Symbology is a key element of any successful modern political movement. Animals are rarely modern political symbols; certainly modern mass ideologies, from Communism to National Socialism, have eschewed such symbology. Living creatures, whose exalted metaphorical political use was once widespread, are now usually mere lowbrow holdovers from the more distant past—elephants and donkeys, for example. Yet America, when it was America, used the majestic bald eagle with great success, and I think that when we seize the future, we need outstanding symbology. In this light, I am working on the symbology of Foundationalism, and this interesting book helped me focus my thoughts.

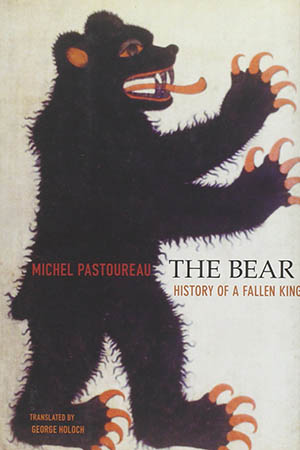

The Bear caught my eye because of a review in the magazine The American Sun (which also touched on symbology for the modern Right). The book promised to combine history and zoology in a package that I could put to my own purposes. The author, Michel Pastoureau, is a French medievalist known for his histories of colors (after learning that, I bought his book A History of Yellow, for my daughter, who has a strong artistic streak and whose favorite color is yellow). This book was originally written in French for a European audience; it therefore focuses on European brown bears. It says little about polar bears, and almost nothing about North American bears (the black bear and the American brown bear, the grizzly). Pastoureau’s basic claim is that in Europe, for millennia, the bear was the king of the beasts, and that it was consciously and methodically dethroned by the Roman Catholic Church. He has a tendency to make claims that exceed the evidence, but this core claim seems generally sound.

You Should Subscribe. It’s Free!

You can subscribe to writings published in The Worthy House. In these days of massive censorship, this is wise, even if you normally consume The Worthy House on some other platform.

If you subscribe will get a notification of all new writings by email. You will get no spam, of course. And we do not and will not solicit you; we neither need nor accept money.

Pastoureau begins with prehistory. In ancient Europe the bear was, it appears from archaeological evidence, the object of some degree of cult activity. In the Paleolithic, humans interacted mostly with the now-extinct cave bear, nearly twice as large as the brown bear. Such interaction was often in actual caves, occupied sometimes by man, sometimes by beast. Collections of bear bones arranged by man have been found in such caves, and bears feature in a variety of cave paintings. To what extent there were cults of the bear, such that the bear was a special animal to men, perhaps occupying some liminal space, or instead just an animal like any other, appears to be the subject of violent disputes among archaeologists. Pastoureau, perhaps unsurprisingly, takes the view that cults were widespread, noting a few specific examples, such as a Neanderthal and a brown bear buried in a common grave—although this interpretation of the gravesite is also disputed, since it may just show a bear ate a man and then died, mixing the bones.

When we enter history, we see that the Greeks embedded bears into myth. The goddess Artemis had the bear as one of her emblems, and Paris, seducer of Helen and cause of the Trojan War, was raised by a she-bear. This latter introduces what Pastoureau examines from various angles as an underlying thread of bear stories in Western culture—the interaction of humans with bears where the bear acts in a human manner, whether to raise a child or as a sexual ravisher, and often captor, of women. Around the time of Christ, however, the bear in part lost its mystery and grandeur in the classical world, due to Pliny the Elder’s disparaging of it, in his hugely influential Natural History, as stupid and mischievous.

As the classical world turned Christian, Augustine, following Pliny, also denigrated the bear, which supposedly conditioned Western Christian attitudes toward bears. But here the reader sees Pastoureau’s tendency to overreach from the evidence. He tells us Augustine disliked all animals, assuming with armchair psychoanalysis that this resulted “from some [unknown] episode in his childhood or youth.” He claims Augustine’s supposed zoophobia was very influential on medieval theologians, without much in the way of examples. Augustine did say “the bear is the Devil,” a phrase Pastoureau uses as the epigraph for the entire book. The context for this statement is not given, however, and although Pastoureau cites to where Augustine said this, in the footnote the phrase is actually “The bear prefigures the Devil; the bear is the Devil.” This suggests a more complex analysis. The citation is to one of Augustine’s many sermons, but I cannot find the whole sermon anywhere online to determine what Augustine’s larger point was. The only internet references to the phrase in English refer to this book—which doesn’t mean Pastoureau made it up, but it does suggest that he’s exaggerating the importance of the phrase. My guess is that Augustine was drawing some kind of Scriptural analogy to the natural world, something very common in his sermons, not making an existential judgment on the bear itself, as Pastoureau would have it.

Regardless, when Christianity came to Europe, it faced a bear problem. In Europe the bear was, from time immemorial, regarded as the king of the beasts. This was a natural choice, because the bear was the strongest European animal, unconquerable by any other beast. Other societies chose the elephant, the jaguar, the eagle, or the lion. The bear became a totemic animal, combat with which burnished reputations, whether of a young Scandinavian man entering adulthood or of an older man seeking more luster. Thus, Godfrey of Bouillon, before he became ruler of Jerusalem, was said to have defeated a giant bear in single combat, echoing the defeat by the shepherd David of a bear and a lion (found in I Samuel). But as a totem, the bear was seen (accurately) as a distraction from the true God at best, and an active rival at worst.

Pastoureau goes on a very long tour of European medieval history as it relates to the bear, tracing its long decline and fall from its perch as European king of the beasts. Charlemagne, eager to stamp out paganism and to increase safety, organized massive bear hunts (when he wasn’t hunting Saxons). Yet at this point, bears weren’t regarded as wholly bad; their old reputation stayed largely intact, and Pastoureau claims (on thin evidence) that bear cults continued in many areas. The Church, in the usual way, replaced pagan holidays associated with bears with new saints’ days, notably the feast of Saint Martin of Tours, even if more than one saint was portrayed as having a bear companion who served and protected him. And we follow a lengthy, winding path, in which the bear was gradually degraded in favor of the lion, and ultimately became an object of scorn and fun, seen most often as trained circus or dancing bears, and ridiculed in literature, while the lion became the king of the beasts in Europe (and the stag the object of prestige hunting). The bear maintained status in a few pockets of Europe, and was a sometimes-used heraldic symbol, but that was it for the bear, though it took hundreds of years.

There’s a lot of erudition here, but again, Pastoureau seems to stretch frequently and to make statements with more confidence than warranted. He also makes some simply false statements. He admits that the Arthurian legend says nothing about bears, yet tries to turn Arthur into a “bear king” based on some obscure phonetic comparisons and “atmosphere.” He states flatly that the name Beowulf means “enemy of the bees” and implies Beowulf is “the son of a bear and a woman,” something not at all agreed upon by scholars. And he incorrectly claims the medieval Church banned human dissection, a long-disproven myth. This is mixed with lots of interesting tidbits, such as medieval discussions about whether male bears could father human children (the origin of several Scandinavian family legends of being founded by a bear), so it’s not all bad, but I think you have to take Pastoureau’s broader conclusions with a grain of salt.

To take another example, Pastoureau claims that medieval theologians pondered the role of animals in creation, whether they had souls and might be redeemed. The supposed key Scriptural passage for this debate is Romans 8:21, which he quotes as “The creature itself also shall be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God.” Now, I’m perfectly willing to believe that some animals get to heaven, and some theologians hold that. (To me, it seems to go along with the resurrection of the body.) But that verse seemed odd to me, for the use to which Pastoureau was putting it. So, looking it up, it turns out that in English translations, only the King James uses the word “creature”; all others use “creation,” the standard translation of the original Greek word. It’s quite obvious that the King James is using “creature” not in the sense of “animal,” but of “all created things,” which removes the instinctive turn of the mind to “animal” when the modern reader hears “creature.” Thus, this verse proves far less than the author would have us believe. (How this was treated in the original French in which this book was written, I do not know.)

Somewhat to my frustration, after his initial talk about Greece, Pastoureau drops talking about any place but Europe. I am curious what the view of the bear was in, for example, the Eastern Roman Empire, or for that matter Persia or China, but we are not told, and maybe Pastoureau just doesn’t know. And then Pastoureau ends the book on a down note, straining to be topical and politically correct, incorrectly claiming that bears of all types, “black, brown, and white” are about to disappear, which again introduces false notes into his work.

So the book is fine, and interesting, despite its limitations. Let’s turn to my derivative topic, political symbolism. What of the modern symbology of the bear? You don’t find much about this in the book. Pastoureau makes a comment in passing, “the bear is sometimes recruited in the service of regionalist causes foreign to me.” He does not specify what those causes are, and his comment struck me as strange, because I’m not aware, and could not find any reference, to any causes that use bear symbology. (“Foreign to me” seems to mean not “unknown to me,” but rather causes with which he disagrees.) I don’t think he means Russia; the bear is a relatively recent symbol for Russia, and more importantly, one used by outsiders, not by the Russians. Regardless, there are a few, but only a few, other uses of bears nowadays. The California flag, for example, has a grizzly bear, although nobody pays much attention to that. Arktos Media, the right-wing press, is named after the Greek word for bear (something I did not know until I read this book, and the name is not explained on their site). But in general, the bear is simply not in use as a political symbol in the modern world.

Whatever current use may be made of bears, symbology is crucially important for a political movement. It allows easy identification of friend and enemy, and serves as a rallying point, physical and psychological. It permits the leaders to harness the energies of the crowd. Men will die for a symbol, where they will not die for an idea not reified by a symbol. Without some symbology, a political movement in the modern world might as well not exist.

Political symbols fall, I think, into three basic categories. First, metaphorical or translated symbols taken from the natural world, such as animals, which have fallen into desuetude as political symbols, for the most part. Second, human beings—traditionally monarchs of their country served as symbols, though little is left of that (I suppose the Pope might be considered a symbol of the Roman Catholic Church), so this is of no real relevance today, except in occasional cults of personality. And third, graphic images of no independent meaning (what would be called fanciful or arbitrary under trademark law). This last is the most common modern political symbology.

Both the Left and the Right have used graphic symbols in the modern era, say from 1900 onwards. The Left has, for example, created and used powerful symbols such as the Communist hammer-and-sickle and red star, or Sergei Chakhotin’s Anti-Fascist Circle. This latter has been repurposed by Antifa, and is therefore widely seen today (though not often understood by normies). The Right once also used such symbols with great success—most obviously, the swastika, but also lesser-known symbols such as the Hungarian arrow cross. At one point, symbols were, we all know, a key part of the battles between Right and Left—more so in Europe than America, however. In America, only the Left used symbology—not only the classic Left symbols just mentioned, but also other symbology, sometimes including animal symbols, such as the stylized eagle of the National Recovery Administration. That only the American Left has ever used symbology is not surprising, given that there was never any actual American Right until very recently, merely those opposed to a greater or lesser degree to the speed in which America was moving in a leftward direction.

This pattern continues today. In 2021, despite the rising-yet-inchoate Right, only the Left uses symbology to any significant degree, and thus there is no battle of the symbols. This is a major disadvantage for the Right, who can be cast as, and made to feel, isolated as a result. Yes, some fringe groups on the Right use symbology—the “Three Percenter” image, for example. One also sees not infrequent use of the Gadsden flag, but that merely proves my point, because that flag does not have any very clear meaning—it means different things to different people, and is not associated with any organized movement, or even a clear political set of values, which dilutes the benefit of the symbol. (You see the same thing with the use of the Confederate battle flag, which has lost its irredentist meaning and now is basically the same thing as giving the middle finger to our Left overlords, but despite the hysteria surrounding it in the media, is actually seen very rarely on the Right.) Still, the terror campaign of our current regime against those who use any such symbols, most aggressively against the Three Percenters, who set themselves overtly against our temporary overlords, suggests their fear at the power of symbols.

On the Left, the rainbow flag, the so-called pride flag, the symbol of ascendant globohomo, has recently been adopted in practice as the official flag of America. Notably, and with new meaning now, the American embassy in Kabul this past June made a big production out of their elevation of the globohomo flag above the embassy. Strangely to many, the Afghans didn’t seem to find it inspiring. (My guess, not an original one, is that action served as a powerful recruiting device for the Taliban, along with the other innumerable manifestations of globohomo pressed on the Afghans over the past twenty years.) True, today’s stupid and fractious Left can’t even settle on one version of the globohomo flag. They keep adding new stripes and colors to satisfy the latest and loudest set of freaky deviants. Nonetheless, flying the flag of globohomo means something very clear to the followers of that ideology (and, annoying me no end, has ruined the use of the rainbow for other purposes, yet another crime in an endless list of crimes that will need to be punished). Flying it therefore allows one to feel part of a larger group, to know one has allies and who they are, and who is the enemy, as well as to signify one’s supposed moral superiority. It is, as Wolfgang Schivelbusch said, the “symbolism of compliance.” The Right has no symbols like this.

This success suggests the Right, by which I mean primarily the American Right, needs to find a coherent overarching symbology. One obvious candidate is just the old American flag, the stars and stripes. The Left now treats this as a right-wing symbol, and so in practice simply flying it is now a right-wing statement. My problem with this is that it’s passive and doesn’t accept reality. America no longer exists, and while I’m fine with flying its flag, doing so as a political statement is basically a rearguard action, pathetically begging our enemies to not destroy our country, a task they’ve already accomplished, and are now moving on to planning camps for us. It does not call to battle and it does not embody any actual program. We need bolder action.

So, focusing on my own program, what should be the symbology of Foundationalism? We need an instantly-recognizable image, that can be tied to the political system, and does not carry, today at least, any particular meaning. I considered bears, after reading this book. But I don’t think that’s the right choice. Pastoureau is not wrong that the bear is no longer the king of the beasts. Perhaps the grizzly bear is, in America, but he conveys brute menace to humans, not majesty, and at the same time is sometimes seen begging handouts from tourists, neither of which conveys the desired flavor. Nor do I think animals in general are the way to go. Animals are associated with heraldry and thus the past; Foundationalism is not restoration, but a new thing for a new time.

We need an image that is a clarion call to action. The symbol must be clear and forceful, therefore memorable; the meaning attached to that identity will be filled in over time, but the identity must attract the viewer. We want someone viewing the symbol for the first time to say “I should learn more!” And we want the person who already knows the meaning to feel a swell of pride, recognition, and kinship; somewhat similar to how those of an a generally anti-government bent view the Guy Fawkes masks associated with “Anonymous” movements, but with a more positive and less alienated tone. Ultimately, of course, the symbol of Foundationalism will be a universally-known emblem of power, that people see and know, and some tremble. But that is a ways down the road.

Our symbology cannot seem backward-looking or stuffy. Foundationalism offers a new America, for a new age, informed by the wisdom of the old—the future Renaissance, not a throwback to the original one. The symbol should therefore look forward and upward. The goal of Foundationalism is returning to societal success and glory, not steeping in nostalgia. Since the quest for Space is a key pillar of Foundationalism, the symbol should embody some element of Space. There should also be a clear, but not excessive, masculine feel to the symbol—not because Foundationalism is exclusively for men, though certainly in a society based on sex-role realism men will do most of the ruling, but because hyper-feminization is one of the worst corrosions of the modern world, and a stance against it should be obvious from the symbology.

So I will, I think, hire someone to come up with this symbology. In modern times, the Left has tended to have better graphic artist talent. This is a historical anomaly, however—as I have demonstrated elsewhere, it’s just a myth that artists tend to skew Left. In fact, it seems to me that Left artistic energy is exhausted, in part in a pathetic striving to be inclusive (what has caused the silly mutations in the globohomo flag). The inability to be bold leads to enervation, and there is quite a bit of artistic energy on the Right. It’s found mostly in memes, and is disorganized, but can be directed and channeled. It’s also, unlike the Left, not heavily funded—but perhaps that’s an advantage, since art of this type is cheap to produce, and thanks to technology and despite massive censorship, easy to disseminate. Just wait a few months, and I will reveal the results!

You Should Subscribe. It’s Free!

You can subscribe to writings published in The Worthy House. In these days of massive censorship, this is wise, even if you normally consume The Worthy House on some other platform.

If you subscribe will get a notification of all new writings by email. You will get no spam, of course. And we do not and will not solicit you; we neither need nor accept money.