I have always loathed the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen. Bleak, unhappy, and cold, they depressed me as a child, and I’m not a depressive person. True, that is painting with a broad brush, but you read “The Little Match Girl” and tell me I’m wrong. Even Andersen’s stories that are not overtly melancholy are full of the chill of the North; there is no brightness there. Much the same spirit permeates these short stories by Hannu Rajaniemi, a Finnish science fiction author. As with Anderson, the stories are clever and original, but they dampen, rather than uplift, the spirit of Man.

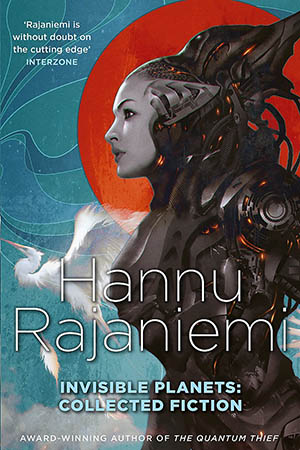

I heard of Rajaniemi when listening to a podcast of Palladium magazine, a very good new publication that focuses on the post-liberal future, though taking a different angle from me. He had excellent knowledge and analysis of classic science fiction, and he did not seem to be interested in being woke. His major works are a trilogy about a post-human solar system, beginning with The Quantum Thief. I did not want to commit to reading something long, so instead I chose this, a collection of Rajaniemi’s short stories, some of which revolve around the same themes as his longer fiction.

The first few stories are of a near future where some combination of artificial intelligence and accelerated technological development has created new fracture lines, between human and human and between human and machine. Now, I don’t think any of this is going to happen, but if you do think it’s going to happen, the stories are quite well done. Still, none of them embody what I call Heroic Realism in science fiction. They are a form of Perfectionism, seeing the perfect as the post-human, with the twist that they transport the gloomy emotion of “The Little Match Girl” to the near future, graced with quantum nanotech upgrades. Happiness is transient and ephemeral, if it exists at all. An icy cold, physical and emotional, surrounds each story. Presumably this is why the Finns drink.

Many of the other stories are not science fiction, but rather fantasy or horror, or some blend of all. Tuoni, the dark god of the Finnish underworld, shows up repeatedly. “I came upon a black river, deep and wide. On the opposite shore was a dark hill upon which stood a crooked house, larger on the inside than on the outside.” Death, death’s realm, and the gray zone between life and death recur over and over, including in the science fiction. After all, what are some post-humans but ambiguously alive? The reader is fascinated, but his hand creeps toward the bottle, or the gun.

While he is a very competent writer, I do not think it going too far to say that Rajaniemi’s fiction is more pernicious than the woke science fiction of the social justice warriors, which is laughable on its face and whose crude propaganda repels rather than attracts. Here, we are offered the bone-bleak vision of Hans Christian Anderson, updated and de-Christianized, yet offering the seductive vision of godlike power over nature, and not the knowledge of, but the superseding of, good and evil, gained through technological upgrades. It is not an accident, I think, that one story is titled “Deus Ex Homine” and another “Fisher of Men.” Much of this writing is a deliberate inversion of Christianity, a movement either backward to, or forward to, chthonic paganism, and a pulling down of man from, or a denial that he can achieve, truly bettering himself as man, in this life or the next.

Sure, none of the actual events in this book will ever happen, since artificial intelligence is a joke and we are very soon going to be moving backwards in scientific achievement. But the myths a society tells itself are critical for how it views itself, and how it acts. Rajaniemi’s myths are poisoned at their core; they will not serve to create the Instrumentality of Man, merely to help fracture what little coherent and lifegiving moral vision remains to the West. It is too bad that talent is devoted to such ends, but that it is, after all, is a sign of the times.