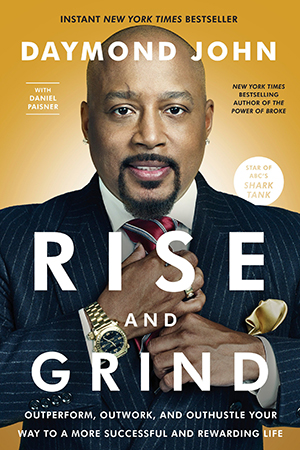

People often ask me, as I stride the halls of power in my custom Zegna suits wove with thread of gold, how I became so rich and successful. Like David Byrne, I too ask myself, how did I get here, with my beautiful house, and my beautiful wife, and large automobile? Such thoughts bounce around my mind, but they have crystallized after reading Daymond John’s Rise and Grind. I picked this book because John is my favorite regular on Shark Tank, a show I watch intermittently, and I was bored in the airport, looking for something to read. I’m not sure I learned anything new, but I was inspired to regularize some of my thinking about my favorite topic, myself, and now I will share it with the world.

I am not a frequent consumer of this genre that might be called “business self-help”—books that revolve around business, but shade, to a greater or lesser degree, into advice for people in their daily lives. On those few occasions I read such books, usually I either hate them, or can only remember a few points, since much of what most of these books have to say is unmemorable. Thus, I loathed Charles Koch’s Good Profit, and after I read Og Mandino’s The Greatest Salesman in the World, the only one of the ten didactic lessons I could remember was, no surprise to those who know me, “Today I will multiply my value a hundredfold.”

That lust for gold is inborn. When I was four or five, I can distinctly remember having two goals, both of which I assumed I would certainly achieve. The first was to be Pope. Although this seems like a religious goal, in fact it reflects poorly on me, because my aim was not spiritual leadership, but power. In my nature I wanted to be the most powerful person of whom I was aware—and that was the Pope. If Napoleon had been alive when I was a child, I would probably have wanted to be him. (Jimmy Carter was alive, and in power, but he was not the man to inspire a budding megalomaniac.) My second goal, the one we are discussing today, was to be rich. Since my family was very not rich, the only route I ever considered was earning money through business. And I have achieved my goal, by any reasonable measure.

Well, actually, I considered one alternate path. When I told my mother my plan was to marry a rich woman, she replied that was fine, but I should remember, that a man who marries a rich woman is not a rich man, he is merely the husband of a rich woman. (I am not sure if that is original with my mother. It sounds like Oscar Wilde, but I have not run across the phrase anywhere else, and the internet does not come up with it, in a quick search.) Still, I once asked the clerk at Tiffany if she knew any heiresses (before Tiffany started focusing on selling to the great unwashed). She demurred, probably thinking I was a creep, so I gave up. Thus, business it had to be, or nothing, after first spending some years as a lawyer.

What does any of this have to do with Rise and Grind? Quite a bit, actually. The book has one basic point, and it is same one that I have often made myself about what is necessary, before and above all else, to succeed in business. Listen closely. To be a winner, you must do two things, which, as of five seconds ago, I call the Golden Dyad. You have to work hard, and you have to get done everything that has to be done. I can hear you choke with rage, and say that is obvious, and I am wasting your time. Ah, but I will tell you why you are wrong.

The empirical reality is that at least ninety-five percent of people can’t do both of those things, and usually can’t even do one. This is partially because many people are lazy, but much more so because working hard is not just doing hard work. Rather, it consists of two elements. One is obvious. That is aggregate time spent actually working, and no, there are no shortcuts. But the second element is not obvious; it is what I call the “racetrack,” what John calls “the ideas running through your head.” Those are all the innumerable thoughts that are relevant to success in business, from to-do items to customers to bills to bookkeeping to taking the trash out to strategy, chasing each other around in a circle in your head, twenty-four hours a day. Your business must consume your mind, morning, noon, and night, and no, you cannot break this up or delegate it. Most people simply cannot do this. They lack the ability, or the will, to so focus. Actually it’s more than willed focus; it’s focusing so hard that it becomes the backdrop of existence, like breathing, not a matter of choice. Most people have to, or want to, spend time thinking about other things, like what’s for dinner or what’s on Netflix. Not someone who wants to be a successful entrepreneur.

This can be hard on others. If you’re married and don’t have spousal buy-in and support, it will probably be disastrous. My wife, who married me knowing that my grand desire was to, in her words, “build castles in the sky,” says that for the first few years after our marriage, when she saw me staring off into the distance, clearly somewhere else, she worried I was thinking about other women. Soon enough (though she helped in the business) she realized that I was, instead and always, thinking about money—by which she meant the racetrack, not cash itself. Dreaming about cash as cash doesn’t get you cash. But cash, the finish line of the racetrack, is independence, safety, and power, of which more later; accept no substitutes.

As to the second element of the Golden Dyad, getting everything done, it is a basic truth, which I cannot explain, that most people simply cannot do everything that needs to be done, immediately, without delay. As John says of himself, “I identify what needs doing, then I just get to it.” This is a function both of competence and decisiveness (it is always better to make any decision than to defer the decision; you can fix things later, on the fly, if necessary). But the vast majority of people list ten things, and do seven. Why? I have no idea. Maybe they’re afraid, or incompetent, or lazy. Beats me. Nonetheless, it is a truth universally acknowledged, or should be.

And what binds together the people John profiles in his book, more than anything else, is that they get things done. They also work hard, obsessively hard, in both senses of working. John chastises self-help gurus (read: Oprah) who say that visualizing success is the key. False: that only succeeds “if you’re willing to put in the work.” Truer words were never spoken.

The Golden Dyad is also an utter rejection of that stupid phrase, work-life balance. John quotes Nely Galán (a television executive of whom, like twelve of the fifteen famous people profiled in this book, I have never heard, which should probably tell me something). “When young people say to me, ‘Oh my God, I’m dying, trying to hold down three jobs,’ I don’t feel sorry for them. When you’re young, there is no balance, and there shouldn’t be balance. There’s plenty of time later in life for balance.” This is the also the truth. When I started as an entrepreneur, fourteen years ago, with no savings, one child, and a pregnant wife not working outside the home, I worked a second full-time job, with flexible hours, and ran various hustles to pay the bills. Similarly, John worked at Red Lobster for years after starting FUBU, as well as other side jobs, hustles, and deals, some of which worked out, some of which did not.

My own side deals and hustles were legal, certainly. But borderline ethical. For example, for six months I ran a bookcase-making business, before I started my current business. I had pretty good traffic to my website, as a result of teaching myself search engine optimization, back when it was still the Wild West and amateurs could do that. Even after I stopped making bookcases, having started my current business, I kept the website up, and redesigned it make potential customers go around in a fruitless, endless loop, searching for how to buy bookcases from me. Then I put Google ads on the site, so the most obvious way to exit, for someone looking for bookcases, was to click on the ads, for bookcases. I then drove even more traffic to the site by other dubious actions, like spamming Craigslist. I made $50,000, and that money fed my family. Clever me.

That wasn’t the only ethical line I sliced thin. When I started my current business (basically packaging liquids), I had no customers. I got one customer to sign on—contingent on my showing, within a certain time frame, that I could do the work. I ran out of time, able to complete “pilot” batches of only half the required products. I struggled with the others; I wasn’t sure I could do them. But rather than admit defeat, I went to retail stores, bought the customer’s current offerings, opened the packages, repackaged them, and sent them to the customer as my own work. (I called these “special batches.”) I kept the contract. (The irony is that the customer’s only comments about needed improvements were from the special batches, not the ones I had actually done.) Would I do it again? You bet.

Or, to take another example, I wanted, or rather desperately needed, to find more customers. Databases of thousands of potential customers, with decisionmaker names and titles, were available, organized by Standard Industrial Classification code. But they were very expensive, and I had no money. So I tried various logins, finally finding that “student” and “test” worked as login and password—and downloaded all I wanted for free (using a VPN to hide my IP address, just in case). Those databases, used to send letters to potential customers, got me my first big customer, which made the company. Stealing? Maybe, though is it stealing to obtain a good that can be duplicated at no marginal cost to the owner, if I never would have been able to afford buying it?

All this is merely living the Golden Dyad. But you can’t make a book out of the Golden Dyad, so John dilutes the message with checklists about other matters derived from his own experience and that of the people he profiles. Some of that advice is pretty good, but it’s all secondary. The book is still worth reading, though, just to have the basic key points of hard work and accomplishment-of-everything hammered into your brain. It is also interesting that there are a variety of secondary characteristics that often, but not always, characterize successful entrepreneurs. Most of them make at least a brief appearance in this book. They exercise regularly. They are not fat. They are strong-willed. They are flexible. They get back when up when knocked down. But all these are not additions to the Golden Dyad; they are manifestations of the same underlying character traits that drive the Golden Dyad. Thus, for example, successful entrepreneurs are not usually obese, because obesity is the external evidence of lack of discipline, the same discipline necessary to focus and accomplish.

There are non-trivial costs to executing the Golden Dyad. I missed much of my older children’s very early years, and as I used to, with some exaggeration, bitterly complain to my wife, “I sold my friends for money.” John, similarly, has few amusements; he doesn’t watch Game of Thrones or do politics. He does party quite a bit, still, but his claim, which I have no reason to question, is that partying is business for him. Beyond the Golden Dyad, business approaches can differ wildly, and that is true as between John and me. I am, for business purposes, a solipsist, and my business does not require me to network or party with anyone. Nor do I have any desire to do so. For the most part, I am a ghost, and notoriously hard to actually reach except for the most important customers. You will not find me taking customers out to Colts games. John is in the image and hustle business (or rather, several of them), and that is simply a different type of business. But we are the same, down deep.

Back to the Pope. John prays, as he says several times in this book. I have to admit, I have never prayed about business. It seems greasy, somehow, to ask God to give me money. Why compound my sin of avarice with asking God to participate? That’s not to say I don’t recommend prayer; I just never made a connection between it and business. In my most recent confession (immediately prior to Eastern Orthodox chrismation), I had to cough up my love of money. Oops. Fortunately, my priest didn’t tell me to sell all that I had and give it to the poor. I’m relying on the explicitly approved example of Zacchaeus—he only gave half to the poor.

Still, entrepreneurship is not for everyone, even if you can execute the Golden Dyad and bear the costs. Some people just don’t have the personality for it. For example, most lawyers who start their careers at large law firms (i.e., the cream of the lawyer crop) embody the Golden Dyad. But by self-selected personality, they are mostly risk averse, and trained to only offer analysis and to let others weigh and make the actual decisions. If they can push themselves past those limitations, though very few can, I would put my money on such a lawyer any day as the most likely to succeed. Another debilitating personality trait is internalizing stress. The grind, in John’s word, is extremely stressful—even if you don’t face personal ruin if you fail, which most real entrepreneurs do. So if you have to take Xanax before your business even opens its doors (as a friend of mine did), you will not be a success, and you may end up eating a bullet.

The irony of all this is that all those people on the outside, who cannot or will not live the Golden Dyad, but want what it brings, and exist as wage slaves or, worse, parasites of one kind or another, rarely admit to themselves that their failure to achieve such escape velocity is their own fault. John says, along these lines, speaking of criticism of one of the people he profiles, Kyle Maynard, born with no arms or legs, “It just goes to show you that people will always find a reason to point at you and say you’ve had some sort of advantage.” The reality is that claims of “privilege,” wherever found, in business or any other area, are almost always merely an attempt by the speaker to cover up his own inadequacy. This is true in every walk of life, but most of all in entrepreneurship, where success breeds fierce envy, especially from those who know, deep down, they lack what it takes.

While the road to entrepreneurial success is always through the Golden Dyad, the reasons why entrepreneurs do what they do are not the same, and that also implies that their paths, past a certain point, diverge. Some love the process, the racetrack, the work and the accomplishment; such people often become serial entrepreneurs. Others, like me, are in it purely for the money. Those who are in it for the money may be it in for money itself, as a marker of success; those are the types who, like the fisherman in the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tale, keep asking for more until they are cast back to the poverty of their beginnings. Or they may be like me, in it for the money, for what the money can do.

That is to say, I don’t enjoy the racetrack, and I’d be happy to get off. In fact, I am off, mostly, even though I am still running my business, because I have an outstanding team whom I have given near total independence. But it took ten years to get even a small break from the grind, and twelve to get where I am now, able to spend whole weekends nearly without thinking about the business at all. Certainly, I have to pay some attention, to keep it growing and make sure it doesn’t go off the rails, but past a certain point most businesses have a certain degree of stability. My biggest concerns are macro concerns, with the economy or zombie apocalypses, not immediate business concerns. Those do not have a place on the racetrack.

I can hear you asking, what if you don’t succeed, even if you execute the Golden Dyad? I talk as if success is guaranteed, but that cannot be the case. Certainly, other things intervene—simple fate, inadequate talent in a chosen field, and much more. My strong belief, though, is that as long as you stay away from loser businesses like restaurants, reasonably intelligent people who can execute the Golden Dyad are highly likely, probably greater than eighty percent likely, to be a success—that is, to generate substantial, if not spectacular, wealth. But of the twenty percent, there are two distinct negative outcomes: delayed success, and actual failure.

As to the former, how long can an entrepreneur keep going if success does not appear? Quite a long time, I think. If you once begin to execute the Golden Dyad, in most cases you can keep going forever. And in fact, if you fail, you can often pick yourself up off the ground and keep going. For years, about ten percent of my racetrack was contingency plans, how to ease the creation of a totally new business if my core business failed. Whether your can bear the stress, or your family can bear the stress, of too-long-delayed success, is another question. But for some people, their pepper ship never comes in. Or their failure is so catastrophic as to prevent any resurgence. I don’t have a solution for that; sometimes life isn’t fair.

Beyond individual entrepreneurial success, it is worth mentioning that the Golden Dyad of hard work and ability to accomplish is not just a rarely found personal characteristic. It is also grossly unevenly distributed across cultures, which is why some cultures are economic (and cultural) winners, and most are losers. Ten years ago I spent a week in Shanghai, where I went all over the city. Not once did I see a single person not busily occupied in accomplishing something. Not once. If I went to Cairo, or Mexico City, or Naples, I bet I couldn’t get ten feet without seeing several people (usually men) doing nothing at all. Collectively, such actions have consequences, visible and invisible. A culture that demands, and rewards, excellence, like we used to be, is going places. The converse is also true. Get woke, go broke.

Oh, I have many more thoughts on entrepreneurship. I also have thoughts on what follows from success in entrepreneurship, including why the term “giving back” is odious and stupid. These are the core thoughts, though. And yes, I will answer questions directed to me on this topic, so feel free to ask away!