rights, were not only Southerners, but many Northerners, including most notably Boston’s Irish, who as low men on Boston society’s totem pole disliked the idea of competing with black labor, or of black people crowding them on the totem pole at all. Success by the Fifty-Fourth could defeat this opposition. The Fifty-Fourth’s road was not expected to be easy; it was a long way from the universal high spirits that were widespread early in the war. Robert E. Lee had won a brilliant battle at Chancellorsville and was moving on to Gettysburg, though Ulysses Grant was rolling up the western edge of the Confederacy at Vicksburg. It was far from clear the Union would win, and if it did, it was obvious the cost was heavy and growing. And what the regiment did was under a microscope—the actions of the Fifty-Fourth were widely covered in the newspapers. Shaw’s parents even published some of his letters home, until he asked them to refrain from doing so.

The Fifty-Fourth sailed, or rather steamed, to Hilton Head, in South Carolina, and then went upriver to Beaufort (a beautiful place I went some years ago, much more peaceful now—whether it will stay that way, we will see). There he met with the Second South Carolina and the First South Carolina Volunteers, black regiments (also commanded by white officers) formed of escaped and freed slaves. James Montgomery commanded the Second South Carolina, and was the superior officer. Shaw and his men accompanied the Second South Carolina in a raid upriver on Darien, a Georgia seaport town, which they looted and burned, despite facing no resistance. Shaw was appalled. No doubt Shaw objected on principle, but just as, or more important, was that such an action reflected poorly on his soldiers, whom he had been careful to discipline and the propaganda impact of whose actions, for good or ill, he fully realized. Montgomery, a man with more than a little of the rigid Calvinism of John Brown in him, and who had fought with Brown in Kansas, offered the rationale was to bring home to Southerners “that this was real war.” Frederick Douglass agreed, as did Montgomery’s own commander; Shaw apologized to his men and told them they would have “better duty.”

And so they did. On June 25, 1863, they regrouped in Hilton Head, as part of the planned assault on Charleston. On July 8, after Shaw complained that his men were being used as laborers, not soldiers, they shipped to James Island, where the Fifty-Fourth competently repelled an unexpected Confederate attack, to Shaw’s delight and raising the reputation of the regiment. A major target of the Union assault on Charleston was Fort Wagner, which guarded artillery that itself guarded Charleston Harbor. At dusk on July 18, after an intensive artillery bombardment, the Fifty-Fourth led the charge against the fort. Shaw was given the option to decline, given that his men were “worn and weary,” but he knew the tremendous symbolism of black men being the key to victory, especially given the proximity of Fort Sumter. Shaw expected to die in the battle.

He led from the front; the bombardment had been ineffective. The regiment was torn by grapeshot and rifle bullets as it crossed the beach and climbed the parapets; Shaw was shot through the body at the top of a parapet. The Confederates repulsed the attack and buried Shaw with his men, but he had accomplished his purpose—to do his duty, not only to fight, but to show that black men could fight, and die, as well as any white man. The Fifty-Fourth fought on (Fort Wagner fell in September), and many other black regiments were raised, with the example of Shaw and his men inspiring others and dispelling skepticism and opposition.

Inevitably, his legend grew, fed both as deliberate wartime propaganda and by a groundswell of popular enthusiasm. Every tumultuous time and place has its human embodiments, and for a time Shaw embodied the North’s view of the war. It would be hard to deny Shaw’s heroism—he paid the ultimate price to benefit others, while showing unhesitating bravery and loyalty. Probably many in the South did deny it, but perhaps even they changed their minds as emotions cooled. Shaw’s reputation increased, perhaps peaking in 1897, at the installation on Boston Common of the famous Augustus Saint-Gaudens sculpture showing Shaw and his men, attended by the cream of American society and the survivors of the Fifty-Fourth. A few years back, I took my children to see it, and taught them of Shaw and what he meant, and of how they should, in their own lives and in their own way, follow his example. It is sad they are among the few who get such lessons.

Of course, the human embodiments of our time, at least those pushed by our ruling classes and their captive media, are cretins and fake heroes, and the poisonous vapors that emanate from them affect not only the living, but also the dead. So today the Saint-Gaudens sculpture is “problematic,” because it suggests that white people led black people to freedom. That’s undeniably the historical truth, the whole historical truth, but it’s unpleasant to today’s race grifters to admit it. No doubt the sculpture will soon be removed or destroyed, as with so many other monuments to past heroes. The good news is that we can bring them back after the next war, along with statues of new heroes that we will be sure to have.

You Should Subscribe. It’s Free!

You can subscribe to writings published in The Worthy House. In these days of massive censorship, this is wise, even if you normally consume The Worthy House on some other platform.

If you subscribe will get a notification of all new writings by email. You will get no spam, of course. And we do not and will not solicit you; we neither need nor accept money.