To the extent you have heard of Warren Zevon, it is probably because David Letterman devoted an entire episode of Late Night to him when Zevon was dying, in 2002. That appearance shined up Zevon’s star, which had faded greatly since his glory days in the 1970s. It was not the mere fact of Zevon’s appearance, it was his sardonic humor about his own looming death from mesothelioma, combined with the fact that he was going down like a man, refusing any treatment and instead finishing his last album. Such bravery, a virtue of the old school, combined with VH1’s simultaneous soft-focus documentary on his life, gave Zevon an aura of virtue. This book seems to have been designed, with his consent, to mostly dispel that aura.

I’ve always liked Zevon. He probably counts as my favorite pop singer, and since I have zero appreciation for any classical music, I guess that makes him my favorite musical artist (although a few others might be it instead). But until I read this book and did some other research, I knew very little about him. (I also absolutely loathe his most famous song, “Werewolves of London.”) I don’t typically buy much music, but even in the 1990s I had bought several of his albums, to which I regularly listened. I used his 1996 double-album compilation, also titled “I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead,” as play-on-repeat music on transatlantic flights, when portable CD players were the height of technology. Apparently I was one of the very few people buying his music then, showing, once again, that I have long been out of tune with the Zeitgeist.

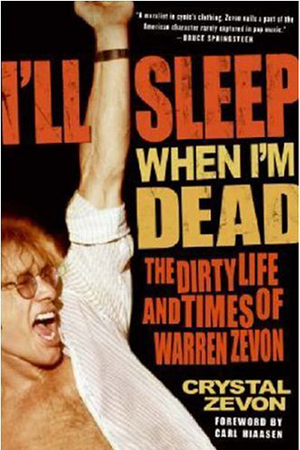

This book is an oral history, offering the voices of scores of people who knew and worked with Zevon, most of them his friends (and some of whom are famous, like Bruce Springsteen and Billy Bob Thornton). Combining these with journal entries from Zevon himself was done by Crystal Zevon, who was married to the singer from 1974 to 1979, but who remained intermittently close to him, and was the mother of one of his two children. He wanted a “warts and all” depiction, and he got it. Among many other vices, Zevon was a terrible father, a drunk who effectively abandoned his children when they were young, though in the manner of many such men, he developed a relationship with them when they were adults and he had sobered up.

It’s not that Zevon was a monster, just that he was enormously defective, defined in most things by a deep and desperate selfishness, exacerbated by living in a milieu where he never had to answer for his vices. He was pathologically afraid of responsibility and thus desperate to avoid having any more children; he ghosted long-term friends to avoid unpleasant confrontations; he dodged debts. And he totally lacked the discipline that characterized more successful rock singers, such as Springsteen, which is probably why after initial success and extensive critical acclaim, he never became rich or all that famous.

Such, perhaps, is a typical minor rock star’s life. Zevon certainly had an interesting family background. He was the son of a small-time Ukrainian Jewish gangster, part of Mickey Cohen’s Los Angeles mob. Born in 1947, trained in classical piano (he was a sometime acquaintance in his teens of Igor Stravinsky), by 1965, Zevon went to find his fortune as a musician. It took him nearly a decade of working for others, primarily the Everly Brothers, to hit the (modestly) big time. After a couple of well-received albums in the mid and late 1970s, from 1980 onwards his career was dim. He had been an extreme drunk for years, among other things often beating his (very many) women and waving guns around. That didn’t help his career either. By 1986 he sobered up, cold turkey, but his career did not revive, even though he kept releasing music, and for years often made rent by playing tiny provincial venues or corporate lobby gigs. His productivity was not helped by fairly extreme obsessive-compulsive disorder (one reason he bonded with Billy Bob Thornton), such as only wearing gray clothes (compulsively buying and wearing only gray Calvin Klein T-shirts), and, especially in his last days, mysteriously classifying everything, from days of the week to cans of Diet Coke, as lucky or unlucky. Only when he was dying did his music start selling again, an irony not lost on him, especially since many of his songs touched on death. His music, at least, only became lucky when he died.

What made Zevon different from most rock stars is that he seems to have been a genuinely extremely intelligent man. That comes through in his interviews and his journal (though there’s plenty banal in there too, even in the excerpts chosen for this book). His favorite activity when killing time before a show in a new town was to visit bookstores, and pictures of his apartment show it stuffed with books. And while he’s known for clever and acerbic lyrics, several of his songs show a quite deep history grasp, such as one from his 2000 album “Life’ll Kill Ya,” which, again ironically, was his last album before he got cancer. It has a song sung, in part, from the perspective of a knight of the First Crusade, which begins “We left Constantinople in a thousand ninety-nine / To restore the one True Cross was in this heart of mine.” The song itself is about pilgrimage, and the hope of the knight to return to Rhodes (true, the Hospitallers, associated with Rhodes and after Malta, were formed later, but maybe he was just a random knight who lived there). It’s a rare rock song that mentions the Crusades, much less casts them in a positive light. I’m betting this is the only one, and that says something about Zevon.

Still, he will never, in the foreseeable future, be lionized. In these days of #MeToo, a womanizing wife beater isn’t likely to join the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. He’s never even been nominated, though he’s been eligible for years. Reading some recent articles on him, the term “toxic masculinity” kept popping up (in the articles, not in my mind—I’d never use that term myself without vomiting). Moreover, and probably the reason Zevon was frowned on by the Hall of Fame prior to #MeToo, he was relentlessly unpolitical, refusing the attempts of close friends like Jackson Browne to involve him in whatever was the cause of the moment. His detached, jaundiced eye probably wouldn’t let him. When his daughter tried to interest him in her service of “underprivileged kids,” he dismissed it as “working with the little brown children.” He wasn’t racist; he just thought it was silly, or maybe he couldn’t bring himself to care about others. It’s hard to say; Zevon’s personality seems protean, or at least slippery. As one of his friends says in this book, “I’m not sure what the psychological classification of Warren would be. When someone who is an alcoholic plays at being a sociopath, it’s hard to know when playtime is over.”

I don’t think there are any large lessons to be drawn from Zevon’s life, other than the cliché that everyone acknowledges but rarely practices, to be kind since one never knows how hard the road is that another person is on. Yes, Zevon could have done himself and others a favor by striving harder to behave better, but who knows what demons drove him? And whatever his vices, he seems to never have been deliberately cruel, or consumed by those cold vices that C. S. Lewis identified as flowing from pride and as far worse than the sensual vices. Zevon was proud of his music and sensitive to criticism of it, real or imagined; he was not proud in the sense of lording it over others. Was he a good man? Not really. But at the very end, he played the hand he was dealt, without bitterness or complaint, praying only to make it to the birth of his first grandchildren, boy twins. Which request he was granted, so if that is a mark of divine favor, maybe beyond the very end luck finally stuck to him, and he has squeezed through the strait gate to enter the bright land from whence the shadows come.