The wicked reality of Communism has, over the past twenty-five years, been deliberately erased from Western education and, more broadly, from the Western mind. This was entirely predictable. The reasons behind the erasure are not complex. The ruling classes and social tastemakers in the West at the time that Communism fell, and for decades before and since, had and have a lot of sympathy for Communism. They were appalled by efforts, like Reagan’s, to actually end Communism, and they had no real problem with it in practice. To nobody’s surprise, today they have no interest in admitting their support for evil, or in exposing their guilt to a new generation. Moreover, as Ryszard Legutko has explained at length, Communism has much in common with modern liberal democracy—far more than liberal democracy has with pre-liberal forms of political thought. Education and the media are today controlled by these philo-Communists, throughout the West (with a few virtuous exceptions, notably Poland and Hungary). As a result, from a combination of self-interest and ideological sympathy and compatibility, the vast majority of people under forty today have little idea that Communism was the most evil and most lethal political system ever derived, because the truth has been deliberately hidden from them.

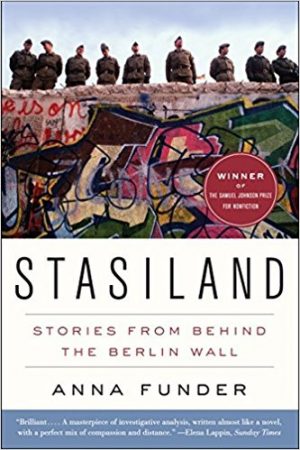

Anna Funder’s Stasiland, written in 2002 but covering the author’s journeys through the former East Germany in 1996 and 2000, is a partial corrective to this erasure of memory. The Stasi, of course, were the East German secret police. Stasiland is more of an introspective examination of individuals and their stories, heavy on emotions, including the author’s, than an abstract or statistical examination of tyranny. Certainly tyranny is very evident in this book, but it is not a history of the horror of Communism in East Germany, it is a history of a handful of people who lived through that horror. Perhaps, though, this is a more effective way of bringing home the reality of Communism. The Black Book of Communism documents precisely how Communism killed 100 million people, but the death of millions, as Joseph Stalin himself supposedly said, is a statistic, not a tragedy. Stasiland vividly shows us the inescapable and inevitable reality of Communism that is almost never taught and rarely talked about in America today.

You will have to read the book to learn the stories told by Funder’s interlocutors. It is impossible to do the stories justice, both factually and to convey their emotional impact, in a summary. Not all of her interlocutors are those who were persecuted. Some of them are Stasi agents and Stasi informers. Funder even talked to Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler, famous as the rage-filled talking head on GDR (“German Democratic Republic,” for those who have forgotten) television given the task of countering facts in broadcasts from the West. She quotes him at length justifying shooting anyone daring to try to escape from the GDR, as “humane” and necessary because “here in the GDR, peace has been elevated to a governing principle of the state.” That reasoning is pretty much par for the course for the former agents of the East German state that Funder interviews. But, aside from the stories themselves, several key points pop out to the reader.

One is that no Communists were ever punished in any meaningful way for their crimes. Funder chalks this up to a desire to forget on the part of the Germans. This is not correct, or rather it is incomplete. Doubtless some want to forget, but the Germans have not forgotten the National Socialists, because they have not allowed themselves to forget. The key principle at work, though, can be seen not in post-Nazi history, but in the more pedestrian history of the numerous leftist and rightist regimes that have ruled in various places over the past decades. When any right-wing authoritarian regime has ended in the past hundred years and been replaced with a more democratic regime, in which the Left is again allowed free reign, those in power under the prior regime, from the lowliest functionary to the maximum leader, are always persecuted around the globe until their death. This is done regardless of any formal legislation to the contrary, the rule of law, the doctrine forbidding ex post facto laws, or any other principle that might limit the revenge of the Left on their enemies, and it is conducted globally by the well-funded, well-connected, tightly allied Left, rabid dogs to a man. The best prominent recent example of this is Augusto Pinochet, and perhaps Alberto Fujimori. It is easy to adduce hundreds of examples, and when such men (often heroes, like Pinochet, who saved the lives of innumerable Chilean citizens) are not judicially persecuted, they are ostracized and humiliated, spat on and forbidden to travel. But not a single example can be adduced of the reverse process, of the persecution of leftists formerly in power, anywhere on the globe, at any time, even though leftists have killed far, far more people than rightist regimes. It is amazing, if you think about it. No Communist or leftist formerly in power in Central or South America, or Europe, or anywhere, has ever been punished with anything more than a slap on the wrist, no matter how many tens of thousands they killed. In most cases, like Fidel Castro, they have been globally lionized, free to travel in luxury anywhere, at any time, with no fear of criticism, much less punishment. While Funder does not draw this specific contrast between the treatment of Left and Right, she does cover how Erich Honecker, Erich Mielke, and other mass murderers, along with tens of thousands of other killers and torturers, received zero punishment. (Bizarrely, the only crime Mielke was convicted of was two murders of policemen committed in 1931.) In fact, all former Communists for the most part quickly became embedded in the new regimes, often personally greatly profiting, and not facing even social ostracism. Moreover, the higher-profile Communists were, after their fall, openly celebrated around the world by the Left. Their lives were mostly awesome, post-Communism. Nice work if you can get it, I suppose, but a few more such bad men floating face-down in canals, if the law will not do its job, would have been, and still is, a good idea.

A second key point is the total corrosion of civil society that was created by the informer state set up by the Stasi. “Relations between people were conditioned by the fact that one or the other of you could be one of them. Everyone suspected everyone else, and the mistrust this bred was the foundation of social existence.” This is not surprising, given that there was one informer in every seven citizens, and that the Left, unlike rightist authoritarian regimes, functions mostly on terror (rather than simple political repression), of which informants are a critical element. Funder gives an excellent flavor of this corrosive terror, which is also well shown in The Lives of Others, the 2006 film about life in the GDR (although that film was criticized by some, including Funder, for inaccurately portraying the GDR and the Stasi as softer and more humanized than they really were).

A third point is that Funder explains why anyone would join the Stasi, or become an informant, at all. To us, living in a mostly free society, it seems like an odd choice to voluntarily become an agent of terror. But, “In a society riven into ‘us’ and ‘them,’ an ambitious young person might well want to be one of the group in the know, one of the unmolested. If there was never going to be an end to your country, and you could never leave, why wouldn’t you opt for a peaceful life and a satisfying career?” This strikes me as a cogent analysis, especially in a society where Christian morality has been erased and all that is left is self-interest, with no responsibility to one’s fellow man. And it is closely related to C. S. Lewis’s concept of the “Inner Ring”—that people will often compromise themselves without limit merely to obtain a sense of being in the ruling group. In another passage in the book, Funder quotes a Stasi officer, asked “Why did [the informers] do it?,” as responding “Well, some of them were convinced of the [Communist] cause. But I think it was mainly because informers got the feeling that, doing it, they were somebody. . . . They felt they had it over other people.” This feeling of “having it over other people” is a key driver of the Left’s will to power, and a major reason why leftist regimes are able to maintain their power even when they are obvious criminal states not even bothering to pretend to adhere to their own ideological premises.

Most interesting, perhaps, is something not covered in the book at all, and that is the book’s reception in Germany. In 2016, in connection with the re-release of the book, Funder discussed at length that Germans received her book mostly with either active hostility, in the case of innumerable former Stasi agents or informers and their allies, or with icy silence, in the case of most other Germans. In the latter category fit both West Germans who, for the most part (as Funder also notes in the book itself) don’t like to talk about Communism, probably for the same reasons that the American ruling classes don’t like to talk about Communism, some combination of shame at their own actions and active sympathy for Communism, and East Germans who want to believe that the GDR was somehow not all that bad. Funder cited (in 2016) one of her interlocutors, “Miriam,” who now refused to give her real name publicly in connection with the book, because in her new job in public broadcasting her bosses were all former Stasi informers who loathed her for having been a political prisoner. “[Her bosses] disliked, too, that she sometimes objected to the news directors relegating an item showing the GDR or the Stasi in a bad light to the end of the bulletin, or not broadcasting such pieces at all. [Miriam] objected to what she saw as strenuous efforts, in the public broadcaster, to show the GDR as a harmless, safe welfare state with high ideals; she objected to the rampant Ostalgie [simpering nostalgia for the GDR], the Verharmlosung (rendering harmless), and the Schönreden (whitewashing). Miriam had spent almost her whole life battling the Stasi, and they were still there. She was tired, on a short-term contract and vulnerable. It would simply have made her working life too difficult to publicly ‘out’ herself. She decided not to come on television.”

Funder chalks this up, with an analogy to those who fought Nazism, to the need for some decades to pass for heroes who resisted tyranny to be rewarded. Sadly, this is not correct. She says it will probably take twenty or even twenty-five years. But that time has passed, and there is no such movement at all, as Funder’s 2016 discussions showed. I can confidently predict that in twenty years from now, or forty, or sixty, not only will there be no such recognition of heroism, but the heroes will be mostly forgotten, and when remembered, cast in a dubious light. They will be viewed as men and women of mixed character, who, because the evils of Communism have been mostly or totally forgotten and suppressed, will be criticized for extremism and failure to recognize the supposed good aspects of Communism, which resisters to Communism will be seen as having undercut by their opposition. Thus, they will receive no honor at all.

The naked truth is that the Left, which controls all of German social and political life today, likes and has always liked Communism, and hates and hated those who opposed it. Until their power is broken (which may, indeed, happen before twenty years are up, in which case I withdraw my prediction), there will be no recognition of the heroes who resisted at great personal cost. In Hungary and Poland, which have, fortunately, already partially broken the power of the Left, such recognition has occurred and is continuing, suggesting I am right, and Funder is wrong. In fairness, though, Funder does acknowledge the possibility of recognition never coming, though under a different mechanism: “There may never be [such recognition], if the Stasi win the PR war they have been waging, a war apparently supported by a general public that does not want to have to acknowledge this second lot of twentieth-century-German evildoers.” But it is not just the former Stasi—it is their allies and comrades in arms, the Left in general, both in Germany and globally. They are responsible for the evils of Communism, not, as they would have it, some unspecified, vague set of forgotten men and women, more sinned against than sinning, misled by their desire to achieve human happiness. All of them should be held to account, and punished accordingly.