Last year, I went to the State Fair, and simply sat and watched the people pass by. The vast majority were lower class, and looked it. I tried, for a change, to ignore the externals and imagine myself conversing with individuals with whom, to an outside observer, I have nothing in common. Chris Arnade wrote Dignity to document a similar exercise, though one far more in-depth. He travelled the country, talking to many people from the lower classes, what he calls the “back row.” Then he wrote up what he had learned, and added a great deal by filling the book with pictures, so that the reader can perform the same exercise I did at the State Fair, and ponder respect and the back row in today’s society.

I really wanted to like this book. I agree with much in it. Like me, Arnade doesn’t think a rising GDP per capita is the measure of human flourishing. But what Arnade never asks is where dignity comes from or, for that matter, what it is. As a result, he is unwilling or unable to make distinctions that need to be made, and he refuses to require anything, anything at all, of the back row, even when their behavior is, by choice, utterly degraded. This lack of clear thinking sharply reduces the value of his book.

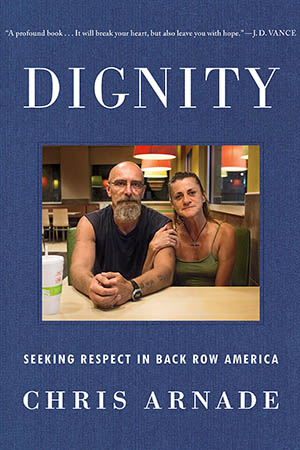

Thus, in a couple whom Arnade spends a lot of time with, where the husband’s only employment is to pimp the wife so they can buy drugs and find a place to stay, both husband and wife stridently claim that they have dignity. And maybe they do, in the eyes of God, and in the sense that no human life is worthless and each should be cherished. But in the eyes of man, their behavior is degraded and wholly unacceptable. The real definition of dignity is the feeling of knowing that one has done the best that one can, with what one has, to fulfil one’s purpose and duty to God and man, from which flows self-respect and the respect of others. Dignity has to be earned by meeting legitimate expectations, not demanded, assigned, or redistributed. Arnade cannot, or cannot bring himself to, distinguish the activities of prostituting oneself for drugs and of working a good manufacturing job to support one’s family. Only one of these things can truly lead to dignity.

The book is far from worthless, however. In a well-run society, everyone should have the opportunity to earn dignity, and Arnade does show how many in the back row are today denied that opportunity. That denial is the result of the world the front-row kids, the worst ruling class ever, have made. The derelictions and cretinisms of that class, however named, have been very well covered in a series of recent books. James Bloodworth’s Hired (where dignity is a major focus). Tucker Carlson’s Ship of Fools. Oren Cass’s The Once and Future Worker. Richard Reeves’s Dream Hoarders. Joan Williams’s White Working Class. Arlie Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land. Angelo Codevilla’s The Ruling Class. And many more. Dignity is best viewed as complementary to those lines of thought, not a groundbreaking study of its own, which it could have been had Arnade been willing to make distinctions among those to whom he talked.

Arnade’s path to alienation from the front row was gradual. He grew up in Florida and left his hometown after high school, seeking the life of the front row: based on the right education and the right jobs. In his taxonomy, the “front-row kids” are perhaps twenty percent of the population, those who follow the new cursus honorum, getting the right college degrees, the right jobs, and the right connections, and end up at the top of today’s society. The back-row kids are the opposite (and there is also an in-between).

The front row is money-centered, yes, but also unmoored from home, or from any place at all, and ignorant of anything that can’t be measured, such as “community, dignity, faith, happiness.” The difference between being front row and back row used to be not as stark. The front row gave up certain comforts, including a sense of home, in exchange for a more cosmopolitan existence; the back row took the opposite deal. But now, the front row have gathered everything to themselves, and left the back row with the dregs. The back row, left without jobs and surrounded by the lure of drugs, and, just as importantly, dealing with the resulting destruction of communities, are “now left living in a banal world of hyper efficient fast-food franchises, strip malls, discount stores, and government buildings with flickering fluorescent lights and dreary-colored walls festooned with rules. They are left with a world where their sense of home and family and community won’t get them anywhere, won’t pay the bills.”

Perhaps to simplify things, Arnade ignores gradations among the back row, and effectively focuses on what is probably the bottom five percent of society, what is better called the underclass. Every society has an underclass, and while in all the places Arnade profiles, it is probably more than five percent, perhaps even more than fifty percent, the underclass is not really synonymous with the back row, which Arnade defines as those unable, in practice, to enter the first rungs of the cursus honorum. Arnade pays more attention, though he does not emphasize, that the back row also has an important geographic component, where it is hard to enter the front row unless you grow up on the coasts or in a handful of big cities. I grew up more back row than front row, even though my father was a university professor at a large midwestern state university, since at no point were the options for entering the front row made clear to me by anybody, and I suspect they were not to my high school classmates, either. Nobody at my large state university told me of usual front-row job options like consulting and finance, and I drifted into law mostly because I got a perfect score on the LSAT, and thus largely by inertia ended up at a front-row law school. Even there, nobody told me anything about what law practice was really like, or the gradations among law firms, or all the knowledge that is critical to a planned journey through the front row. I managed, though, and in my favor, I did not have the J. D. Vance problem of lack of objective sophistication, since I had the book knowledge of front-row behavior. Then I threw it all away to make myself rich from scratch in a back-row job, but that is another story.

Arnade, also from Nowheresville, obtained a doctorate in physics and was a successful Wall Street trader for twenty years, but ultimately found that unsatisfying and also turned his back on his class (at least in his employment; it is not clear if he changed his social circles). Around 2012 Arnade drifted into spending his days in Hunts Point, a physically isolated and very poor part of the Bronx. There he got to know many of the locals, and grew to understand their lives—most of all by the simple expedient of hanging out at the local McDonald’s, social center of every depressed area. He did this for three years; then, seeing that he was getting sucked into the lives of his interlocutors, and that nothing ever changed or improved for them, he went travelling around the country. Portsmouth, Ohio. Gary. Bakersfield. Prestonburg, Kentucky. Milwaukee. Selma. All places where the back row dominates and there is no front row to speak of.

Arnade treats these places as functionally the same, with the exception of racism, of which more later. But these places are not all the same. Yes, they all lack jobs, and that has destroyed these communities; it is, or appears to be, the original sin. Arnade blames globalization and Wall Street for the loss of jobs, the unending lust for profits and efficiency, and he is right, certainly. Like Sam Quinones’s Dreamland, this book spends a lot of time discussing Portsmouth, and I have more than forty years of personal connection there, since my grandparents lived there and I spent every winter and summer vacation there when I was growing up (we did not have money to travel, ever). In Portsmouth, good jobs “were the backbone of the community”; they allowed people to build a family around a stable and well-paying job. The town is now unrecognizable even compared to what it was when I was a child, and then it was already on the downstroke.

In fact, Portsmouth and Selma are not actually the same as Hunts Point and Bakersfield. In the former, the jobs have disappeared and are not coming back; it is difficult to find any gainful employment. In the latter, people could find work nearby, but the people Arnade talks to don’t want that work, or, most of them, to work at all. Hunts Point is part of New York City. There are an infinite number of jobs in New York. The people in Hunts Point just don’t want them; they would rather lead their degraded, derelict lives. In Hunts Point, they tell Arnade “There is no jobs here, buddy. No jobs. Just nothing for nobody to do.” That’s objectively false, but Arnade says nothing except to plead for dignity, which here means mostly not stigmatizing people for being lazy and making degrading choices.

In Portsmouth and Selma, it is more plausible that there simply are no jobs, and there are certainly no good manufacturing jobs at big companies as there once were, but the reader has the distinct suspicion that the Hunts Point attitude is more prevalent than Arnade lets on. I have personal experience with this—I employ a large number of employees in light manufacturing, and it is extremely difficult to find workers who will show up and do the work, which is well paid (starting at twice minimum wage), offers good benefits, and is neither dangerous nor especially grueling. Anecdotally, you hear frequently of employers in places like Portsmouth, machine shops, for example, unable to hire even when offering excellent jobs with free training. I am quite sure, from experience (I have had a lot of direct contact with the back row), that nearly everyone Arnade talks to would not take my jobs if I offered them, or rather, might take them, and then would not show up except when it pleased them to do so. The problem, in other words, is not just that the jobs have disappeared, but also that the work ethic has disappeared.

Why? Is it lack of jobs, or something else? Is that broken families and illegitimate children are now the norm in all these communities (something about which Arnade says not a word) the result of lack of jobs, or the result of something else? How does the ubiquitous consumer mindset, where people work two jobs so they can buy more cheap, disposable Chinese tat to brighten their life for a day or two, figure in? It is instructive to read Charles Murray’s classic 2012 book Coming Apart to get some insight. Using extensive statistics, Murray shows how the “cognitive elite,” his term for the front row, has separated from the lower classes, who have sunk into various forms of dysfunction, with the disappearance of “family, vocation, community and faith.” It is also instructive to read Theodore Dalrymple’s Life at the Bottom, about the British underclass. Dalrymple assigns blame to the spread of nonjudgmentalism, totally absorbed by the underclass, which is in essence the same thing as believing in dignity as lack of stigma. Reading works like these makes clear that it’s not just lack of jobs that has cast the back row down; lack of jobs has instead contributed to a broader decline in moral fiber, that has deeper roots, though the front row is still to blame, as it is for the disappearance of jobs, since it was their deliberate destruction of virtue that is a major cause.

What Arnade won’t say, though, he at least allows one of his conversation partners to say. In Prestonburg, Kentucky, one man says “Parents and grandparents took their kids and grandkids; they don’t do that anymore. We used to be self-sufficient here. People wouldn’t take gifts. We had pride. Self-respect. Then we were flooded with gifts from the government; it took people’s pride and self-respect away. The government and internet hurt our churches, and Walmart coming to town closed every mom-and-pop business. Now people only take pride in drugs.” The problem is that reversing this is not as easy as simply backing up.

Drugs are the downfall of the vast majority of these people, and Arnade spends a lot of time talking about them. He attributes usage to dulling the pain and giving people a moment of joy, which is doubtless true. But he is somewhat credulous, attributing most drug use to “dissociation” resulting from childhood betrayal of trust, reinforced by lack of trust on the street. As always he offers no judgment, and no requirement for any sort of personal responsibility. Wherever precisely the truth lies, the easier availability of drugs that comes with legalization is revealed as yet another social policy that would benefit primarily the front-row kids and harm the back-row kids. The solution isn’t as easy as stricter enforcement, though. There is something to be said for the Indonesian or Singaporean approach, but Arnade isn’t wrong that jobs would help. Again, though, I don’t think it’s mostly the jobs—it’s the web of society and community that is, over time, generated by good jobs, the type that permits a man on his pay alone to support a wife and children, creating strong families, without which no community is possible. That web makes drugs less attractive, an effect beneficially increased by social stigma imposed on drug users.

If, reading Arnade’s stories, you listen closely, two elements keep rustling in the background, whispering to the reader that respect, or even human pity, is not the only necessary reaction to the plight of the people portrayed. The first is that the back row, in Arnade’s telling, firmly rejects help from non-profits and other charitable organizations, non-governmental and governmental. Arnade does not discuss the details of what is offered, but he makes very clear that those he talks to have a fierce aversion to any such help. Their objection is not that they cannot get needed help; rather, it is that “rules and lectures about behavior,” to which help is supposedly tied, are not to their taste. It seems unlikely, though, in today’s obsessively nonjudgmental environment, that there are any such lectures. No doubt bureaucracy is annoying, and as James Bloodworth says, poverty is the thief of time—but all the people Arnade talks to have nothing but time. The reader intuits that Arnade interlocutors have, again, absorbed that any stigma is a great offense; rather than feel stigmatized, or told, even gently, they should consider stopping their vice-ridden habits, they will try their hardest to avoid getting help.

But then, the second element—how do these people find the money to live? Arnade implies that they hustle in various ways, but the reality flashes through. When talking about a prostitute in Hunts Point who came from Oklahoma, and asking her if she wants to go back, she responds that everyone from home is busy. “I got nothing to offer them. What am I gonna be? A social security check that everyone wants.” Bingo. There it is. The government, as far as I can tell, gives money to all the people Arnade profiles, but he never mentions it, except for this one oblique reference, and a second reference that “the welfare office,” like other government and official offices, “are just big buildings that give them nothing but heartache and problems.” What heartache? What problems? We are not told. We are just supposed to accept the choice made to reject help in changing, but to accept cash. No judgment permitted. The reader is left with the conclusion that if cash, or perhaps medicine, is given out, the back row, or the underclass portion of the back row, will eagerly accept it. What they don’t want is help to end their pathologies.

Arnade is on strongest ground when he talks about religion, which for the vast majority of the people he talks to is their sole actionable route to real dignity, via the transcendent. In every place he goes, he visits local churches, attending services as a welcomed guest. He admits to his own hideous scientism and notes that everyone he meets in the Bronx “who was living homeless or battling an addiction held a deep faith.” “The preachers and congregants inside may preach to them, even judge their past decisions, but they don’t look down on them.” He himself becomes no longer an atheist, nor a believer only in the instrumental value of religion, but—something else.

Arnade is on weakest ground when he talks about racism, which is quite a bit. By racism, he means racism against African Americans. (He never quite comes out and says it, but it’s entirely obvious that, like any thinking person, he realizes that the only type of racism that matters or has any historical freight is that against African Americans. Hispanics, for example, claiming historical racism should go pound sand.) No doubt in the twentieth century African Americans were frequently deliberately economically disadvantaged in ways that still echo today, a topic well covered in Richard Rothstein’s fantastic The Color of Law, which Arnade does not cite, but should. Arnade notes that the front row is all about credentials, and African Americans find it hardest to obtain credentials. Affirmative action merely offers a tiny slice of people the ability to reach the front row—on the condition they leave home, “readjust their values, [and] readjust their worldview.”

Among African Americans in the back row, though, it’s pretty evident from the people Arnade talks to that racism as a problem is usually a distant competitor to lack of education and lack of jobs. Among whites and Hispanics in the back row, most are not racist at all. But Arnade can’t just leave it there. He’s a man of the Left, as he likes to remind us, and he keeps talking about the supposed problem of increasing racism among resentful whites. Now, I agree this is a real potential problem—as I frequently say, and am now more frequently saying, white racism channeled by a competent politician is likely to be a winning political strategy come the next big economic downturn, and it’s not going to be pretty. But Arnade never portrays any of his interlocutors as racist at all, and that undercuts his claims, which therefore seemed shoehorned in.

After all this, Arnade is, not surprisingly, angry at the front-row kids, first for causing the problems that the back-row kids face, and second for having no idea about the lives of people outside their bubble, and being contemptuous of them. Arnade is further incensed that the stock front-row response, from Left and Right alike (famously encapsulated in an odious 2016 screed from that dying bastion of loser conservatives, National Review), is that the back-row kids should move to where the jobs are, and that the real problem is that they caused their own social pathologies. As I say, there is some truth to that, and J. D. Vance went into this in some detail in his own memoir of back-row life. All the people Arnade interviews, though, identify very strongly with home; it is the one thing they have left. Moreover, it is expensive to move, and most back-row people lack the networks that allow them to resettle—what networks they have are part of their home. Not to mention that the mere ability to think in this way is mostly a front-row talent. Beyond that, though, no well-run society should hollow itself out by demanding the poor congregate in Megalopolis; it is no way to run a country.

I don’t dislike the front row in the abstract. I dislike today’s front row. Arnade is not a political theorist, but he probably agrees that there has to be a ruling class. We will always have class distinctions, and should. We just need a decent ruling class, and Arnade is right that ours is awful. It is exemplified by the Cambridge student in 2017 who, when asked for money by a homeless person, burned a twenty pound note in front of him. In short, what we need, as between the front row and the back row, is justice. Not social justice—which is, as Paul Rahe said, “a slogan used by those intent on looting.” Rather, justice in the sense of giving to each person what he deserves. There are many classes, each with its own needs, rights, and duties. The front row needs to recognize its duties to the back row, and to the nation as a whole; the back row needs to recognize its duties of self-help wherever possible, and the absolute necessity to reject the modern definition of dignity, and embrace the old definition. In that project the front row needs to lead and assist.

None of this can be solved easily. Smashing the current ruling class would be a good place to start. To do that, you’d need to smash the administrative state, the media, and the universities, rusticating their denizens and permanently stripping them of all influence and power, which is a tall order. You would then need an industrial policy that prioritized American jobs that are not concentrated on the coasts, followed by a general renewal of virtue (probably only possible through religion). As a woman in Cairo, Illinois, says: “But we are good people, smart people, who could show that if we had opportunity. We can be productive, but there is no grocery store, no gas station, no resource center. Nothing is here.” This is it. The goal of the Foundationalist state, based as always on hewing to reality, will be to offer opportunity—not the opportunity to join the front row, which anyway is going to be purged, but opportunity in place. It will also sharply distinguish between the deserving and undeserving poor, offering strong help for the former, and strong correction for the latter. As I say, a tall order, but something has to be done. A degraded proletariat spells trouble, a lesson from history that I think the front row, tripping the light fantastic, with their Teslas and palaces of glass, have forgotten, just as they have forgotten, for the most part, the back row’s very existence. They should read this book.