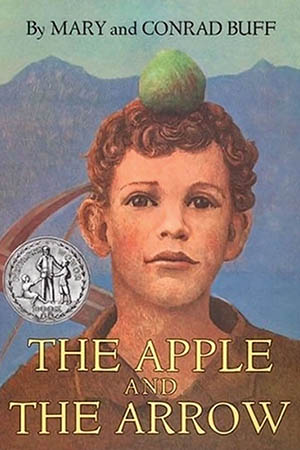

Do any American children learn about William Tell today? Do any Swiss children learn about him? Very few, if any, I suspect. My children do, but only because last year I was reminded of William Tell by Ernst Jünger’s The Forest Passage, and so I went and bought what few children’s books are still in print about the Swiss hero. Among those was The Apple and the Arrow, winner of the Newberry Medal in 1952, which I have just finished reading to my children, to their great delight.

Tell’s story is the core legend associated with the founding of the Old Swiss Confederacy, where around A.D. 1300 three communes (basically the cantons of today), Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden, agreed to act together for purposes of defense and trade. This was not the Common Market, a primarily economic arrangement. Rather, the Swiss expected to have to fight to maintain their political freedom, and they did. And like most legends remembered through the ages, especially those suppressed by our ruling classes today (which most are), the Tell story is chock full of useful lessons for modern men and women, some of which are thrown into highlight by today’s events.

The background history is a little complex, but in short at that time the ultimate overlord of all what is now Switzerland was the Holy Roman Emperor, though in practice day-to-day political control was usually in the hands of a greater or lesser ducal family. The Habsburgs, the villains of the Tell story, were originally just another such Swiss ducal family—“Habsburg” was not the family name, but the name of their castle in the Swiss canton of Aargau, which, like the three original cantons of the Confederacy, adjoined Lake Lucerne. Ducal rule was not the only arrangement—sometimes the relevant lord was a powerful local abbot (this was true for long periods in Schwyz) and sometimes a town or canton enjoyed “imperial immediacy,” direct rule (very light) by the Emperor, which in practice was, naturally, strongly resisted by the local dukes. For example, Emperor Frederick II granted Schwyz imperial immediacy in 1240, but the Habsburgs gradually accrued power there anyway—the Emperor was far away and had much else on his mind. By one method or another, by the end of the thirteenth century the Habsburgs exercised immediate control over all three cantons, but this was a control of short standing—not sanctioned by custom, the real source of most medieval law, and not liked by the Swiss, used to hands-off rule in their mountains and forests.

According to the Tell legend, Habsburg effrontery began the trouble. Rudolph of Habsburg died in 1290, and was succeeded by his son Albert, who decided to show the stiff-necked Swiss who was in charge. Albert sent a bailiff, or reeve, one Albrecht Gessler, to Altdorf, the main town of Uri, to administer the cantons claimed by the Habsburgs. Gessler set up a pole in the marketplace, atop which he placed his hat, and required all passers-by to bow to the hat. This was a double humiliation, and intended as such, for not only was obeisance to a hat not something free men were accustomed to, but Gessler himself was a commoner, and not even entitled to the modest deference the Swiss might have offered a noble.

The story from here is simple enough. William Tell was a huntsman of modest means living in Uri. He took his son to market, and Gessler’s soldiers demanded he bow to the hat. He refused, and was arrested and taken to Gessler. The reeve knew of Tell’s reputation for marksmanship, and so ordered that Tell shoot an apple off his son’s head, or they would both be killed. Tell, seeing no choice, took two crossbow bolts, put one in his belt and the other in his weapon, and successfully split the apple. Gessler, angry and no doubt suspecting the reason, demanded to know why Tell had put a second bolt in his belt. Tell refused to answer, other than saying it was a bowman’s custom, so Gessler assured Tell he would not be executed if he answered. Whereupon Tell told Gessler that if he had struck his son, he would have immediately taken the second bolt and killed Gessler.

No surprise, this enraged Gessler. But he did not break his promise—rather, he assured Tell he would die in prison. Gessler’s men took Tell in a boat, across Lake Lucerne, to the dungeon of Küssnacht. They never made it—a storm blew up, and Tell, experienced on the water, was untied and told to steer the craft. He brought it to land—and leaped off, fleeing into the forest, while the boat was carried by the waves back onto the lake. But Tell did not return home. Instead, he lay in wait for Gessler to either drown or to get to shore. He managed the latter, and with his men immediately proceeded to his castle—so Tell assassinated him from the shadows with his crossbow. This second half of the legend is often forgotten, when this tyrannicide is really the most important part of the legend—both the action itself, and that it began the forging of a new system, rather than being simply an attempt to turn back the clock, which is and can never be successful.

Thus began the Swiss war of rebellion against the Habsburgs, in which the key battles were Morgarten (1315) and Sempach (1386). In the latter, the Habsburg duke, Leopold III, was killed, allowing the Confederacy to expand. Today, with many twists and turns along the way, the Swiss still live under a political system with external characteristics not that different, most notably a subsidiarity extreme by modern standards, and the use of national referendums to decide important questions. The Swiss are, or were until recently, free—not a libertarian freedom that exalts individual choice, but an ordered freedom.

The Apple and the Arrow views the key events of the legend through the lens not only of Tell, but of his immediate family. The authors take some liberties with the traditional legend, most notably casting Tell as an active participant in a conspiracy against Austrian tyranny prior to running afoul of Gessler’s hat, whereas in the traditional version, he was an apolitical man radicalized by that event. No matter; the exact details of the revolt against the Habsburgs are long lost, and what matters is that the men of the three cantons agreed to fight, and did. They risked their lives, and won, for which their reward was to risk their lives again and again, since as the saying goes, freedom isn’t free.

That’s not to say the women didn’t matter—as always in the West, they mattered a great deal, they just didn’t pretend to be men, as women are told today they must. One key benefit of this book as a children’s book is that it depicts, and instructs children in, proper roles for men and women, those based on reality and resulting in a healthy society. The story offered is not the silly fantasy we would get if the book were written today, where Tell’s daughter would have the best crossbow skills in the canton, spend her days humiliating boys with her superior skills in every physical endeavor, and be solely responsible for killing Gessler, shrieking “Girl Power!”, while her father cowered in fear at home. In this book, rather, Tell’s wife, Hedwig, takes counsel with her husband, balances and smooths the edges off the defects that are inherent in masculinity (as he balances the defects that are inherent in femininity), and is an active participant, in a wholly realistic way, in the Swiss fight for independence, while never lifting a weapon or leaving her village. That’s the way a society should work, and mostly did work, until we were fed infinite amounts of lying propaganda about the past and sold a bill of goods about relationships between men and women, resulting in today’s pernicious chaos, pleasing and benefiting neither sex, that afflicts men and women today at all stages of their lives.

So I highly recommend this book. Even for adults, it’s a quick introduction to the Tell story, worth having in these days when it is mostly forgotten, or rather suppressed for the hero’s supposedly retrograde nature, for daring to accurately reflect reality and celebrate virtues that our masters deny are virtues. It’s a reminder of when awards such as the Newberry Medal, awarded by the American Library Association, went to worthy books. Today, the ALA is overtly racist and celebrates various perversions, and, inevitably, its awards don’t reflect merit, but its political priorities and its desire to indoctrinate children into its divisive ideology. You can be certain no book given a medal today focuses on, or even shows, a strong nuclear family, or shows men doing masculine things while women do feminine things. Now, the Newberry Medal’s primary benefit is to show a book to avoid. Schools, of course, eagerly use such guides, and similar collections that have gone full Left, such as Scholastic, to choose books to indoctrinate children. For example, my children’s school proudly displayed, before the Wuhan virus shut their doors, the covers of four books all grades under fifth must use to brainwash children. Two were racist and that was their main point. One celebrated homosexual penguins. To be fair, the fourth was mostly about kindness, although with racist overtones and encouraging an attitude of helplessness and handouts in tough economic straits. Needless to say, no book was written more than ten years ago, or was in any way a classic story, or will be remembered ten years from now.

It’s not just the Newberry Medal that has gone downhill. The Swiss have, too, though it took nearly seven hundred years. I’m not an expert on Swiss politics, but I think much of the recent turn to the Left winning national referendums is due to the dying out of the rural Swiss and their replacement with (also dying out, but more slowly) effete city dwellers who are mere carbon copies of the end-stage EU-loving drones of Germany. In recent years, for example, the Swiss have sharply limited the right to keep firearms (long correctly deemed necessary to maintain a free society) and imposed “hate speech” laws (always only ever used to suppress conservatives), among other stupidities. Today, Tell’s target wouldn’t be a foreign overlord, but the men of his own country who have stripped its people of their freedoms and bow to foreign ideological domination. True, in Switzerland as in other European countries, a party devoted to the country’s original ideals continues to gain power, violently attacked using the usual totalitarian tricks of the ruling class, and the outcome is ultimately in doubt (more so now with the Chinese virus spreading chaos in Europe, although the pansified global reaction to the pandemic gives more cause for pessimism than hope about the future).

I have talked elsewhere at length about rebellion and tyrannicide, so I will not specifically address the morality of Tell’s actions (short version: they’re awesome). Nor will I talk again about Ernst Jünger’s casting of Tell as the original “forest rebel,” which is a fascinating analysis very much worth reading. It interests me, too, but I will not talk today about, how the Tell legend illustrates the radicalization of men in the face of injustice—in essence, how and why men react to injustice by taking huge risks to inflict violence on their oppressors achieve a goal of which the risk-taker has no legitimate expectation of success and when he will almost certainly lose his own life. Not long ago, this was one of the most common storylines, across cultures—that men will often value justice far more than their own lives. But I will save that for another time.

Instead, let’s talk current events, that on which everyone is forced to focus. The Chinese virus has highlighted that in the West today the dominant ethos is that every person should value most of all his own life, at any cost that may be imposed on others or on broader society. This is fundamentally a form of cowardice, but less judgmentally (not that there’s anything at all wrong with judging others), it is a form of societal feminization, since protection is a core characteristic of women, in their nature. We see this in the global reaction to the Wuhan virus, which has sharply exposed many things, but in this context it has exposed how deep into the West the desperate desire for safety, at all costs but granted and directed by others stronger than ourselves, has choked us. Its manifestation in this moment is that rather than weighing risks and rewards, and choosing to bear burdens to accomplish goals, the vast majority of people accept, and even seek out, the most exaggerated worst-case scenarios as reality, and act on the basis of reducing risk as close to zero as possible. Everyone knows the internet has turned most of us into hypochondriacs, but maybe it’s not WebMD that has done that, but our own flaccidity and the simpering weakness of our “leaders.”

There is little doubt at this point that the death rate from the virus among the vast majority of people is very low. The obvious answer is to protect those actually at risk, or to let them protect themselves if they choose, and let everyone else get on with their lives, taking reasonable precautions. Yet there is no logical discussion, and any data that does not support the dominant narrative of overprotective panic is swiftly censored or memory-holed. Also pervading the hysteria is a strong element of wanting to avoid “stigma” by pretending that everyone is similarly situated; the desire to not stigmatize others or see them stigmatized is a feminine trait. And to the extent that activity, rather than passivity, is asked for by those in charge, it is second-order feminine actions, like initiatives for “kindness,” around which a municipality in my area has launched a massive campaign, complete with plenty of colored chalk drawings on local driveways. That’ll show the virus!

Everyone is told he must enter his government-provided mental cocoon and hold close his government-issued teddy bear, and wait for it all to be over. He complies, for he is no William Tell or forest rebel, even though there is no visible path for a return to normalcy other than by simply suffering for a short, sharp period, while doing our best to protect and aid those actually at significant risk. That truth is ignored and painted, for no specified reason, as evil. Instead, we accept and cower to the demands of legions of Karens, who lecture us that all that matters is following “the rules,” whatever those are today, whomever they are issued by, and whether or not they make any sense. And in truth, most of those ever-changing rules are the commands of the fearful women who run governments, either directly as political leaders, who may have been an adequate choice to coddle a weak but stable society, but were the wrong choice for a crisis, or who have foolishly been put in charge of our councils, rather than sent to nurse the sick.

Instead of acting with a forthright, decisive, manly, courageous attitude, the attitude with which our societies faced all previous pandemics and other civilizational challenges, we have knuckled under to hysteria, and collectively direct hatred at anyone who dares to question the approved narrative. This reaction is what’s going to be fatal, not the virus—though it more exposes the already fatal rot in the society than causes it, to be sure. The current sickness is just manifesting the core problem—a society that tilts its balance entirely to the feminine will always stagnate. Neither individual nor society can accomplish great things if the dominant ethos is protection of what one has and safety from danger in all events.

At least those forced to be at home can use the time to read this book, to themselves and their children. We could all use a hefty dose of William Tell, at every level and in every aspect of society. As this book narrates the thoughts of Tell’s son, finally understanding his father’s actions: “He knew what the wise had always known, that man lives by faith, and that faith can be stronger than fear.” Without faith in something broader, in our collective future and our resistance to tyranny, it doesn’t matter how many people die from the virus, for our society itself will die. But instead of calling for faith and decisive action, our leaders demand we cower in front of the television with no plan whatsoever, just a hope it will all go away and leave us alone. None of this will end well, and my bet is that the second half of the Tell legend will likely be generally applicable before long. Jünger predicted that “in the nature of things,” “when catastrophes announce themselves . . . the initiative will always pass into the hands of a select minority who prefer danger to servitude.” Let’s hope so.